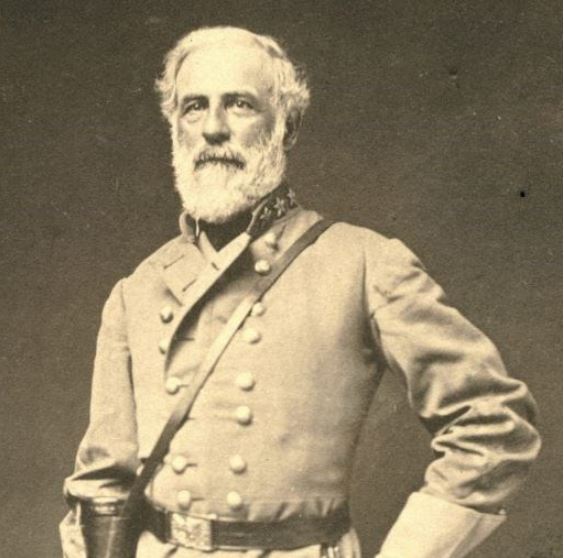

Robert E. Lee as a “Fallen Leader”?

I’m working on a volume for the Emerging Civil War 10th Anniversary Series on “Fallen Leaders.” As we did with last year’s symposium, the book considers leaders who not only fell, dead or wounded, on the battlefield but those who also “fell” from grace for one reason or another. With that informing my thoughts lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about Robert E. Lee.

Lee’s has taken some big hits in the past couple of years: the removal of his statue from Richmond, Virginia; the publication of Ty Seidule’s Robert E. Lee and Me and subsequent media attention it garnered; the release of the recent Lee biography by Allen Guelzo, whose book described Lee as “the Confederate general who betrayed his nation in order to defend his home state and uphold the slave system he claimed to uphold.”

“How do you write the biography of someone who commits treason?” Guelzo asked in his prologue.

Once upon a time, the audacity to ask such a question, fair as it might be, would have earned you the fiery, undying antipathy of Jubal Early. Just asked James Longstreet, who dared question Lee’s infallibility after the war and then made the mistake of getting down in the mud to wrestle with the pigs when they took him to task for expressing his opinion in the first place.

Lee’s modern partisans have taken great exception to recent discussions of whether Lee was a traitor or not, trying to dismiss the label as “presentism” (And presentism, is, indeed, an unhelpful lens for looking at history because it’s judgmental.) But describing Lee as a traitor is not a judgement, really, because the definition of treason is pretty straightforward, making the label factual, not judgmental. Nor is such an assessment “presentism.” As Frederick Douglass pointed out on Lee’s birthday in 1871, “He was a traitor and can be made nothing else.”

Nonetheless, Lee’s defenders were quick to make him into something else, and as the example of Jubal Early demonstrates, they have always been quick to rise up and shout-down the criticism.

A friend of mine told me the other day that, despite what I “hear in the news,” Lee is “as popular as he ever was.” I think that’s actually true among a certain segment of the population, particularly in the Civil War world. But I think there are other segments of the population where Lee never stood in particularly high standing. For some of those people, to speak up against Lee would have gotten them strung up from a tree; their silence at the time, though, should not be construed as agreement with so-called “general opinion.”

One person who did have the power to give voice to those undercurrents of discontent was W.E.B. DuBois. In the March 1928 issue of The Crisis—the quarterly publication of the NAACP, founded in 1910—DuBois offered a sharp but thought-provoking rebuke of Lee, written in the wake of Lee’s birthday that year.

Each year on the 19th of January there is renewed effort to canonize Robert E. Lee, the greatest confederate general. His personal comeliness, his aristocratic birth and his military prowess all call for the verdict of greatness and genius. But one thing—one terrible fact—militates against this and that is the inescapable truth that Robert E. Lee led a bloody war to perpetuate slavery. Copperheads like the New York Times may magisterially declare: “of course, he never fought for slavery”. Well, for what did he fight? State rights? Nonsense. The South cared only for State Rights as a weapon to defend slavery. If nationalism had been a stronger defense of the slave system than particularism, the South would have been as nationalistic in 1861 as it had been in 1812.

No. People do not go to war for abstract theories of government. They fight for property and privilege and that was what Virginia fought for in the Civil War. And Lee followed Virginia. He followed Virginia not because he particularly loved slavery (although he certainly did not hate it), but because he did not have the moral courage to stand against his family and his clan. Lee hesitated and hung his head in shame because he was asked to lead armies against human progress and Christian decency and did not dare refuse. He surrendered not to Grant, but to Negro Emancipation.

