Civil War History & the Dallas Museum of Art: The Icebergs

(A few weeks ago I had the opportunity to visit the Dallas Museum of Art in Texas. While wandering through the galleries, I kept finding interesting pieces of art with ties to the Civil War. Some pieces were created or displayed during the war years, others have ties to the war because of the artist or subject. Hopefully, the short series this week with photos and my cultural research notes will be informative as we try to understand the art that was viewed or inspired by 1860’s…)

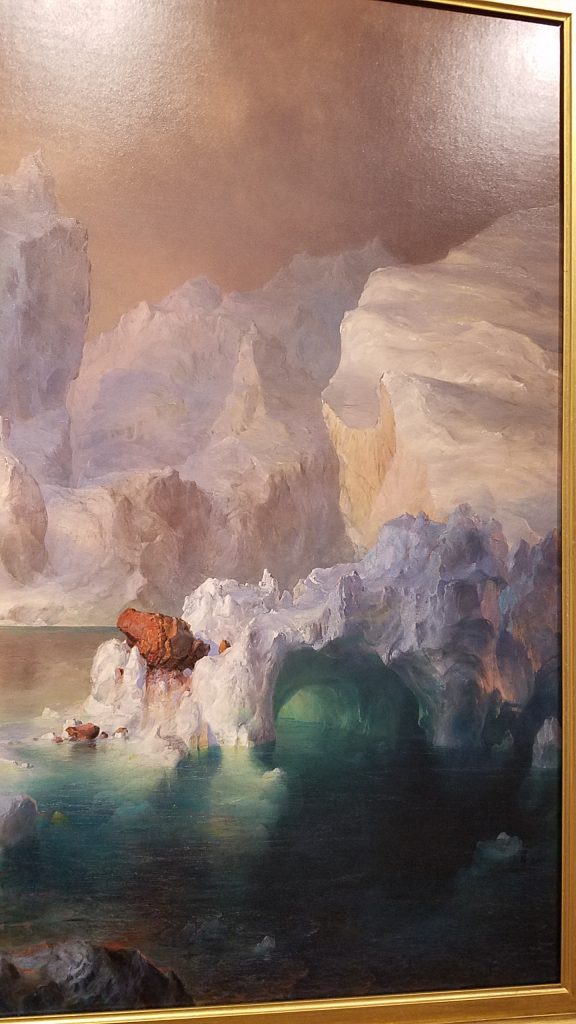

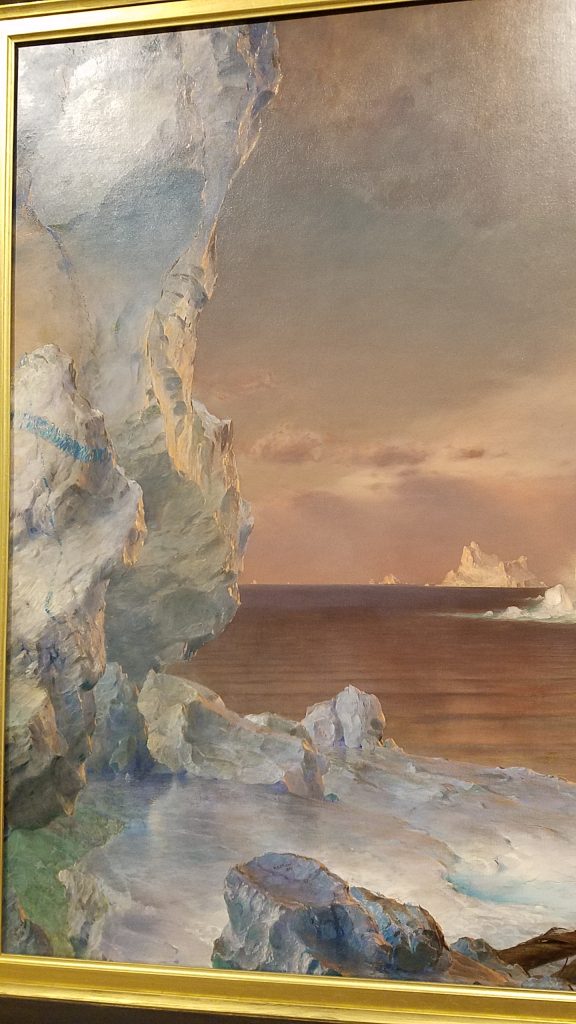

In 1861, Frederic Edwin Church displayed his painting “The Icebergs” or the “Arctic View” in New York City. The large image measures 64.5 inches by 112.5 inches and covers a large wall in the American Art Gallery. When it was first created, the piece capstoned the recent monthlong trip that Church had made into the North Atlantic.

On March 29, 1861, The New York Times published a review of the painting and likely many of the art-appreciators of the city who would be in uniform within a few weeks went to admire the work. The newspaper review reads in part:

We may as well premise, fairly and squarely, that we consider this Arctic scene a first-class painting. It could hardly fail to be attractive,—the motive being given even in the hands of an artist of less ability,—for there is something singularly inviting to all brothers of the easel in ice and snow views. They strike the most common-place observer as suggesting subjects for copy. We believe that the very first independent figure of climate to be found in poetry is the strange mention of the treasures of the snow, and hail, and the frozen deep, in the Book of Job, while the first independent landscapes, as distinguished from old conventional backgrounds… But apart from this natural fascination of subject, the “Arctic View” is admirable from so many points of strictest criticism, and indicates such an exhaustive study of scientific truths as applied to Art, that we may well despair of giving a fully coordinate resume of the whole.

