Fallen Leaders: Earl Van Dorn’s Final Obscurity

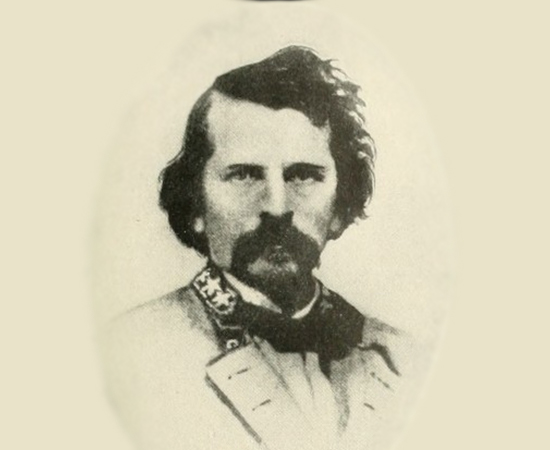

As charismatic as Earl Van Dorn was in life, as a man people flocked to, as someone who personified that old expression “Men wanted to be him, and women wanted to be with him,” his afterlife seems to be a lot lonelier, at least here on this mortal plane.

I recently stopped by his final resting place, Wintergreen Cemetery in Port Gibson, Mississippi. His grave sat well away from all the others in an almost forgotten corner, overshadowed by encroaching shrubs. No sign pointed the way to the interred dignitary for tourists or curious visitors. As he was a leader of men in life, he now seems a pariah in death.

Van Dorn had a checkered military career. He was an inspirational leader of men but a pretty terrible general—a phrase my friend Kris White has used before to describe other officers. It fits Van Dorn. Van Dorn had proven himself a failure when it came to large commands—see Pea Ridge and Corinth—but had proven effective as a cavalry leader, with particular success at Holly Springs in December 1862.

A transfer to central Tennessee proved his eventual ruination. Although married, Van Dorn had a reputation as a womanizer, and while posted in Spring Hill, Tennessee, he carried on an affair with Jesse Helen Kissack Peters. Her jealous husband walked into Van Dorn’s office on May 7, 1863, and shot the philanderer in the back of the head. John B. Jones, a clerk in the Confederate war department in Richmond, summed it up succinctly: “Gen. Van Dorn is dead—being killed by a man whose peace he had ruined.”

(See my May 2021 post for details about my visit to Spring Hill and more on this story. And stay tuned for Matt Atkinson’s symposium presentation on Van Dorn coming to C-SPAN’s “American History TV.”)

Originally buried with his wife’s family in Alabama—and I can only imagine how well that went over, knowing the circumstances of his death—Van Dorn’s body was later disinterred and brought back to his own hometown of Port Gibson, Mississippi. He was buried next to his father.

And there the two remain. Even the sister who directed efforts to bring Van Dorn back to Port Gibson ended up buried somewhere else.

Port Gibson is a smooth 35-minute drive south of Vicksburg best known as the site of the opening battle in Grant’s overland campaign to take the Key City in May 1863. As legend has it—and that’s all it is is legend—Grant called Port Gibson “too beautiful to burn.”

I follow U.S. 61 through bucolic rolling hills, eventually coming into town on a richly tree-lined main thoroughfare. This stretch of Port Gibson is, indeed, beautiful.

From U.S. 61, Greenwood Street toward the south end of town leads back to the cemetery. The street crosses a small bridge, and then bends to the right, although a bulb of pavement bulges off to the left like it can’t decide if it wants to turn into a road or just a pull-off. The driveway to Wintergreen Cemetery opens from there. Detritus and garbage lay scattered along the edge of the bridge and pull-off, but the cemetery itself is free of litter. The grass is badly in need of trimming, though. The spirits have collectively glowered, “Get off my lawn!” to the groundskeeper.

Wintergreen is every stereotypical gothic Halloween graveyard you’ve ever seen. A narrow, eroded ribbon of what might have been blacktop loops through the cemetery, but the headstones seem to begrudge its presence and give the road—or cars on it—little space to move. Tall, old trees draped with Spanish moss tower over the road and canopy the tombstones, which also all seem to crowd each other, vying for space where there is none. Most of the stones are old and impossibly thin as only old marble tombstones can be. The top halves of several have been knocked clean off and then cemented back on. While the broken stones might have been the work of vandals, it’s just as likely they’d been clipped by the bumpers of cars. Headstones cramp the driveway on both sides, and an incautious driver could easily take one out, especially rounding a bend. Similarly, falling branches from the ancient trees might have cracked the headstones.

