Boomerang Bragg

This is the time of year when we see college and NFL coaches get the ax, and lots of other administrative changes in our favorite teams. Which leads me to this comparison, please bear with me.

The Confederate Army of Tennessee is well known for its internal issues, mostly centered around General Braxton Bragg. Nearly anytime you read about this army, the dissent is looming in the background, and ultimately Bragg was replaced. When did this start? One hundred and sixty years ago, right now.

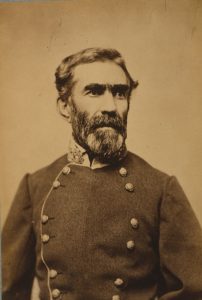

Braxton Bragg, LOC

For the better part of three days from December 31, 1862 to January 2 1863, the two primary western armies of the Union and Confederacy struggled in the fields and woods west of Murfreesboro. Neither force could drive the other off, as was typical of Civil War battles. The cost was 13,249 Union and 10,266 Confederates, for a grand total of 23,515 killed, wounded, missing, and captured, eleven times the population of Murfreesboro. The Federals also lost 28 guns.

At about noon on the 3rd Bragg met with his key commanders: Generals Leonidas Polk, William Hardee, and Patrick Cleburne. At his headquarters near the battlefield along the Nashville Pike, all agreed a retreat was necessary. The army was not strong enough to drive the Federal troops off, and it was not strong enough to stay where it was. The rest of the afternoon baggage and ordinance wagons began moving south along the roads to Shelbyville and Manchester. General John C. Breckinridge’s division covered the rear, and was the last Confederate force to pull out that evening.

The Army of Tennessee retreated south with their cavalry covering the infantry. Hardee’s Corps moved south along the muddy road to Wartrace, while Polk’s men trudged toward Shelbyville. Bragg halted the army behind the Duck River and made his new headquarters in the public square in the center of Tullahoma.

Though the indecisive battle at Stones River was frustrating and the men were exhausted, Bragg put a positive spin on it in his speech to the troops on the 8th:

“Soldiers of the Army of Tennessee! Your gallant deeds have won the admiration of your general, your Government, and your country. For myself, I thank you and am proud of you; for them, I tender you the gratitude and praise you have so nobly won . . . In retreating to a stronger position, without molestation from a superior force, you have left him a barren field . . .”

Few men in the ranks shared the general’s assessment. The inconclusive battle at Perryville in October, withdrawal from Kentucky, and now supreme effort at Murfreesboro that had come up short had combined to sap the morale of the troops. Newspapers, both local and as far away as Virginia, Georgia, and Alabama, were critical of Bragg’s retreat.

This was Bragg’s second major battle as army commander. He was already under scrutiny for the failed Kentucky Campaign; the Stones River Campaign ruined his reputation, setting the stage for future controversy and tension in the army’s high command. Retreat from Murfreesboro was not unreasonable given situation: his army had limited supplies and no reinforcements on the way, while the opposing force had both coming in steadily. Yet the withdrawal cast a negative light on the Bragg’s army.

In addition, there was great dissatisfaction and tension among the commanders of the army, and perhaps the most disastrous infighting to plague any Civil War army unfolded over the next few weeks. On January 10, Bragg held a staff meeting with Generals Patrick Cleburne, Leonidas Polk, William Hardee, Frank Cheatham, and John C. Breckinridge, asking if he held the confidence of the army, and stated if the answer was no, he would resign.

It was a two-part question: Bragg asked if the other officers agreed with the decision to retreat after the battle, and secondly, Bragg asked if they thought him fit to command. Can you imagine an NFL or College head coach doing this after a tough loss?

Bragg reminded the officers that many of them advised retreat, and concurred in the decision at the time, and asked them to state it publicly to quell the outcry in the newspapers. All of the officers agreed that withdraw from Murfreesboro was the right decision, but to his surprise, several commanders also said he should resign. Bragg was stunned and insulted by their comments and refused to step down, sparking a bout of infighting not seen anywhere else during the war.

Hardee noted that his subordinates agreed “that a change of command of this army is necessary.” Cleburne’s officers praised Bragg’s efforts but noted “that you do not possess the confidence of the army in other respects in that degree necessary to secure success.” Brigade commander Gen. William Preston wrote privately of “Boomerang Bragg,” and criticized him to many contacts, including some in Richmond.

