The Most Devastating Confederate Attack?

Chancellorsville is often seen as one of the Army of Northern Virginia’s greatest attacks, achieving a victory against overwhelming odds, yet I would argue that rivaling that is the one launched on the third day of fighting at Second Manassas. Although not involving as many troops, the magnitude of the attack violently and abruptly altered the course of the battle, ultimately ensuring a Confederate victory on the site of the previous battle a year earlier.

At Chancellorsville Jackson massed about 30,000 against a Union corps of about 8,000, yet at Second Manassas Longstreet put five divisions, about 25,000 men, against a lone brigade of perhaps 1,000 troops.

Two wings, led by Generals Stonewall Jackson and James Longstreet, comprised the Confederate army at the time. Jackson’s command had arrived in the area first, destroying the Union supply base at Manassas junction and then taking a defensive position along a railroad cut north of the battlefield of a year before. Union troops of the Army of Virginia under General John Pope concentrated on Manassas to attack them. General Longstreet’s wing was on the way, as were reinforcements for Pope from the Army of the Potomac.

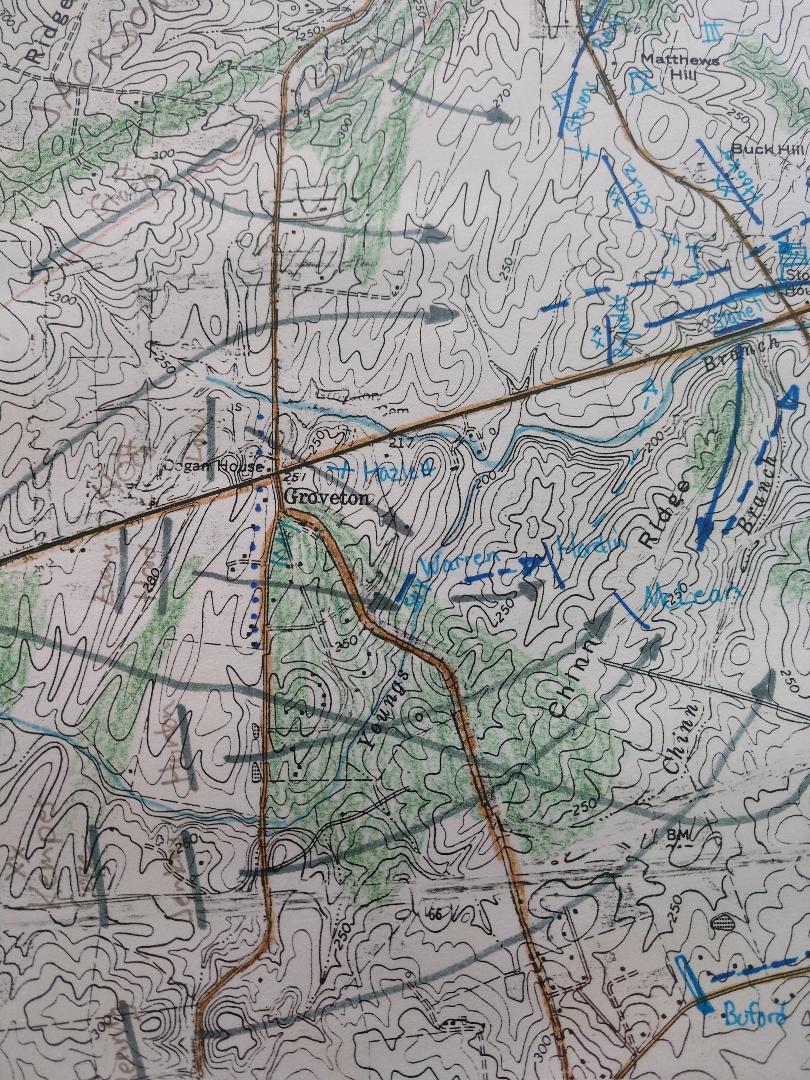

For two days, August 28th and 29th, the Union forces assaulted Jackson’s men at a railroad cut, a ready-made defensive position. There had been intense fighting and even some temporary breakthroughs on the 29th, but Union troops could not exploit any advantages they gained. In the meantime Longstreet’s divisions arrived and deployed to the right (west and south) of Jackson’s position, on the Union army’s left flank.