Today we can best perpetuate his memory and his nobler traits, not by falsifying his moral débacle, but by explaining it to the young white south. What Lee did in 1861, other Lees are doing in 1928. They lack the moral courage to stand up for justice to the Negro because of the overwhelming public opinion of their social environment. Their fathers in the past have condoned lynching and mob violence, just as today they acquiesce in the disfranchisement of educated and worthy black citizens, provide wretchedly inadequate public schools for Negro children and endorse a public treatment of sickness, poverty and crime which disgraces civilization.

It is the punishment of the South that its Robert Lees and Jefferson Davises will always be tall, handsome and well-born. That their courage will be physical and not moral. That their leadership will be weak compliance with public opinion and never costly and unswerving revolt for justice and right. It is ridiculous to seek to excuse Robert Lee as the most formidable agency this nation ever raised to make 4 million human beings goods instead of men. Either he knew what slavery meant when he helped maim and murder thousands in its defense, or he did not. If he did not he was a fool. If he did, Robert Lee was a traitor and a rebel—not indeed to his country, but to humanity and humanity’s God.

DuBois draws a parallel between events from 1861 to his own day in 1928, and we might find parallels to draw in our own (after all, aren’t people always looking for a “usable history”?). I am reminded of Mark Twain’s admonition that history doesn’t necessarily repeat itself, but it does rhyme.

Importantly, DuBois took harsh aim not only at Lee but at how Lee’s memory had been used (or, as he deemed it, misused). “[W]e can best perpetuate his memory and his nobler traits, not by falsifying his moral débacle, but by explaining it to the young white south,” DuBois said.

Seidule, once a member of that “young white south,” grew up to realize he’d been sold a false bill of goods (see more in this April 2021 blog post). “Robert E. Lee committed treason,” he eventually concluded.

The question of whether Lee was a traitor or not is not a moot argument. Some prefer a view that instead casts him as a “Virginia gentleman,” for instance (as a Lee-themed Virginia state license plate declares). And it’s true, as Guelzo admits, “no one who met Robert Edward Lee—no matter what the circumstances of the meeting—ever seemed to fail to be impressed by the man.”

But to define Lee that way is to overlook the fact that he, in Seidule’s words, fought “to create a nation dedicated to exploit enslaved men, women, and children, forever.” To applaud Lee’s brilliant military exploits is to forget that he achieved that success by killing “more U.S. Army soldiers than any other enemy, ever.” These are not inconsequential things, as inconvenient as Lee’s partisans find them. For 160+ years, they have been the ones to frame the debate, though, by controlling how we remember him.

Like any historical figure, Lee has much to teach us, good and bad. To learn from him, we must look at him honestly and accurately and from multiple perspectives, and we must resist both deification and vilification. As Guelzo suggests, a more holistic view can help us better understand. “[C]asting Lee in contradiction—” he writes, “as either saint or sinner, as either simple or pathological—is, in the end, less profitable than seeing his anxieties as a counterpoint to his dignity, his impatience and his temper as the match to his composure.”

Lee, the traitor, was a Virginia gentleman, just as Lee, the Virginia gentleman, was also a traitor. We can learn something from both of them, just as we can from listening to long-repressed voices represented by Douglass and DuBois—voices that finally roared to bring Lee down decades after they had to remain silent when he went up in the first place.

If Lee has fallen from his pedestal, perhaps that lets us finally see him as more human.

If Robert E. Lee was a traitor, why wasn’t he tried as a traitor? Maybe because he wasn’t really considered a traitor.by even the Union who defeated him. Leave it to the Emerging Civil War to never miss an opportunity to attack Confederates.

I would also ask why so many Federal Properties are named after CONFEDERATE Generals long after the War?

White supremacy/Sourthern political power/pandering.

It is my understanding The President of the United States at the time (my understanding includes General Grant) thought doing so would help mend the divisive attitude between the South and the North. Called “Mending” the torn fabric of the Nation.

It is my belief that in an attempt to bring the North and the South together it was vital to honor the “hero’s” from both sides. Hence the statues and the editorials fixing in the skill of the battle rather than the reason for the fight. The South was and still is very prideful the anger ran and still runs deep. Facts are the South it’s leader’s and military were all traitors to the USA

“… why wasn’t he tried as a traitor?”

