Farragut vs. Port Hudson

In April 1862 Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut took a fleet past Forts Jackson and St. Philip. His passage of the forts led to the fall of New Orleans and made Farragut the darling of the Northern press. In March 1863, he hoped to repeat his success at Port Hudson, Louisiana. The town had been fortified in August 1862 and along with Vicksburg, Mississippi, denied the Federals control of the Mississippi River. It also kept the two halves of the Confederacy connected. Most supplies coming in or out of Louisiana passed through Port Hudson.

Farragut was sixty-two, but in great health. He was courageous, and the men respected him but did not love him, as he was strict and at times distant. Farragut was a bit old fashioned, skeptical at times of ironclads and rifled cannon. He also hated the British due to his experiences in the War of 1812, although his ideal of an admiral was Horatio Nelson, hero of the Napoleonic Wars. He was a Tennessee native, with family connections in Louisiana, and tied by marriage to Virginia. He was hardly an abolitionist, but he was a thorough going nationalist who had served in the fleet since 1810. Although he once declared that he did not want to fight the South, he ended up doing just that.

In Late 1862 and early 1863 Farragut tested Port Hudson’s defenses with probes. This was less effective after Major General Franklin Gardner took command at Port Hudson in December 1862. Gardner added more artillery and changed the position on the river batteries to allow for better concentration of fire, he also wanted to keep the location and power of his cannon a secret, so he rarely returned fire.

Farragut had gotten along with Major General Benjamin Butler, but less so his replacement, Nathaniel P. Banks. Instead of moving on Port Hudson, Banks trained his men, rustled up horses for the cavalry, and waited on more artillery batteries to arrive. He also sent scouts to the west bank to see about bypassing Port Hudson altogether, but the area was too flooded. Farragut grew impatient, and declared: “The time has come, there can be no more delay. I must go—army or no army.”[1] Farragut also might have wanted to stun the people of New Orleans. After a meeting with Banks in St. Charles Hotel, Farragut was jeered, one person yelling “You’ll never take Port Hudson! They’ll see you to the grave!” He then boarded a streetcar only to have a woman spit in his face after he complimented her child.[2]

The plan was for Banks, with 15,000 men from XIX Corps to demonstrate against Port Hudson and attack if there was an opening. Farragut would then run the guns as he had done at New Orleans. His warships would then blockade the Red River. With that accomplished, Port Hudson would be cut off from its main source of supplies. Also, communications could be opened with Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee, then operating against Vicksburg. Banks would be free to aid Grant and possibly take command, since he out-ranked Grant.

The warships and soldiers massed at Baton Rouge. At a party, Farragut uncorked champagne and made clear his disgust with recent Union reverses along the Mississippi. When Banks showed some misgivings about the plan, Farragut responded: “What matters it, General, whether you or I are killed or not. We came here to die. Many a brave man will fall at Port Hudson.”[3]

On March 12, a grand review was held by Banks. The next day Banks headed north to Port Hudson. It was a tough march for the green soldiers. Many fell out and others stopped to plunder. The terrain was difficult, and Banks’s maps were poor. It was clear Banks would not be in position to demonstrate against Port Hudson. The Massachusetts soldiers yelled when Banks would ride by, and he noted: “There is nothing like the cheers of a soldier to stir a man’s blood.”[4] However, much of XIX Corps had yet to embrace Banks. He looked the part of a soldier and he was brave, but his record in Virginia was poor. He also lacked a common touch, and his inspirational speeches rang hollow when he spoke with the men.