Their presence did not go unnoticed. Union cavalry under General John Buford reported it to General Irvin J. McDowell, yet McDowell didn’t pass it on to Pope. All of Pope’s orders and plans were based on the assumption that Longstreet’s command was farther away and could not reach the area in time to assist Jackson.

On the morning of August 29th Pope had sent instructions to General Fitz John Porter, commanding the Army of the Potomac’s Fifth Corps, to move from Manassas Junction to Gainesville, which would bring him to the Union army’s left and allow Pope to strike at Jackson’s flank or rear. Orders also went to other commands to attack Jackson and pin him in place. These events ultimately resulted in the controversy surrounding Porter’s actions and his eventual removal, but that is not part of our discussion here.

At Groveton on the Union army’s left, General John Reynold’s division of three brigades skirmish with General John B. Hood’s newly arrived division. Reynolds sent several messages to Pope but the army commander did not believe it. One messenger was greeted by Pope saying, “You are excited young man, the people you see are General Porter’s command.” He never considered the possibility that Longstreet’s men had arrived and his own reinforcements under Porter could be delayed.

On the morning of August 30th Longstreet’s wing was in position astride the Union’s vulnerable left flank. Reynolds continued to pass on information all morning to headquarters, as did the 4th New York Cavalry. These reports noted that Confederates extended beyond the Union left. At mid-day 8,000 Union troops south of the Warrenton Pike faced about 25,000 Confederates.

Heavy fighting took place along the Jackson’s line that day at the railroad cut, with several Union assaults beaten back. After their last attack, Longstreet launched his assault around 4 pm.

That afternoon General Irvin J. McDowell moved Reynold’s division to support troops near the railroad cut, leaving Charles Hazlettt’s Battery D 5th U.S. Artillery and G.K. Warren’s brigade of two regiments, the 5th and 10th New York. Only two other brigades were in the rear and in supporting distance of Warren. Now 25,000 Confederates faced 1,000 Union troops.

When Longstreet’s attack went forward, an entire division (Hood’s) slammed into the two isolated Union regiments. The 10th New York was overwhelmed within minutes, its historian writing that, “The attack was so sudden that he deployed companies of the Tenth barely had time to discharge their pieces once before the Rebels were upon them.” It was a much more lopsided situation than that faced by the 11th Corps at Chancellorsville.

The 5th New York held their fire to allow the 10th to fall back but they crashed into the 5th creating confusion. The Texas brigade now surrounded them on three sides. In the first two minutes the 5th New York lost over 100 men. It was all over in about 40 minutes, with the 5th losing its state flag and 140 men. The 5th New York at Manassas has the highest number killed (125 men) for any regiment in a Civil War battle. Only 60 men survived of the 560 who stood in line. The Confederates moved on to engage the other Union brigades to the east at Chinn Ridge, eventually pushing up to Sudley Road and the base of Henry House Hill, where darkness ended the fighting. The Confederates inflicted losses of 21 percent on the Union army at Second Manassas, suffering a loss of 16 percent. At Chancellorsville Lee’s army inflicted 15 percent losses on the Federals, suffering 25 percent.

Why has this tremendous flank attack not been as recognized as other great attacks like Jackson’s at Chancellorsville, Pickett’s Charge, or others? Perhaps one reason is that events moved quickly. Within days the Army of Northern Virginia was in Maryland, and week later Antietam was fought. That battle, with its massive casualties and political ramifications overshadowed Second Manassas. The northern and southern public barely had time to digest the results of Manassas before the next campaign was in full swing.

Perhaps another reason is the massive shake up in the Union army. John Pope was widely disliked and dismissed from command three days later. The Army of Virginia was broken up and its three corps were renumbered became absorbed by the Army of the Potomac. Amid all that disruption, details of the battle were lost in the shuffle.

Another likely reason is that the controversy surrounding Fitz John Porter and his movements came out of the battle and has consumed the attention of the public at the time, and historians, ever since.