Because he, like every other Confederate, was granted amnesty and a pardon for the crime of treason by President Johnson.

“Now, therefore, be it known that I, Andrew Johnson President of the United States, by virtue of the power and authority in me vested by the Constitution and in the name of the sovereign people of the United States, do hereby proclaim and declare unconditionally and without reservation, to all and to every person who, directly or indirectly, participated in the late insurrection or rebellion ***a full pardon and amnesty for the offense of treason against the United States or of adhering to their enemies*** during the late civil war, with restoration of all rights, privileges, and immunities under the Constitution and the laws which have been made in pursuance thereof.”

–Andrew Johnson, Proclamation 179, December 25, 1868

If Lee hadn’t been a traitor, then there was no reason for him to receive a pardon.

It was thanks to General Grant and his powers of persuasion with President Johnson that Lee never faced a trial for treason. As Grant put it, “In my opinion the officers and men paroled at Appomattox Court-House, and since, upon the same terms given to Lee, cannot be tried for treason so long as they observe the terms of their parole.” Grant knew that continued ill will between North and South could be fatal for the country and that unification was imperative. (Maybe we should learn something from him.) And of course, Lee had to wait a little longer than others for his amnesty, which was not granted along with those for other Confederates. It took more than 100 years to achieve, his amnesty application having gone rather suspiciously missing thanks to William Seward.

It is complicated. That’s all I can say.

An interesting way to learn and better understand the man as a man and the discord with which he had to live during and after the Civil War. I would guess Lee, more than anyone, didn’t want statues or adulations to follow him into his later years. He was troubled by the thought he could be brought up on charges of treason and, to my understanding, probably carried that burden to the grave. As some say, “My Country, right or wrong!” the line at his time was more like “My State, right or wrong.” Does that mean Lee was “FOR” or “AGAINST” slavery as a man? Or does it possibly mean he took Virginia, right or wrong, as the more just cause for him? How about the hundreds of thousands of non-slave owners who willingly joined “The Cause” and died in the process? Are they seen as traitors as well? Does it count that the Nation forgave him his “sins?” President Ford signed a full pardon for General Lee on the front steps of the Custis Mansion.

1. Lee was a traitor because he participated in an insurrection against the Government of the United States of America.

2. Federal properties were mistakenly named after Confederate traitors , in the mis-guided spirit of reconciliation. Fortunately, that mistake is being corrected.

I think we only have this traitor debate about Lee because Lee is seen as a “good/great” general. For example, has anyone heard a debate about if Joe Johnston, Braxton Bragg, A.P Hill, Jubal Early, John C. Pemberton, or Simon Buckner was a traitor?

I hope at some time we can talk about Lee’s failure as a General, He never learned from his failures. He was rarely, if ever, able to get his Generals to coordinate their attacks. However, his plans kept calling for them to do so.

Look at the case of Stonewall Jackson. When he is working directly and continually with Lee, we have the Jackson of the Seven Days, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. When he is operating “independently” of Lee, we have the the Stonewall of the Valley Campaign and Jackson’s attack at Chancellorsville.

This subject is complicated and difficult to consider without the “presentism” and judgments of today.

War causes us to make difficult choices. Lee could not betray his family-relatives (most of us cannot relate to this, myself included.) He was compelled to physically defend his family-relatives and to physically defend Virginia. He too yearned to bring peace to the two sides. Yes, he was caught in a paradox. I don’t think Lee ever fell from grace. His best moments came after the war when he sought to heal the nations. That said, society should objectively and respectfully examine his strategy and strategic leadership. His failures can teach us a lot. It is definitely a complex subject.

George Thomas betrayed his family and they disowned him.

I admire the fact that you don’t shy away from the difficult and controversial aspects the Civil War presents for us, Chris. Nor do others at ECW. Sticky wickets and cans of worms seem almost a specialty at ECW. That’s not a bad thing. It’s good to have a forum on the web where subjects like this one can be aired and where they generate more light than heat. The WEB DuBois quote is an interesting one and one I’ve never seen before. I truly wish the issues he raised that lingered sixty years after the war had dissipated now that we’re 160 years out. But then moral courage has always been in short supply, and if anything there is less around today than ever.

Thanks, Jim. I don’t have all the answers, for sure, but my belief is that ECW, as a community of writers and readers, can come to greater collective wisdom by discussing and debating.