Where those old trees stand over tight clusters of graves, the headstones have all turned a powdery reddish brown. If the stones were old cars, I’d say they’d all rusted over. It sounds melodramatic to say everything looks covered in dried blood, but it does indeed look like some horrible scene was acted out in the not-too-distant past, leaving its stain all across the graveyard. I’m so creeped out I don’t even want to take pictures. I want to find Earl Van Dorn and get out. The place feels malevolent—and that’s coming from a guy who doesn’t get spooked in cemeteries at all.

Perpendicular to the north side of the cemetery, several lines of neat, white gravestones jut from the ground like rows of teeth. These were Confederate dead killed at the battle of Port Gibson in May of 1863 and elsewhere. I see stones for War of 1812 veterans, too.

It takes a while to find Van Dorn. He and his father, a former judge, are buried side by side but are otherwise alone along the cemetery’s north edge, only about 50 yards from the cemetery’s main entrance. Thick foliage creates a border that may or may obscure a wrought-iron fence; I saw one when I drove into the cemetery but can’t tell if it encloses the entire property.

It takes a while to find Van Dorn. He and his father, a former judge, are buried side by side but are otherwise alone along the cemetery’s north edge, only about 50 yards from the cemetery’s main entrance. Thick foliage creates a border that may or may obscure a wrought-iron fence; I saw one when I drove into the cemetery but can’t tell if it encloses the entire property.

By the Van Dorns’ graves, the grass has given way to thin weeds. Their stones are powdered with the rust color. Perhaps some windstorm once blew up the red Yazoo clay into a duststorm that coated the stones. Perhaps something has leached out onto them from the overhanging plants. Pictures online from decades ago show white, clean stones and a thriving, happy lawn.

Van Dorn gets two headstones: a stout monument erected by his family to match his father’s and one erected by a Confederate heritage group that emulates stones found for U.S. veterans in national cemeteries. The smaller stone leans woozily akimbo, although the online photos show it once stood at crisp attention.

Under other circumstances, I might describe this as a quiet, secluded peaceful spot—but there’s nothing peaceful about this cemetery, at least not this morning, which is warm and sunny and otherwise quite pleasant. The cemetery resents the weather. Although I will later regret not taking photos, I am glad to make my exit.

Van Dorn may live on in sordid Civil War infamy, but he rests—if he rests—in lonely obscurity, a “ruined peace” all its own.

Thanks for taking us along on your visit!,

You’re welcome. More to come, here and on the ECW YouTube page!

Matt Atkinson’s talk on Earl van Dorn at the ECW Conference was an absolute classic—funny, interesting and dynamic! One of the most entertaining talks I’ve heard, on any subject, anywhere!

We’re looking forward to its C-SPAN premier. We’ll keep everyone posted once we know it’s coming.

As a cemetery tour guide, this was a particularly good post.

Thanks!

An enjoyable read. YOu should have done a video on your visit.

I predict a Civil War Trust Park Day visit to Port Gibson with a rake, D-2 Stone cleaner, weed whacked and gloves.

Nobody interprets historic sex, scandal, & drama like Matt Atkinson (at the ECW Symposium). It makes me want to sit in on one of his Dan Sickles talks. I’ve also personally witnessed Matt Atkinson resurrect the dead more than once after a long list of speakers at a Civil War conference.

So evocative that it makes me want to visit!

Great information on such a fascinating Civil War character. Another good source of information on Van Dorn is https://legendofvandorn.com.

The article must have set Van Dorn fans into action. There is a brand new stone at the site “… in appreciation of this man’s efforts to establish southern independence” complete with Confederate battle flag. Placed in 2022.

Do you have a photograph of the new stone?

I visited the “Soldiers Rest” section of Wintergreen last month, for the first time, after trying to puzzle out the geography of the battle site. I had been very spoiled by the signage and information available at Vicksburg, and found it difficult to picture the layout at PG (and also at Chickasaw Bayou). Didn’t spend significant time in fruitlessly looking for Van Dorn, but really expected to see a more substantial monument.