Also at Chancellorsville, Jackson was killed at the height of success. He had led a risky flank march and launched a successful attack. No such ironic tragedy accompanied Longstreet or any other Confederate commander at Second Manassas.

Finally, the devastating attack at Manassas was due more to poor Union tactics than Confederate skill. Perhaps a combination of these factors clouds our view of this large and successful attack.

When I first saw the subject line, I actually thought it meant “devastating failure” for the Confederates! And my mind instantly drifted to far-off Franklin, TN…

Excellent points, Bert. I’ve always argued Second Manassas was Lee’s greatest victory, not Chancellorsville (though both are pretty good victories for Lee).

Agreed 100%, Kevin

The Federal soldiers at Fort Pillow in April 1864; the citizens of Lawrence, Kansas in August 1863; and the mostly civilian passengers of the express Hannibal & St. Joseph intentionally derailed into a ravine in September 1861 would likely disagree with the above title of “most devastating Confederate attack.” However, if the Western Theatre is discounted, and focus is restricted to the ANV, then the assessment is probably correct.

Mike, you are right, for Shiloh and Stones River were certainly devastating, at least initially.

Bert,

I agree with your overall argument, but I have a few tactical corrections if you don’t mind. You place too much emphasis on Warren’s little brigade and seem to gloss over the combat on Chinn Ridge and the fight for Henry Hill. Longstreet’s assault did not target Warren’s tiny brigade. Henry Hill and the intersection of the Sudley Road and the Warrenton Turnpike were the ultimate goals. In reality, only the Texas Brigade confronted Warren’s brigade. In terms of numbers, it was a pretty even match. However, Warren’s boys were surprised and flanked.

Longstreet eventually would confront nearly half of Pope’s army on the various ridges between the marching off point and Henry Hill. All told, about six separate US brigades would fight Longstreet in the vicinity of Chinn Ridge, where the Union brigades suffered about 2200 casualties in 45 minutes of some of the most intense combat of the war (Confederates would suffer another 2500 casualties on Chinn Ridge alone). All told, about 5000 men were killed or wounded on Chinn Ridge.

Moreover, elements of at least nine other US brigades would defend the Sudley Road and Henry Hill from Longstreet during the final phase of the battle.

Longstreet would suffer 4300 casualties in three hours of fighting, while Jackson, fighting on the defense, would suffer 4000 casualties in three days.

Lastly, while we are on the topic of devastating Confederate assaults, don’t forget about Lee’s final assault at Gaines’s Mill, which included at least 16 brigades and between 35,000 and 40,000 soldiers. This might be the largest infantry attack of the entire war.

You’re right, Todd…. Gaines’ Mill was definitely Lee’s largest attack (and first victory as army commander) and at Second Manassas there was major fighting at Chinn Ridge and Henry Hill. The later parts of the battle that day at Manassas are too often overlooked, they are important. My main point was that an entire Confederate wing was poised to strike on a weak Union flank. As you said, the subsequent fighting evened the odds and reduced the scale of the disaster.

Cleburne’s Cannae! The Battle of Richmond in 1862.

And Longstreet largely accompanied all this by himself. Jackson failed to expeditiously join in the assault taking place right in front of him.

Exactly. Pope survived largely intact because Stonewall failed to join in on exploiting what Longstreet had accomplished.

Bert, solid description, but I would quibble as to whether Second Manassas was Lee’s greatest victory, in great part because Pope’s many strategic mistakes and McDowell’s several tactical mistakes made it into more of an abject Union defeat than a Confederate victory. As you rightly state at the end of the article, “the devastating attack at Manassas was due more to poor Union tactics than Confederate skill.”

Speaking of abject defeats and Longstreet, was it karma that at both Second Manassas and Chickamauga that just as he began a major assault, the Union (Rosecrans at Chickamauga and McDowell at Manassas) pulled troops out of the line right in front of him?

Good points.

Alan T Nolan, years ago, made the point in “Lee Considered” that Chancellorsville, particularly the day after Jackson fell, was too costly, diminishing the victory. 2nd Manassass may also not have been appreciated in its totality since Longstreet commanded the devastating attack, a Georgian not a Virginian.