Some big names and big egos were involved. It’s easy to understand why Bragg was offended: he had been an equal of Polk and Hardee: all were corps commanders just six months earlier at Shiloh. Leonidas Polk was the Episcopal Bishop of Louisiana. New Orleans was the largest city in the Confederacy and Polk’s prestige extended well beyond the pulpit and beyond the Crescent City. William Hardee was well respected for writing the US Army’s manual on infantry tactics before the war. Then there was John C. Breckinridge, a former Vice President and one-time Presidential candidate. His status would eventually elevate him to Confederate Secretary of War. Bragg was tangling with some well-connected and powerful men.

The result was a poisonous atmosphere among the army’s high command, and as time went on it became clear that the infighting and finger-pointing would undermine the army’s effectiveness. Bitterness developed between Bragg and three officers in particular: Frank Cheatham, Samuel McGowan, and Breckinridge.

Bragg wrote to President Jefferson Davis on January 17 that it was just a small number of officers who were dissatisfied and that many were new to the army and their opinions should not be counted. He also again justified the decision to retreat from Stones River. Davis sent General Joseph E. Johnston to investigate, and although he heard of the dissatisfaction firsthand, the troops seemed recovered from the setback of Stones River and he recommended not replacing Bragg. Writers have theorized that Johnston likely did not want to take command from a fellow officer….

Eventually Hardee, frustrated by the situation, got a transfer to another department. Polk and Cheatham continued to serve under Bragg, but grudgingly. The army would fight at Chickamauga and Chattanooga while enduring these internal divisions, until Bragg’s eventual resignation after Chattanooga. For two years, half the war, the army endured this infighting. We can trace the roots of the no-confidence in Bragg sentiment to the immediate aftermath of Stones River.

How much did Bragg’s medical problems contribute to his sensitivity and, perhaps, his mood swings?

I am not familiar with his health issues, please elaborate.

On pp 270-272 of Vol. II of “Braxton Bragg and Confederate Defeat,” Judith Lee Hallock wrote about Bragg’s many ailments such as “migraine headaches, dyspepsia, boils and rheumatism.” She also suggested that he was particularly susceptible to psychosomatic complaints during periods of great stress. He himself wrote about using Calomel, a mercury-based purgative that might have made his symptoms worse.

IIRC, he had contracted malaria in Florida during one of the Seminole Wars and he also had digestive issues. Moving into riskier territory, the Noe book on Perryville speculated on a psychiatric disorder (bi-polar?)

Johnston’s involvement is even more curious than described above – In March 1863, Davis issued and order (via Seddon, but from Davis) for Johnston to take direct command of the army and send Bragg to Richmond. This gives lie to the idea that Davis wouldn’t replace Bragg out of loyalty or friendship – the truth is, he DID replace Bragg in the Spring of 63. However, Johnston refused to obey the order, declining command, justifying his reason as the fact that Mrs. Bragg was too ill to move. Then, when she recovered, Johnston refused on grounds of his own poor health. Davis ultimately knuckled under, acquiescing to Johnston’s refusal, and Bragg remained in command.

I agree, it is really strange, especially given JEJ’s eagerness for an army command. I don’t understand his reasoning either in Jan ’63 or in the spring.

I remain amazed the Bragg name adorns one our largest military installations.

I know!

One of my ancestors, Thomas Jeffers of the Second SC Cavalry, mentioned General Bragg in a letter to his father describing the chaos of the Battles of Fort Fisher. Tom was not a fellow given to criticizing officers, so I thought it unusual that he wrote the following:

January 17, 1865

. . . On Sunday night the enemy having concentrated their forces assaulted and carried the Fort and immediately afterwards also attacked and captured Fort Buchanan. Some twenty-five hundred prisoners were captured. Gen Whiting who was sent down to take command of Fort Fisher and Col Lamb its former commander were both wounded and the supposition is that everything was in confusion and badly managed. . .

. . . Our troops still occupy the entrenchments in front of the Fort, but I have no doubt that we will be compelled to evacuate the City in a few days, as the enemy’s Gun Boats will command the River. I am afraid that the affair will prove quite a disaster to us . . . Gen Bragg commanded in person and you know he is always attended with bad luck.

that is a great turn of phrase about Bragg — ” … he is always attended with bad luck.”

Thanks for sharing, that is a great story! I recall the Wilmington newspaper, on learning that BB was assigned to its defense, saying something like, “Goodbye, Wilmington!”

Thank you, Bert. I think really gives some nice context & backstory to events of the fall of 63, Chickamauga and into Chattanooga. Much appreciated and certainly the other comments as well.

David Thank you. I was not aware of that information regarding Johnson

Samuel McGowan… or did you mean John McCown?