Monuments Moved at Gettysburg?: The 15th, 19th, and 20th Massachusetts Infantry

By the end of 1863, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association began to preserve the sacred soil of the Gettysburg battlefield. As time passed, veterans returned to the field in order to dedicate monuments to permanently tell their stories. Some of the first monuments around the Angle are for Massachusetts regiments that advanced to the copse of trees near the Angle to help contain Confederate breakthroughs during Pickett’s Charge on July 3. Specifically, the 15th, 19th, and 20th Massachusetts Infantry Regiments staked a claim on the memory of the battle by placing their monuments directly on the south end of the copse. However, visitors who have seen the modern landscape may immediately notice this historic image does not look the same today, and that the monuments are no longer in their original context. What happened, and why were their monuments moved?

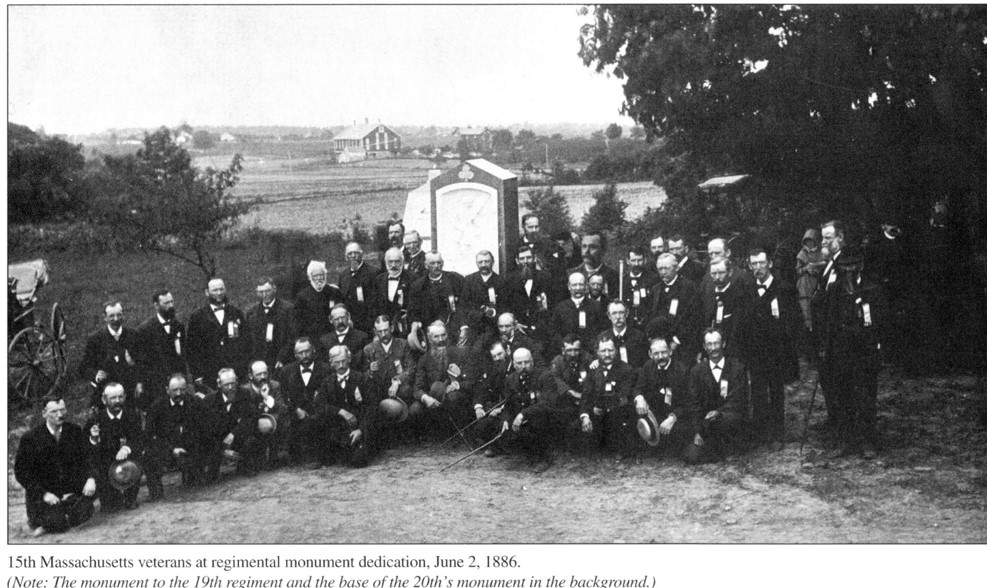

In October 1883, Massachusetts had designated funds to mark the position of its regiments in Gettysburg with iron tablets and markers, so Bay Staters descended upon the battlefield. Representatives from the 15th, 19th, and 20th travelled to the High Water Mark. Soon, small Massachusetts markers popped up around the field. In 1884, more funds were designated for proper monuments, and the regiments began the design process. In 1885 and 1886, the proper granite monuments began to appear in their locations, dedicated with much fanfare from the veterans. The three monuments were placed beside the copse of trees, where they had bravely advanced to repulse the foe.

The 19th Massachusetts Monument, topped with a granite knapsack, proudly proclaimed “THE 19TH REG’T MASS VOL INFTY… STOOD HERE ON THE AFTERNOON OF JULY 3RD 1863.” Following the dedication of the 19th, a speaker said, “On this field the old Bay State’s best blood was shed, and here today by the silent granite and sculptured marble does she honor their devotion.” The monuments would be “perpetual memorials of [the state’s] gratitude and affection” and that future generations would draw “inspiration from the memories of the past.”

At the dedication to the 15th Massachusetts’ monument in 1886, a veteran said the monument “tells of bravery and valor, but it tells of more than these, for it tells of duty and patriotism, and it summons all who look upon it hereafter to answer their call.” Handing these monuments over to the GBMA, these veterans were proud of their service, and loved devoutly their markers, placing them directly in the midst of the action and showing their movement into the fray. The 20th Massachusetts monument, initially devoid of its puddingstone boulder, was dedicated that same year. Receiving the 15th’s monument, the secretary of the GBMA spoke words that would soon seem to be devoid of meaning to these veterans: “The Memorial Association cordially congratulates and thanks you for these beautiful additions to the many historic memorials erected on this field. We promise you that we will carefully watch and guard them, that they may be perpetual memorials to the heroism, courage, sacrifices, and patriotism of the gallant Fifteenth Massachusetts Volunteers and their knightly commander.” However, as the juxtaposition of the historic and modern images depicts, the monuments are not in the same place as they were in the 1880s.