Chris-thank you for this thoughtful post. DuBois is correct that people do not fight for abstract theories of government. However, I believe that he is wrong in assuming that many people in the South fought for privilege and property. It is true on a macro level that the South fought the Civil War for the preservation of slavery. People, however, live on a micro level and many people in the South, like people everywhere through time, believed that they were fighting for their homes, families, and communities. That is a very, very powerful human emotion that has been lost in the shuffle in the discussion of Lee.

From our point of view, Lee was a traitor, but the decision that he faced in 1861 was a decision that I certainly would not want to face. Today, we can scoff at his decision to side with his state, but there was a reason why the United States was referred to in the plural rather than in the singular before the Civil War.

As you point out, Lee was a “Virginia gentleman”, a concept that served our country well at the end of the war. We are beyond fortunate that the Civil War did not devolve into decades of guerrilla warfare and sectional strife. Lee deserves some credit for that, a point that was not lost on Dwight Eisenhower, who had a portrait of Lee in the Oval Office.

As you also point out, Lee has “fallen from his pedestal”, but what replaces it? The meanness of our current national discourse? It is not that difficult to tear down a statue, but it is difficult to cultivate virtues such as duty, courage, and honor. Lee and many others in our rich history exemplified those virtues and when we tear them down, either literally or figuratively, we also tear down an opportunity to learn those virtues.

“The meanness of our current national discourse?”

You know what was meaner? Slavery, lynching, black codes, peonage, Jim Crow, Redlining, and White Supremacy. I’ll take the current “meanness” over historical “pleasantries”.

That is one way to look at our history. I prefer to look at our history with gratitude for the people who made shattering sacrifices to advance the idea that each individual has inherent dignity as a child of God. I think of Washington’s army, the men who struggled in the Civil War, and the Freedom Riders who fought against raw racism during a period when I was one or two years old. How often do Americans express gratitude today for those who came before us? There is a meanness in today’s national discourse and it comes from an attitude of complaint rather than gratitude.

As for Lee, yes he was on the wrong side, but we get born into our circumstances. He acted with honor and do not underestimate the importance of that example. For the defeated, impoverished white Southerners, he offered a code of conduct that rose above hatred and self -destructive behaviors. His legacy is not tidy, but human beings are not tidy by nature.

“For the defeated, impoverished white Southerners, he offered a code of conduct that rose above hatred and self -destructive behaviors.”

Wow, was that code ever ignored! They failed to rise above their hatred until the US Government was once again forced to step in and end their codified hate.

TK is absolutely correct.

I recall how US Marshalls escorted Afro Americans to schools after Brown v Board of Education.

And I recall when John Kennedy sent National Guardsmen to allow James Meredith register at ole Miss.

That’s a great response, Bill. Thanks.

It is, indeed, harder to tear down than build up, and I have been especially disillusioned by the meanness of our current national discourse. In that area, Lee could serve as a good example: he was guided by decorum and respect even during difficult conversations.

The Civil War did devolve into decades of guerilla warfare and sectional strife. Over the very issue on which Lee very publicly refused to concede, even after the war. His devotion to white supremacy.

Lee also spent significant portions of the war drawing his sword against his fellow Virginians, including those wishing to become West Virginia.

He should have been tried and hanged.

General George Thomas was a Virginian, he owned slaves, he took the same oath as Lee when he became an officer. After Sumter he wrote to his wife that his oath was his honor. He fought well for the Union.

When Lee surrendered to Grant, Grant asked Lee to help him with the surrender of other Confederate forces, Lee declined assistance.

Like you, I’m a George Thomas fan, but most people in the South went the other way. Lee believed that he did not have the authority as the general of a single field army to make decisions best left to the civilian authorities. He did, however, encourage his fellow former Confederates to be good citizens after the war and he advised against guerrilla warfare.

Lee as general in chief of Confederate forces as of February 1865, so he could have interpreted his position as having the authority. He made a reasonable decision not to, but an argument could have been made the other way, too.