We are struck in the composition at the first glance, by its harmony, with the sentiment of the picture. It is that of intense solitude in the clear frozen North—nature in her utter loneliness—no wild bird or stunted shrub, or ragged relic of aught that ever grew, meets the eye to suggest life. White bergs rise mountain high around an arm of the sea, which vanishes in a darkly-ending fiord, in fine perspective to the left. A mountain with a gracefully sloping glacier, on which plays the most exquisitely treated atmospheric tints, and just such dim suggestions of prismatic light as gleam over all evening snow-fields, forms the middle distance. A road-like base, studded with ice lumps, cheats the eye in its mirage-like effect into imagining town and towers—an effect which many a traveler in frozen wastes will recall with a smile. In the front ground the sea sweeps toward the shore with as gentle a ripple as though it played in warm Southern climes, —an effect which, as here executed in beautiful lines, is singularly graceful. But all is deathly cold. The invisible spirits of the North—the Witch of Mont Blac and the Vilas of Russia may be flitting unseen around, but to the eye of man there is only utter desolation amid all this wondrous beauty. The spectator seems to have discovered a new realm, and repeats, with the Ancient Mariner,

“We were the first that ever burst

Into that silent sea.”

To the right rises masses of ice—blue islands in a blue sea; amid them a turquoise arch over a sapphire current,—but all is ice and the fearful silence of intensest cold. It is not the burning sulpher blue which the sea wears in the warm Mediterranean, and sends up in mad light like the chemical fires of a theatre into the Grottona Azzura of Capri. It is another light and another life here; but always real and always beautiful. Above these, again, rise broken white walls, showing with wonderful truth the gradation of color—tawny above purple—as we see them in sunsets, and as we find them in the prism—the warm tints succeeding the cold. In this accurate collection of color, Mr. Church manifests a conscientiousness which some of the first painters living would do well to imitate. We see in these effects the results of the careful observation of one who has sailed for long days and Aurora-lighted nights among iceberg seas, noting in every way the marvels by which he was surrounded. The observer may be interested to know that a puzzling blue vein which he will observe in a white ice mass to the left, and which seems strange and ribbon-like, was the result of a literal observation, as all all the more peculiar effects.

We might write for hours of the subtle aerial lights which play over the ice-rock and sea in this picture, and of the innumerable watery colors which blend with them from below; but observation must supply the place of word-painting. Let us conclude by assuring the reader that the ”Arctic View” is one of those triumphs of truthfulness and study, subordinated to a wonderful appreciation of the Beautiful, such as could only be effect by a really great artist.[i]

Icebergs actually appear in eastern newspapers rather frequently, and not just in painting reviews. Ships making the transatlantic crossing or other journeys into the far northern waters reported how many icebergs they saw, and those details got printed in the papers.

In addition to the painting and newspaper notices, another iceberg story made the rounds of many American newspapers—North and South—in the summer of 1861. The Charleston Mercury reported it with the headline “Artillery Experiments Upon an Iceberg.”

The British steam frigate Mersey had been sailing Halifax and discovered some icebergs off the Newfoundland coast. Captain H. Caldwell “thought it would be interesting to experiment on them with rifled cannon.” At a distance of four and half miles, his crew fired an Armstrong shell at a particular iceberg with dramatic effect. Having so much fun with their scientific military study, the captain and crew started firing off “hollo shot, percussion, and shrapnel, and time fuze shell, etc. —all tending to exhibit one feature in modern warfare at sea, viz: the extreme probability of every vessel being in flames soon after she is engaged.”[ii]

Whether they were seen as beautiful scenes for art, a danger to maritime routes, or a fine opportunity for target practice, icebergs were a subject of interest in 1861 as evidenced by the artist display and newspaper notices of the era. Perhaps looking at artwork like “The Icebergs/Arctic View” and reading the descriptions of the era allows us to gain a better appreciation of the art and culture that was part of upper-class metropolis life on the eve of the Civil War.

Sources:

[i] The New York Times, March 29, 1861, Page 4 “Mr. Church’s View of the Arctic Regions” (Accessed via Newspapers.com)

[ii] The Charleston Mercury, July 8, 1861, Page 1 “Artillery Experiments upon an Iceberg” (Accessed via Newspapers.com)

Fascinating post, as usual. The verbal logorrhea that seemed to infect so much of that era is never on better display! Hey, it’s an iceberg.. it’s big… it’s cold… it’s white… it’s allegorical…it has a taste for White Star Liners?

Excellent post from Sarah as usual. The verbal logorrhea that infected so much of the writing of the era is never better on display. It’s an iceberg…not an allegory! It’s large…and off-white…and cold….and has a taste for White Star Ocean Liners.

That’s definitely the mast of a ship down across the ice. I LOVE that painting.