By the end of that decade, historian John Bachelder’s campaign to focus the memory of the battle on the Angle and the High Water Mark has been pretty successful. Plus, Paul Philippoteaux began the grand Gettysburg Cyclorama in 1882, cementing the area in popular memory. It is now a popular place for visitors AND for monuments. The issue is, after examining maps of the battle the GBMA see that dozens of units advanced to that small area. At that time, there were veterans still alive to explain the movements to visitors, but there were concerns that an area crowded with that many markers would be confusing for visitors. After all, one of the goals of the Association was “to secure accurate historical designations of the field so that the visitor can intelligently study it.”

At the December 1887 meeting of the GBMA, the “line of battle” rule was adopted. Now, a unit wishing to place a monument would have to do it upon a regiments line of battle position, that is, a position assigned to the unit before combat began. However, smaller markers could potentially be approved to mark advanced or secondary positions. Specifically, the rule declared, “They must be on the line of battle held by the brigade unless the regiment was detached, and if possible the right and left flanks of the battery must be marked with stones not less than two feet in height.” This poses a potential issue for the Massachusetts monuments, as they were placed marking advanced positions near the copse rather than their line of battle positions that were nearby, but elsewhere.

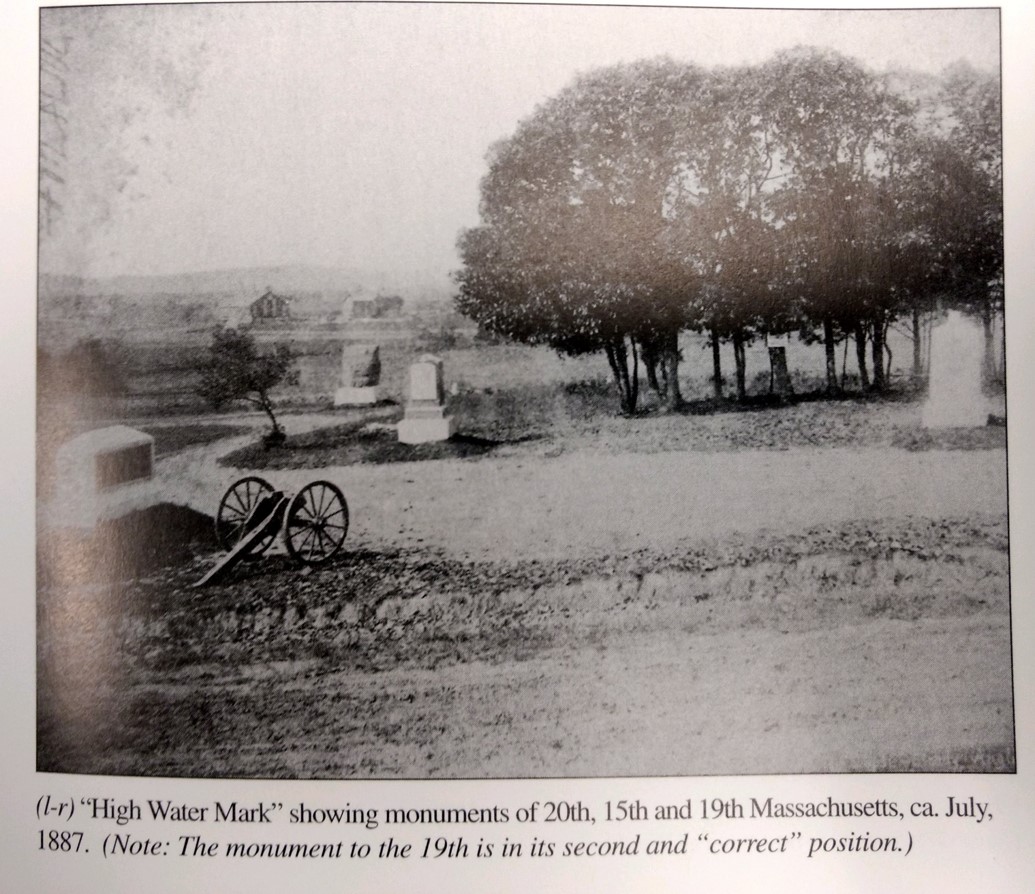

The 19th Massachusetts monument was moved slightly within a year of its dedication. It was fairly minor adjustment, moving it from south of the copse, between the other two, to a new spot directly east of the copse. This is now the place where the High Water Mark memorial now stands. At a similar time, the monument and guns to Andrew Cowan’s 1st New York Independent Battery were placed, awkwardly pointed directly at the 15th Massachusetts monument.