Guelzo and ECW are operating on the premise that secession was illegal. Save us all a lot of trouble and read “Secession on Trial”, Nicoletti. It will deliver you to the position taken by the country, after some time to think about it; that the whole things was a mistake, or a lot of mistakes, both sides had their points, there was plenty of blame to go around, and the best thing to do was to move forward while learning from it. Secession, as it turns out, was not illegal. It’s become popular to use Lee as a focal point for the Union’s need to make a punching bag out of the South, covering for the many missteps that led to the Union’s reiteration in the US of the European practice of “might makes right”, all the while pretending to be adhering to a Constitution designed specifically to avoid that – a “nation of laws”. You really do need to consider carefully continued use of this epithet, and also of the continued accusation that the South, even in a macro sense (billhenck above), fought to preserve slavery. Making that accusation reveals lack of any in-depth knowledge of that history, both long term and the immediate term. I’m not giving history lessons in a blog comment section, but it’s an easy path to a soundbite on that one; reading available documentation on the subject is harder and takes longer. Those soundbites will be lost in the process and you will be faced with confronting some hard truths.

The Founding Fathers never intended the United States to dissolve. We know that from the Articles of Confederation. Though not the law of the land, the Articles are still a document of this Nation’s founding.

The fact that the first 7 states to leave the Union did so after the election of the Republican candidate who ran under the platform of not extending slavery to the territories, is reason enough to know that the South left because of the issue of slavery.

And the Cornerstone speech solidified that poi=sition.

The late Michael Phipps, former military man and Gettysburg guide, thought that Guelzo was a clown as an historian. He thought his book on Gettysburg was irredeemably flawed. I doubt his book on Lee, or Seidules’ Augustinian Mea Culpa would provoke different comments. To claim that Lee fought for slavery, (which he could have fought for by staying in the Union) or could be a “traitor” is victor’s logic, and selective historical cherry picking at its best. How can you be a “traitor” to a country you deny has constitutional authority over you? The Supreme Court was not even called to directly address the constitutional issue until it became a tame partisan one, with predictable results, as was Dred Scott from an earlier court. The rightness or wrongness of the reasons behind Southern Secession don’t affect the fundamental confusion on the basic right to succeed. Even abolitionists encouraged their states to consider it in the 1850s.

1..It’s a bit presumptuous, and a straw man argument, to infer what someone would say about a book he has never read.

2. Since the South was built on slavery,( the Cornerstone Speech), Lee did fight to preserve that institution, so yes…he fought to preserve slavery.

3. Last I checked, Lee was an officer in the US Army, and took up arms against that country….The United States of America. Let’s not try and change the definition of traitor…ok?

4. To bring up the SC is another straw man argument.

5. There was nothing predictable about Dred Scott. No where in the US Constitution does it say that Blacks were to be denied citizenship.

6.Tell me…what States where abolitionists were the dominant populace, left the Union?

You are VERY right about point 2. Indeed the Confederate Courts in Virginia had to force Robert E. Lee to free some of his wife’s slaves–as he was supposed to have done several years before as per his father-in-law’s will.

Sorry, but comments made by Phipps over the years in his CW blogging make my use of him very reasonable.

You really are trying to define Lee’s reasons for fighting for the Confederacy in terms of why the Confederacy was founded? Stephens was a Georgian the deep South clearly went out over slavery. If slavery was the be all and end all issue for Virginia, why didn’t it go out in December, January or February? Why did it initially vote against secession? Initially, like every other remaining state in the Union it knew that Lincoln had pledged not to touch it where it existed. If Lee as an individual wanted to fight for a slave Republic, he could have stayed in the Union.

DuBois also asserts that the Virginians were fighting for property and prestige. They already had that in the Union, and we’re quickly diversifying their economy. As far as Lee, how would “treason” benefit him? His only property of note, the Custis mansion, was right in the bull’s eye of any National offensive.

I’m sorry you missed the point about a stacked deck in the Taney Court. I thought the resulting horribly flawed judicial jurisprudence perfectly echoed that court’s divisions.

And thank you for noticing the obvious- there weren’t enough abolitionists to achieve what they believed the states had a constitutional right to do.

Frankly, I agree with Texas v. White, and agree that the Amendment Process was the proper and only grounds of appeal to permit secession.

Sorry, but no reputable historian would make a comment about a book they have not read. Personal animus has no standing. And in fact, knowing someone has a personal animus, makes their opinion irrelevant.

If you have read the 4 volumes of The Proceedings of the Virginia State Convention of 1861 as I have, you would read that those in favor of immediate secession did all they could to maneuver to keep the convention in session, waiting for an event to tip votes there way. Not one delegate ever criticized slavery. Slavery and its protection were at the forefront or their motivations. Recall that before slaves were property, and that Virginia had more in common with the Lower South than it did with the North. I am sorry you missed those points.

