1862: Leaving Winchester

If Union entrepreneurs had been hawking tickets for best viewing places for the next battles to any enthusiastic picnickers who hadn’t learned their lesson at First Bull Run, the tickets would’ve gone cheaply for the seats in the Shenandoah Valley. Compared to General McClellan’s grand embarkation and maneuver to the Virginia Peninsula, General Nathaniel Banks’s campaign into the Valley looked a bit boring. Drive back the Confederates, secure the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and guard the “backdoor” to Washington City while McClellan and the Army of the Potomac seized Richmond, the Confederate capital.

Trying to turn back the knowledge of the outcomes of historic campaigns is challenging. Erase the details of the famed 1862 Shenandoah Valley Campaign and picture the moment when Federal troops advanced on Winchester and “Stonewall” Jackson gave up the town. Who could have imagined the Confederate withdrawal from Winchester is now seen as one of the starting moves of the famous (or infamous) campaign?

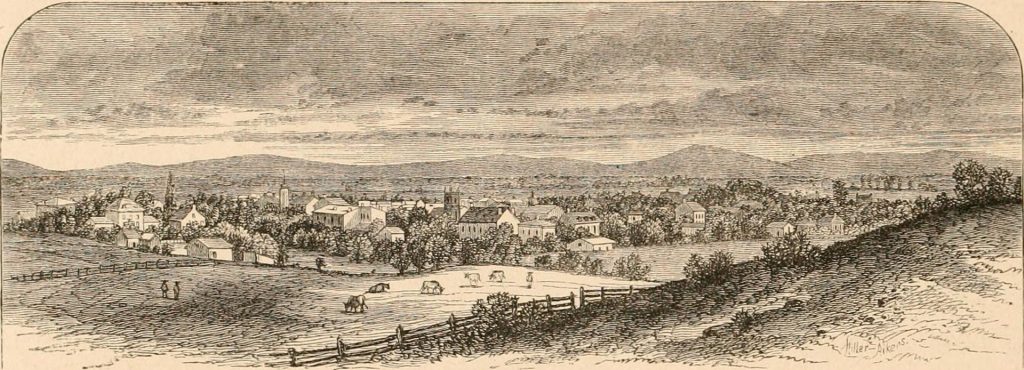

After-all, it started rather well for General Banks. Joined by General James Shield’s division from Martinsburg, Banks’s gathered force of nearly 40,000 Union soldiers began to advance south toward Winchester, the small city holding all the major crossroads of the lower Shenandoah Valley. (In the Shenandoah Valley, “lower” refers to the northern part of the region, closest to the Potomac River; the main rivers flow south to the north in the Valley, creating a unique description of directions.)

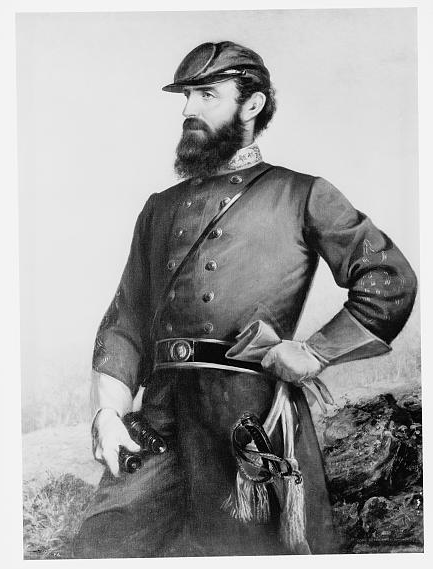

Confederate commander General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson watched the Union advance in annoyance. The Romney Campaign and his envisioned strategy of outposts across the western Virginia mountains was supposed to have prevented or slowed this rather quick Federal advance toward his headquarters at Winchester. A nettling reminder of the possible disloyalty within his own ranks and the easily swayed politicians who had tried to undermine him earlier in the year. He had got his way and a nearly independent command, but he had not got his network of outposts.

As early as March 7, 1862, Confederate cavalry pickets skirmished with Banks’s troops. Forced back, Colonel Turner Ashby’s cavalrymen could not hold a defensive line, and Jackson made preparations at Winchester. While infantrymen strengthened their limited fortifications, the general ordered his army’s wagons and extra supplies out of town. On March 8, Major John Harman, Jackson’s quartermaster, had wagons ready to roll south, but still thought “Jackson will certainly make a stand if he can do it without the risk being too great.”

Though outnumbered nearly six to one, “Stonewall” mentally prepared for battle at Winchester. However, under orders, the army had started to move south of the town. On March 11, Jackson called a council of war and laid out his plan: a surprise attack in the dark morning hours. General Richard Garnett, commander of the Stonewall Brigade, objected, pointing out that most of the regiments had followed the supply wagons, and the troops now slept, several miles from the town itself. The troops could not be recalled in time for a night attack.

Jackson protested, at first. His soldiers could certainly march in the darkness and organize for an attack! The other officers continued to reason that the situation was beyond repair and that it would be best to save the army, rather than risk a disorganized route. They could fight another day.