In July 1888, veterans of the 72nd Pennsylvania Infantry approached the GBMA, and, citing the Massachusetts monuments, stated they wanted their monument at their advanced position by the stone wall. The Association rejected the proposal, instead offering a site to the east side of Hancock Ave, 94 yards away, and an advanced marker at the wall. The 72nd had hoped the precedent of the Massachusetts monuments would allow them to place their own in an advance location, but instead it formed the impetus for the GBMA to order the movement of the monuments to the 15th, 19th, and 20th Massachusetts. That same month, Bachelder wrote the 20th Massachusetts that they were “contemplating” moving them, and in September the Association passed a resolution instructing the movement of the monuments to their respective line of battle positions.

The resolution became public, and veterans reacted with anger. In many cases, this was the first time the possibility of moving them had been told to them. The most vocal anger came from Charles Devens, former commander of the 15th Massachusetts. He stated the monuments were “on the exact place occupied by the Regt at the decisive struggle which closed the great battle of Gettysburg with victory” and that moving them would rob the men “of their just claim to honor and renown.” Devens even threatened to use “all honorable means” to keep the monuments there. After all, the Massachusetts men had followed the rules and gotten their monuments approved by the GBMA to begin with, why should they be punished now that the rules changed afterwards?

The Association responded, stating that they could not allow the Massachusetts markers to remain, as they had been accused of favoritism. Vice President Charles Buehler argued “that the marking of the field to suit the wishes of individual organizations to indicate special movements would lead to inextricable confusion and then make the historical features of the struggle unintelligible.” The letter even mentioned the 72nd specifically: “Indeed one Regt, the 72nd Penna, having made claim to a position which would not be historically correct, upon being notified that their claim could not be allowed, have gone even to the length of instituting suit against the Association, to compel us to accede to their demand and one reason governing them they say is that we have allowed Massachusetts Regts privileges desired to them.” Indeed, the Pennsylvanians did go to court (and it was quite the court case) in an attempt to force the association to accept the placement of the monument in an advance position rather than the line of battle position on the east side of Hancock Avenue.

In communications with Massachusetts veterans, the GBMA had been purposefully vague about their current status, so the veterans asked for clarification. A letter in December 1888 confirmed their worst fears, as the monuments had already been moved without the approval of the units. The GBMA had not exactly lied, but neither had they been entirely truthful about the process to the Veterans. The 15th Massachusetts monument now resided on the front line of Harrow’s Brigade, 235 yards south of the copse. The 20th Massachusetts monument was now in Hall’s Brigade’s front line, 125 yards south, while the monument to the 19th Massachusetts rested in the rear line of Hall’s Brigade, 119 yards away and on the far side of Hancock Avenue.

Veterans of the 15th spread the news to the other regiments and reported that many of their comrades were “thunderstruck” by the news as “they supposed as we did, that they would be notified before a change of location was made.” In 1891, following a court battle, the 72nd Pennsylvania came to Gettysburg to dedicate their monument, located at the advanced position while the Massachusetts monuments had been relegated to line of battle positions elsewhere. Arthur Devereux, who commanded the 19th Massachusetts at Gettysburg, called the situation “a travesty of truth.”

To mollify the Massachusetts veterans, Bachelder and the GBMA installed new bronze markers on October 15, 1891. These described the advance movements of each regiments, and most veterans accepted this as the best compromise they could get. Devereux wrote that the placement “is most satisfactory to myself and has settled any discontent among my men some of whom failed to be convinced of the reason for carrying back the monument.” However, due to the installation of the High Water Mark of the Rebellion memorial, the markers are not in the places the veterans chose for the monuments. The 15th’s plaque is in the position of the original 19th Massachusetts memorial. Only the 20th Massachusetts is in the location selected by the veterans.

Not all the veterans were satisfied, and as late as 1900, a senator supporting the Massachusetts soldiers sarcastically quoted the words of the GBMA at the first dedications, citing the promise to “watch and guard” the monument of the 15th Massachusetts. He caustically stated, “Now the way in which that memorial was watched and guarded was to remove it, without notice to the Regiment that had erected it.” Unfortunately, the markers were not always there to tell the story of the Bay Staters.