If Lee wanted to fight against slavery, he could have stayed in the US Army. He didn’t. He fought to preserve slavery.

There were enough States to make a Constitutional right.

I’m sorry you missed the point that the vote in the Dred Scott decision was along sectional lines.

You all use the term traitor and treason very casually. You assume the term applies to Lee, and presumably to the other 800,000 or so Confederate soldiers. In a casual sense or street sense, Lee might be accused of treason. But, the law requires something more specific. The legal definition of “treason” requires an overt act which manifests a desire to betray one;s country. Cramer v. U.S., 325 U.S. 1 (1945).

But, Lee’s action and that of the other 800,000 members of the CSA military manifested more renouncing loyalty to one country and adhering to a new country. I served in the US Army, Reserves, National Guiard for 20 plus years. If I had resigned my commission to join the Mexican Army just prior to a fire fight on the border, I might be accused of treason by some. But, to others, I would be a patriot – depending on *why* I made that change.

But, the biggest hurdle for the treason charge is that while abandoning the US, Lee manifested an extraordinary loyalty to his home state. What sort of treason is it if a person in so doing actually demonstrates extreme loyalty?

Tom

Robert E. Lee had a beautiful mind. His dedication to duty, as he saw it, should be studied and understood. Having concluded that it was his duty to follow Virginia, Lee desperately hoped Virginia would not secede. Offers of high positions in Northern and Southern armies did not tempt him. He was persuaded to resign before Virginia seceded because he knew that he could be ordered to take command of some or all of President Lincoln’s 75,000 volunteers. Resigning under orders would have been a disgrace. His commanding officer, General Winfield Scott, considered Lee’s decision to resign a “mistake,” not treason. Neither can I regard his decision as treasonable, and I don’t really understand the relevance of the discussion. Wasn’t his decision similar to that of his mentor George Washington?

The defense of slavery persuaded Lee to resign.

President Andrew Johnson thought he was a traitor….hence his pardon.

There is no evidence for your first claim. As to the second, Lee never received an individual pardon from Johnson. Johnson issued a General Amnesty in 1868. Lee’s citizenship was restored by President Gerald Ford in 1975.

Lee had slaves, and the South left the Union for fear that legislation would end their peculiar institution. And because slaves were property, Virginia had more in common with the Lower South that left the Union than it did with the rest of the United States.

Johnson thought the Southerners were traitors…hence the pardon.

Lee must have owned slaves, because there is a record that he inherited slave(s) when very young. But, he apparently divested himself of them quickly, because no record, such as census records, notes Lee owning any slaves. Later in life, he managed slaves which were owned by the Estate of George Washington Park Custis. But, no, legally, he did not “own” the Custis slaves. They were owned by the estate.

Tom

Myth: “Robert E. Lee didn’t own slaves.”

The claim that Robert E. Lee did not own slaves is often paired with the claim that Ulysses S. Grant did own slaves during the Civil War. Both claims serve to distance the Confederacy from its core justification and suggest United States hypocrisy on the matter of race. Both claims are false.

Robert E. Lee personally owned slaves that he inherited upon the death of his mother, Ann Lee, in 1829. (His son, Robert E. Lee Jr., gave the number as three or four families.) Following the death of his father-in-law, George Washington Parke Custis, in 1857, Lee assumed command of 189 enslaved people, working the estates of Arlington, White House, and Romancoke. Custis’ will stipulated that the enslaved people that the Lee family inherited be freed within five years.

Lee, as executor of Custis’ will and supervisor of Custis’ estates, drove his new-found labor force hard to lift those estates from debt. Concerned that the endeavor might take longer than the five years stipulated, Lee petitioned state courts to extend his control of enslaved people.

The Custis bondspeople, aware of their former owner’s intent, resisted Lee’s efforts to enforce stricter work discipline. Resentment resulted in escape attempts. In 1859 Wesley Norris, his sister Mary, and their cousin, George Parks, escaped to Maryland where they were captured and returned to Arlington.

