The Romney Expedition: Confederate Tales of Snow and Ice

Part 1 of a series

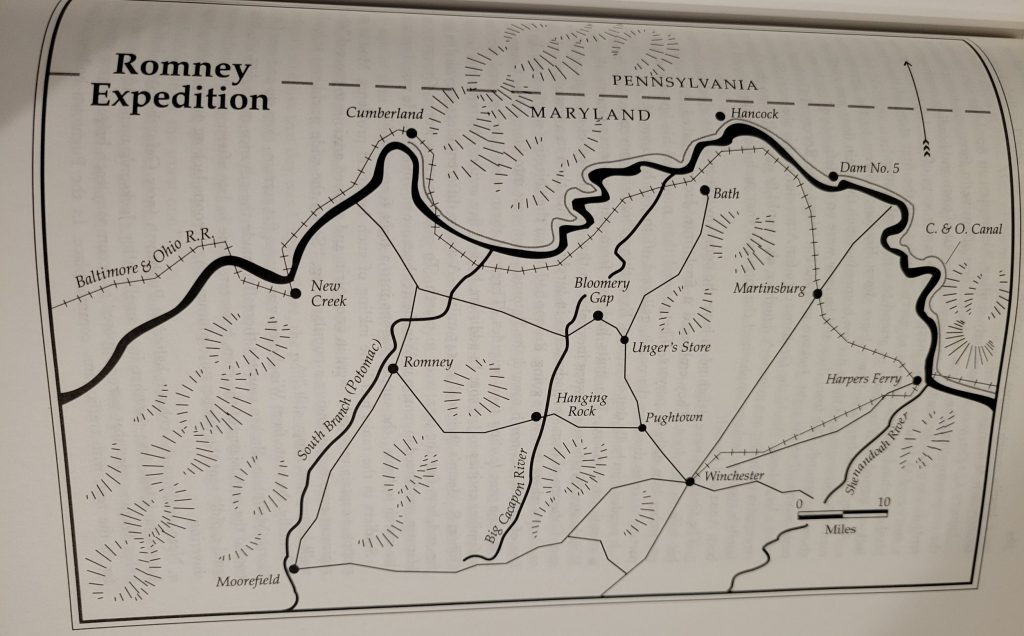

In January 1862, Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson set off from Winchester Virginia and headed west into the mountains of western Virginia, intending to capture the town of Romney, remove Union troops from the lower (northern) part of the Shenandoah Valley, and threaten the railroad line and canal system. Jackson had hatched the plan in November 1861, shortly after taking command of the Confederacy’s Valley District in the military’s Department of Northern Virginia. Removing all Federal troops from his district and successfully raiding the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal seemed like an ambitious start for Stonewall.

The campaign — typically called “The Romney Expedition” — started on January 1, 1862, as Jackson left Winchester with approximately 9,000 men, leaving 2,000 troops behind to guard his headquarters city. Jackson’s men had already attacked the C&O Canal in December, creating some destruction along the canal’s dams. That Dam Expedition (the soldier’s preferred the curse version of pronunciation/spelling) had been a chilly introduction to the rest of the winter’s operations.

By all appearances, the march toward Romney couldn’t have started at a better time. The departure day at Winchester featured warm, almost spring-like weather. However, the rest of the weather forecast was grim. A winter storm arrived that night, pelting the terrain, roads, and soldiers with snow, sleet, and ice. Jackson refused to turn back.

Over the next two weeks, Stonewall pushed his men up the mountainous roads, captured the town of Bath, forced Union General Frederick Lander to retreat, fought the Battle of Hancock (January 5-6), and then pulled back toward the town of Romney. Meanwhile, Union General Benjamin F. Kelley moved toward Winchester, skirmished at Hanging Rock Pass, captured two cannon…and then retreated — giving up a possible advantage to advance on Winchester. Jackson captured Romney on January 14 and settled to plan his next moves: an advance to Cumberland, Maryland. However, more winter storms and fierce wind chill caused his soldiers’ morale to plummet and Jackson gave up the idea of more offensive strikes that winter. To hold Romney, Jackson left General William Loring’s Division. Then, taking the Stonewall Brigade and Ashby’s Cavalry, Stonewall headed back to Winchester, leaving a trail of dissention in his wake.

To gain a better appreciation for the conditions of this campaign and what Jackson forced his troops to endure, here are some primary source complaints from the Confederate men in the ranks:

Alfred Mallory Edgar, a private in the 27th Virginia Infantry (Stonewall Brigade), later recalled:

This morning, the first day of January, 1862, we start on a march in the direction of Romney. The morning is bright and war, a very comfortable day, much like spring. We start off in good health and spirits, but towards evening there is a great change in the weather. The wind rises, and we notice that it is getting considerably colder…. We are apprehensive that we are starting on a winter campaign, and feel some regret at leaving our comfortable winter quarters, Camp Harmon. Next morning the weather has gotten several degrees colder, and we suffer a good deal. The snow and sleet are falling. The roads that were nice yesterday are getting to be almost impassible for our wagons because of the ice…. [The campaign continues and] often our wagons cannot keep up with us, and we have to bivouac with nothing but a blanket, and possibly an oilcloth, just what we can carry. So our suffering from this intense cold is very great. [Edgar repeatedly notes the declining health of his regiment] ….It is the 10th of January. The sickness among the men continues, and is, I am afraid, increasing.[i]

Despite the difficulties, Edgar believed the Stonewall Brigade would not lose confidence in General Jackson, creating a divide between other units that would play out in the aftermath of the campaign.