At some point in the 1950s, the markers were taken down, possibly because they fell into disrepair. The compromise that served as physical evidence of their actions in containing Pickett’s Charge were placed into storage. In 1993, the Civil War Roundtable of Eastern Pennsylvania from the Lehigh Valley searched for a preservation project to fund. The NPS had approved putting the plaques back up but lacked the funds to replace the now missing iron supports. They raised a total of $1,200, and the markers were finally replaced that Fall. They even hit an original monument foundation while installing a post!

Monuments are a reminder in stone and metal of how veterans wanted their service to be remembered. Removed from the immediate context of the copse of trees, the stories and sacrifices of the men from Massachusetts were often hidden behind the dramatic imagery of the 72nd Pennsylvania’s monument. The Pennsylvanian’s monument is iconic, so memorable as to be one of the most photographed locations as well as to be the design for the Gettysburg National Military Park commemorative quarter. Relegated to the original line of battle, or even the far side of Hancock Avenue in the way the Pennsylvanians took legal action to avoid, the Massachusetts monuments get much less attention. At least now, the posts and markers have been returned to the landscape, better illustrating the movements the regiments made while thwarting Pickett’s Charge.

Further Reading:

Fennell, Charles C. “A Battle From The Start: The Creation of the Memorial Landscape at the Bloody Angle in Gettysburg National Military Park” in Gettysburg 1895-1995:

The Shaping of an American Shrine. Gettysburg Seminar Papers 1995. http://npshistory.com/series/symposia/gettysburg_seminars/4/essay2.htm

Hartwig, D. Scott. “High Water Mark Heroes, Myth, and Memory” in The Third Day: The Fate of a Nation. Gettysburg Seminar Papers 2008.

http://npshistory.com/series/symposia/gettysburg_seminars/12/essay2.pdf

Hartwig, D. Scott. “Monuments, Memory, and Reconstruction at the High Water Mark.” (Lecture) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-U6om8T50Ms

Neu, Jonathan. “The 72nd Pennsylvania Monument Controversy,” in Gettysburg Magazine, Issue Number 40, January 2009.

Root, Edwin and Jeffrey Stocker. “Isn’t This Glorious”: The 15th, 19th, and 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiments at Gettysburg’s Copse of Trees. Bethlehem, PA: Moon Trail Books, 2006.

Trial of the Survivors of the 72nd Pennsylvania Versus the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association. Gettysburg National Military Park Library: Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

A longer series of skirmishes and battles than the Battle itself. Interesting article on the tribalism inherent in all proud regiments.

Thanks John. It really was quite complicated – the legal case for the 72nd monument had some VERY firey testimony on either side of the argument. A lot of pride here – and a lot of butting heads between veterans and the GBMA. You can understand the argument today, though. Everyone knows the 72nd PA. It’s a super iconic image, it was on the commemorative quarter to boot. But the Massachusetts regiments, due to removal away from the copse (and maybe the less dramatic designs) don’t get nearly as much attention from the average visitor.

Interesting read. I’ve always wondered about “the politicking” that might have transpired when it came to the markers and monuments at Gettysburg (and other battlefields). I was just there at the Gettysburg Battlefield the day before yesterday (Sunday Dec. 5) and spent quite a bit of time at “The High Mark” and that area, until the encroaching darkness chased us out. It’s good timing to read an article with this subject matter right now.

There sure was a great deal of politicking around monuments at Gettysburg – especially at the “High Water Mark” as you mentioned. Whether US or Confederate, there was often someone contesting the chosen location, inscribed language, or dedication speech.

thanks Jon … what a neat little story we would not have known about had you not dug it up … good for you … i will have check this out the next time i am in Gettysburg.

Thanks Mark! Knowing the layers on the landscape makes it a much more interesting place.

“Arthur Devereux called the situation ‘a travesty of truth.'” This is the same gallant officer who was the business partner of future Colonel Elmer Ellsworth in Chicago, where they maintained a patent office together. Small world.

Small world indeed. Devereux and the 19th Mass had some VERY strong opinions on the matter.

Dev was a war Democrat, if I remember, but fast friends they were indeed. They met up when he brought his US Zouaves to Boston.

This piece provides a helpful reminder of the role of the Massachusetts ‘ units on July 3. And if my memory serves, one or more of these regiments helped to turn back Wright’s Brigade in the early evening of July 2.

Indeed! There’s a monument to Colonel George Ward of the 15th Mass near Codori, marking his mortal wounding on the 2nd.

Great piece!

Thanks Kris!