In an 1866 account, Norris recalled,

[W]e were immediately taken before Gen. Lee, who demanded the reason why we ran away; we frankly told him that we considered ourselves free; he then told us he would teach us a lesson we never would forget; he then ordered us to the barn, where, in his presence, we were tied firmly to posts by a Mr. Gwin, our overseer, who was ordered by Gen. Lee to strip us to the waist and give us fifty lashes each, excepting my sister, who received but twenty; we were accordingly stripped to the skin by the overseer, who, however, had sufficient humanity to decline whipping us; accordingly Dick Williams, a county constable, was called in, who gave us the number of lashes ordered; Gen. Lee, in the meantime, stood by, and frequently enjoined Williams to lay it on well, an injunction which he did not fail to heed; not satisfied with simply lacerating our naked flesh, Gen. Lee then ordered the overseer to thoroughly wash our backs with brine, which was done.

State courts in both 1858 and 1862 denied Lee’s petition to indefinitely postpone the emancipation of his wife’s enslaved people and forced him to comply with the conditions of the will. Finally, on December 29, 1862, Lee officially freed the enslaved workers and their families on the estate, coincidentally three days before the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect.

Robert E. Lee owned slaves. He managed even more. When defied, he did not hesitate to use violence typical of the institution of slavery, the cornerstone of the cause for which he chose to fight.

For further reading:

Adam Serwer, “The Myth of the Kindly General Lee,” The Atlantic (June 4, 2017)

Diane Cole, “The Private Thoughts of Robert E. Lee,” U.S. News and World Report (June 24, 2007)

Elizabeth Brown Pryor, Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters (New York: Penguin Books, 2007)

===========================================================================

One also must look at what W.E.B DuBois said about Joseph Stalin. In 1953 he wrote “Joseph Stalin was a great man…” I think I’ll take Eisenhower’s character judgment of Lee over DuBois. Anyone that likes and thinks Stalin is a great man should be called into question on their judgment. DuBois history of Lee is flawed too (for example, Lee was no aristocrat), but let’s not let that get in the way of using his interpretation of Lee to promote a biased viewpoint.

Eisenhower also was close friends with Douglas S. Freeman and heavily influenced by Freeman’s views of Lee and the Lost Cause. Sure, Lee was a brave and competent commander but he violated his Oath to the United States and was responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of US troops. I prefer to honor Southerners who remained loyal to the USA.

Booker T. Washington said: There were two men in the South who first showed interest in the Negro and saving his soul: Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.

Tom

Did they ever say anything about giving African Americans their freedom? Giving them a wage? How about building schools? educating them? How about making them citizens and giving them the vote?

Just curious.

Yes, basically,. That is what Washington was saying. To educate hem in the Christian faith and the Bible, they had to learn to read – at a time when educating slaves was illegal.

But, if you are asking Lee and Jackson to satisfy some definition of 2000’s era liberal democratic views, you will be disappointed.

Tom

You forgot to add to the quote by Washington…”through the medium of the Sunday school.”

Actually there was no mention of giving Afro Americans their freedom, the right to be a citizen, the right to vote and heaven forbid, a living wage, let alone any wage.

I’d have liked to have Lee and Jackson satisfy a definition of of all men being created equal. That too was a liberal democratic view.

I am curious about the claim that the Confederate Courts had to force Lee to manumit the Custis slaves. I know he made a point to do so after the Battle of Fredericksburg when he was otherwise heavily occupied! Knowing Lee, I can’t imagine that he decided to do so at that time for any other reason than he thought it the right thing to do.

He did after all go the trouble of issueing freedom certificates even to the slaves who were safely within Northern lines and, therefore, already free.

Tom

Not during the Gettysburg Campaign. Rebels. kidnapped free Blacks and sent them South into bondage.

I am no expert on the subject, but if my memory serves from sources I have read over time, Lee freed the LAST of the slaves he inherited a couple of months AFTER the 5 year stipulation in his father-in-law’s will ended. His FIL died in October of 1857. Because of the disarray and enormous, long-standing and long-term debt his FIL’s estate was in, Lee did petition the court’s to extend the deadline in hopes he could retire the debt. Whether any of the courts ruled on his petition or that of any of the slaves themselves, I do not know, well, I can’t remember. He freed the last of his slaves just a few days before the Emancipation Proclamation officially went into effect.

LEE accidentally brought 200 black men women and children from the Gettysburg Campaign with him on his retreat to Richmond. They were just as surprised as he was….I believe this was about the time they had a pie eating contest in the A of NV to raise money to send them back with apologies. My GG Grandfather mentions this in his journal. We kept the pie pan in the family as proof in case the internet was invented.