Under Fire: “Seemed to Forget that He Was an Officer, and Gave No Commands Whatever”

When the 6th Pennsylvania Reserves formed in the spring of 1861, its men and officers elected William W. Ricketts as its colonel. The 24-year-old was a solid choice; he had attended West Point and though he hadn’t graduated, opting for medical college instead, Ricketts “possessed a most decided military genius,” a contemporary described. “He had a quick perception, and a facility in handling and commanding troops remarkable in one so young.” As the 6th Reserves deployed to Washington, D.C., it seemed they were in good shape and ready for combat.[1]

Except, on the day that was to be their baptism of fire, Ricketts was confined to his tent, sick with some form of disease that proved all too common during the Civil War. In his place, the 6th would be led by its second-in-command, Lt. Col. William Penrose. A well-respected lawyer, Penrose lacked even the most rudimentary military training that his colonel possessed. The question then presented itself: how would Penrose and the 6th fare when the bullets started flying?

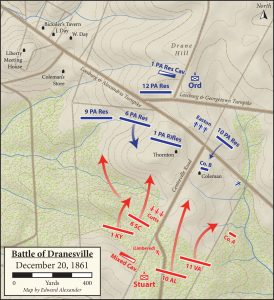

Alongside the other regiments of Brig. Gen. Edward Ord’s brigade of Pennsylvania Reserves, the 6th marched towards the town of Dranesville on December 20, 1861. Their objective was to gather large amounts of forage and to ensure the well-being of Unionists in the area, subjected to forays by Confederate forces nearby. The march to Dranesville from their camps near Langley, just down the road, went smoothly and the soldiers spent some of the time singing that they would hang Jeff Davis from a sour apple tree.

Near noon, the Federal column approached Dranesville and flanking companies from nearby regiments moved to secure the woods south of the town. The soldiers of the 6th Reserves “halted to rest ourselves as we were somewhat tired from the long march and part of it had been made in double quick time,” a member of the regiment wrote later.[2]

They would not have long to rest, however, before the crackle of musketry stirred them to action. Coming from the south was a Confederate column of infantry, artillery, and cavalry led by Brig. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. Unaware of each other’s presence until just moments before contact, the two sides’ skirmishers began to pop rounds off. The Federal skirmishers quickly scampered to rejoin their parent regiments.

Deploying his own artillery on a hill outside of town, Edward Ord sent his infantry forward to secure the intersection of the Centreville Road and the Leesburg & Alexandria Turnpike. The 6th Reserves were ordered into line, with the 1st Pennsylvania Rifles (the Bucktails) to their left and the 9th Pennsylvania Reserves to their right. It was here that the lawyer-turned-officer Penrose would need to lead for the first time.

Penrose, born in 1825, hailed from Carlisle. He had graduated from Dickinson College, and soon after joined the bar. He “rapidly secured reputation and practice, and soon became a leader at a Bar celebrated for its learning and ability.” But now, as the fighting began in the crisp afternoon, Penrose would need to put aside thoughts of legal matters and instead put his attention into the proper way to get a regiment into line of battle and subsequently opening fire.[3]

Except Penrose did none of those things. Being shot at for the first time in his life, he froze in place. One of the 6th Reserves’ soldiers wrote later, “Our Lt. Col., who had taken command thus far, seemed to forget that he was an officer, and gave no commands whatever.” As Penrose hesitated, the regiment’s adjutant, Henry McKean, took charge and “told us to fix bayonets and load our pieces, then about face, double quick march.”[4] Once the 6th was deployed, one of its officers wrote his parents that “We was ordered to lye down upon our faces which we did.”[5]

Seeing the situation unfold in front of him, Brig. Gen. Ord rode up to support the regiment. He directed Col. Thomas Kane, from the Bucktails next to the 6th, to personally help the regiment as well. Twenty-five years later, a veteran from the 6th remembered Ord’s presence on the battlefield, “I can never forget his first command to us in that our first experience in battle.”[6] Once Adjutant McKean took charge of the regiment and stabilized the line, “We soon reached the woods and then came the tug of war,” a 6th Reserves soldier recollected.[7] Musketry crackled and popped along the lines, and canister from the competing batteries slashed through the soldiers.

After about an hour and a half of fighting, Ord’s Pennsylvanians gained the upper hand of the battle. Having suffered heavy casualties, the Confederates retreated in the direction they came, leaving the debris of battle behind. The battle of Dranesville, one of the first Federal victories of the war, was over. In their first test of combat, the 6th Pennsylvania Reserves suffered 16 casualties.

Returning to camp, the Pennsylvanians took stock of what had occurred, including their lieutenant colonel freezing during the battle. The day after the battle, Penrose wrote his official report of the battle. Clocking in at a total of 103 words, Penrose’s report is sparse on the details, though he credits the regiment and says, “The conduct of the troops under my command was all that could be desired, officers and men generally behaving with great coolness and bravery.” That same day, citing poor health himself, William Penrose resigned from the army and returned to Carlisle.[8] He resumed his lawyerly duties and was a well-respected member of the community until his death in 1872.

This quick article is not meant to be an indictment of Penrose’s actions at Dranesville. Rather, Penrose is just one example of many civilians-turned-soldiers who found themselves dropped in over their heads as the reality of war crashed around them. As this whole series of first experiences under fire has shown, soldiers and officers reacted differently in every situation. What happened at Dranesville with the 6th Pennsylvania Reserves also points to the importance of junior officers like Adjutant Henry McKean, who was able to step in and lead the regiment safely through their baptismal fire. Edward Ord also recognized what was happening with the 6th and personally took steps to ensure the stability of the regiment and his brigade as a whole. The quick thinking of officers, from the high level of a brigadier general to the lower rank of adjutant, ensured the Federal battle line never buckled at Dranesville and played a large role in the victory there.

With their first experiences under fire, the 6th Pennsylvania Reserves would serve for three more years and become one of the most experienced regiments in the entire United States Army during the Civil War. Colonel William Ricketts, though, never commanded the regiment in battle. Resigning his commission due to his lingering illnesses, he died in August 1862.

______________________________________________________________

[1] J.R. Sypher, History of the Pennsylvania Reserve Corps (Lancaster: Elias Barr & Co., 1865), 318.

[2] Honesdale Democrat, January 9, 1862.

[3] Josiah Granville Leach, History of the Penrose family of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: D. Biddle, 1903), 103.

[4] Honesdale Democrat, Jan. 9, 1862.

[5] Benjamin Ashenfelter Letter Dec. 31, 1861, Harrisburg Civil War Round Table Collection, United States Army Heritage and Education Center.

[6] William Burgess Letter, Aug. 24, 1886 Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Special Collections.

[7] Honesdale Democrat, Jan. 9, 1862.

[8] The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 128 volumes), Series I., Vol. 5, 482; Samuel P. Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-65: Volume 1 (Harrisburg: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869), 701.

Great article.