John O. Casler of the 33rd Virginia Infantry (Stonewall Brigade) added his own recollections of the Romney Expeditions to his memoirs:

We went on to the river, opposite Hancock, Md., and threw a few shells across We captured some government stores and remained there two days, the weather being very bad all the time — snowing, sleeting, raining and freeing. We would lie down at nights without tents, rolled up head and heels in our blankets, and in the morning would be covered with snow. Every few minutes some one of the party I was sleeping with would poke his head out from under the blankets and let in the snow around our necks, when he would get punched in the ribs until he would “haul in his horns.”

We then marched back towards Winchester and camped at Unger’s Store. The roads were one glare of ice, and it was very difficult for the wagons and artillery to get along. Four men were detailed to go with each wagon in order to keep it on the road on going around the hillside curves. I was on one details, and we would tie ropes to the top of the wagon-bed in the rear, and all swing to the upper side of the road. The horses were smooth shod, and in going up a little hill I have seen one horse in each team down nearly all the time. As soon as one would get up, another would be down, and sometimes all four at once. [Heading toward Romney] The third day we entered Romney, and found the enemy had evacuated the place on hearing of our approach. The weather was extremely rough. We were all covered over with sleet, and as it would freeze fast to us as it feel we presented rather an icy appearance.[ii]

Another account of the common soldiers’ miseries on this expedition appears in Henry K. Douglas’s volume. Although many of Douglas’s tales should be viewed with some skepticism for potentially stretching the truth, this one does have an air of authenticity and grim humor:

It was the most dismal and trying night of this terrible expedition. It had been and was still snowing lightly, and the small army was in uncomfortable bivouac. A squad of soldiers in the Stonewall Brigade had built a large fire and some of them were standing and some lying about it wrapped up in their thin and inadequate blankets. The sharp wind was blowing over the hills and through the trees with a mocking whistle, whirling the sparks and smoke in eyes and over prostrate bodies.

A doleful defender, who had been lying down by the fire, with one side to it just long enough to get warm and comfortable, while the other side got equally cold and uncomfortable, rose up and, having gathered his flapping blanketing around him as well as possible, stood nodding and staggering over the flames. When the sparks set his blanket on fire it exhausted his patience and in the extremity of his disgust he exclaimed, “I wish the Yankees were in Hell!”

As he yawned this with a sleep drawl, around the fire there went a drowsy growl of approbation. One individual, William Wintermeyer, however, lying behind a fallen tree, shivering with cold but determined not to get up, muttered, “I don’t. Old Jack would follow them there, with our brigade in front!”

There seemed to some force in the objection, but the gloomy individual continued, “Well, that’s so, Bill, — but I wish the Yankees were in Heaven. They’re too good for this earth!”

“I don’t!” again replied the soldier behind the log, “because Old Jack would follow them there, too, and as it’s our turn to go on picket, we wouldn’t enjoy ourselves a bit!” The discomfited soldier threw himself to the ground with a grunt, and all was quiet but the keen wind and crackling flames.[iii]

The weather and campaign’s hardships factored into the leadership dilemmas that Jackson faced during and after the Romney Expedition. However, some of his experiences of the campaign differed from his men and will be explored in Part 2.

————

Sources:

James I. Robertson, Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend, (New York, Macmillan, 1997).

Robert Lewis Dabney, Life and Campaigns of Lieutenant General Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson, Reprinted, (Harrisonburg, Sprinkle Publications, 1983).

[i] Alfred Mallory Edgar, My Reminiscens of the Civil War with the Stonewall Brigade and the Immortal 600, (Charleston: 35th Star Publishing, 2011), Pages 37-39.

[ii] John O. Casler, Four Years in the Stonewall Brigade, (1906), Pages 62-63.

[iii] Henry Kyd Douglas, I Rode With Stonewall, (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1968), Pages 20-21.

Thanks! This is often an over-looked part of the Campaign.

There is a great account of this campaign in Sam Watkins memoir “Company H.”

Yes, thanks for mentioning it. Watkins is quoted later in this series and there’s a link to another post that Chris Mackowski wrote about Co H in western Virginia.

Great blog! I forgot about this expedition. It’s amazing the physical stamina these soldiers had.

Indeed. I suppose I shouldn’t complain about the ice on the sidewalks?

William “One Wing” Loring… someone should have listened to what he was saying.

A great part one of this campaign, often overlooked…am very much intrigued by Jackson’s Romney expedition.