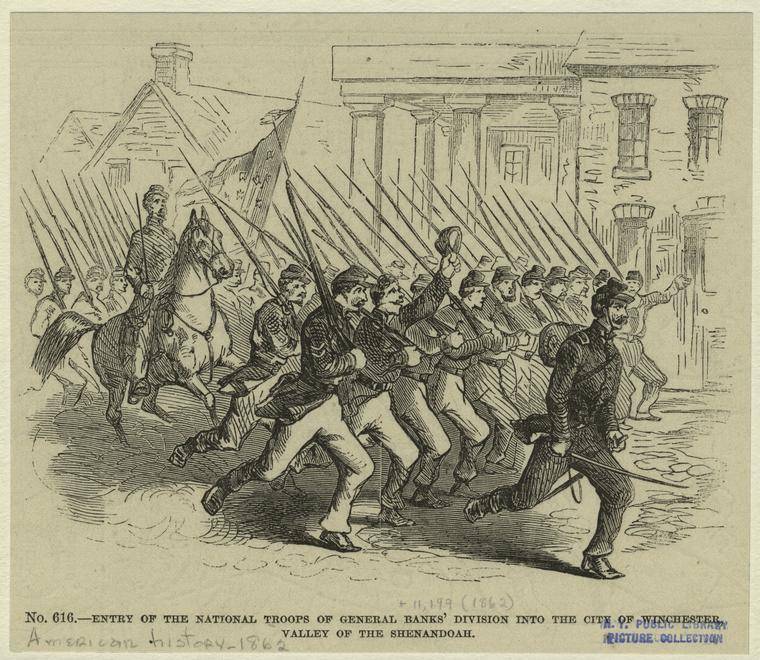

Finally, “Stonewall” acquiesced, perhaps feeling undermined again. The remaining Confederate guards in Winchester received orders to withdraw. The Valley Campaign looked successful for General Banks in the opening days, as the Confederates abandoned Winchester without a serious fight.

Dr. Hunter McGuire, a staff officer and the medical director for Jackson’s army, departed with Jackson. McGuire had grown up in Winchester and left behind his mother and sisters as the Confederate army retreated. The topography slopes gently upward on the roads leading south from Winchester, giving a vantage point of the civilian residences, and McGuire later recalled:

I rode with the General as we left the place, and as we reached a high point overlooking the town, we both turned to look at Winchester, just evacuated and now left to the mercy of the Federal soldiers. I think that a man may sometimes yield to overwhelming emotion, and I was utterly overcome by the fact that I was leaving all that I held dear on earth, but my emotion was arrested by one look at Jackson. His face was fairly blazing with the fire that was burning in him, and I felt awed before him. Presently he cried out with a manner almost savage, “That is the last council of war I will ever hold!” And it was — his first and last.

The Romney Campaign and the forced decision to leave Winchester brought out the secretiveness — and perhaps paranoia — that characterized Jackson during the rest of the Valley Campaign and many other military operations. He rarely sought advice and refused to explain his plans to his subordinates, creating potentially unnecessary leadership crises with his generals, colonels, and even staff officers.

The Confederate abandonment of Winchester raised a slough of emotions. McGuire and others who left behind family felt worried and grieved. The civilians had a mix of reactions — panic, despair, and rebellious resolve for the Southern sympathizers, relief for the Union loyalists, and some curiosity for the enslaved people who had doubtless heard rumors about possible freedom within the Union lines. But for Jackson, the retreat from Winchester prompted anger.

The Union troops who arrived in Winchester might have enjoyed their easy “victory,” but they did not yet understand that a very upset enemy general had been disconnected from a base of operations, and he was beginning to calculate his return. It would not happen immediately, and Jackson’s first attempt to regain Winchester would end in failure, but what happened in the council of war and as Jackson left the city set a emotional stage and a fierce determination that would influence the mistakes and triumphs in the coming weeks in the Shenandoah Valley in 1862.

The Valley would not be a sideshow. Instead, it would turn into an influential, costly drama that would affect the “main show” on the Peninsula and the also give rise to alarm in Washington City. However, that still lay in the future of March 11, 1862, as the Confederates left Winchester and the Union troops prepared to parade into the city for the first time. Yet perhaps the spectral words Jackson had penned earlier in March still lingered as a promise or a threat in the streets of Winchester: “Now we may look for war in earnest. . . . if this Valley is lost, Virginia is lost.”

Sources Consulted:

Alexander S. Pendleton to William Nelson Pendleton, March 6, 1862. William Nelson Pendleton Papers, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Robert Lewis Dabney, Life and Campaigns of Lieutenant General Thomas Stonewall Jackson, (Reprinted: Harrisonburg: Sprinkle Publications, 1983).

Peter Cozzens, Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008).

Robert G. Tanner, Stonewall in the Valley: Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign, Spring 1862 (New York: Doubleday, 1955).

Hunter H. McGuire, Stonewall Jackson: An Address, 1897.

2 Responses to 1862: Leaving Winchester