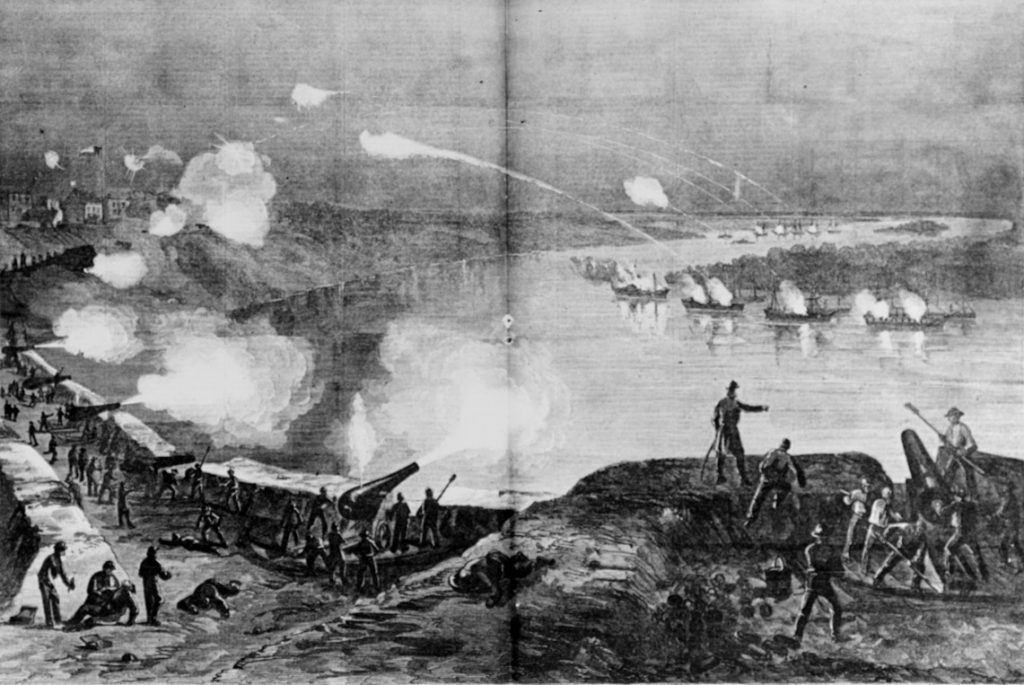

Farragut’s fleet was in position just south of Port Hudson on March 13. He had the sloops-of-war USS Hartford, Richmond, and Monogahela and the aged steam paddle-frigate USS Mississippi, the vessel used to open Japan in 1853. The smaller gunboats USS Albatross, Genesee, and Kineo were tied to each ship on the port (left) side, which faced the empty west bank. The idea was the gunboats would be somewhat shielded from gunfire and could help drag along the sloops, particularly if they took damage. Only Mississippi received no help. Ironclad USS Essex and the gunboat USS Sachem would stay behind to guard Federal transports and mortar boats, which shelled Port Hudson.

Due to the difficult march, Banks was out of position and could hardly aid Farragut by the night of March 14. When it was suggested he should attack anyway, Banks replied “I do not mean to lead my men to a fool’s fight and a dog’s death.”[5] It was wise. Gardner had as many men as Banks and hoped the Federals would attack. He would then counterattack. However, morale in XIX Corps dipped. Colonel Richard B. Irwin of Banks staff wrote that the corps was “little more than spectators and auditors of the battle between the ships and the forts.”[6]

Farragut moved ahead for fear the Rebels knew his plans and on false intelligence that a small fleet of gunboats were at Port Hudson and vulnerable. They were actually transports unloading supplies. Farragut’s fleet advanced at 10:00 p.m. At 11:20, a Rebel lookout on the west bank signaled the Confederates. The southern section of river batteries opened up. The cannon were few though, and most of the rest remained silent.

Farragut hoped the cover of darkness would spare his fleet. Yet, on the west bank trees were lit on fire and his ships were illuminated. It likely did not aid the Confederates much, as smoke and night enveloped their cannon. That said, the fire certainly made the Union sailors feel vulnerable and smoke obscured their vision. Meanwhile, the Confederate steamers at Port Hudson fled, some of them still loaded with cargo.

Early in the fight Farragut tripped and nearly fell off Hartford into the river, but was saved by his son Loyall. In the exchange of fire Loyall ducked. Farragut grabbed his boy by the shoulder and said “Don’t duck, my son, there is no use trying to dodge God Almighty.”[7] When the crew suspected a Rebel ram was bearing down, Farragut grabbed a sword and said “I am going to have a hand in this myself.”[8] The ram was illusionary, and the Hartford, with Albatross strapped to it, steamed ahead, reaching safety after midnight. It appeared Farragut had beaten Port Hudson.

The Rebels adjusted their cannon and gave Richmond, the second ship in line, a pounding. In the screams, the boatswain’s mate yelled “Don’t give up the ship, lads!” after a cannonball took both of his legs.[9] Engine damage forced the ship back, which ran aground on the west bank. Her consort, Genesee, avoided damage until then, but a shot went straight through, hitting an artillery shell. The vessel nearly burned up. Neither ship would make it past Port Hudson.

The third vessel, Monongahela, ran aground and was hit for half an hour, although it received less damage than Richmond. However, Kineo managed to break free of the shore and helped get Monongahela off the west bank. Then the engine went out. The ship drifted downstream, saved only by the Rebels’ inability to depress their cannon. The vessel drifted away, as other Confederates held back so as not to damage a ship they hoped to capture.

Mississippi took little fire, but did run aground on the west bank near Monongahela. Mississippi took heavy fire but Captain Melancton Smith remained calm, lighting a cigar with steel and flint. To Lieutenant George Dewey, he said “Well, it doesn’t look as if we could get her off.” Dewey concurred and the order to abandon ship was given. There was no panic though, and Mississippi continued to fire at Port Hudson, while the crew evacuated. Dewey, who served in the navy for decades after and won the 1898 battle of Manila Bay, called it “the most anxious moment of my career.”[10] Dewey and Smith were the last off the vessel, with Smith throwing his sword into the river, lest he be captured. It was wise, as Confederate cavalry scooped up thirty-seven of his crew.

A cheer rose up from Port Hudson as Mississippi burned up. When it floated downstream the blaze ignited some of the cannon’s friction primers, and the ship fired a final salvo at Port Hudson. From the west bank, the survivors boarded Essex and from there to Sachem. The vessels had to dodge Mississippi as it made its way down the river. Then, just before dawn, the Mississippi exploded with a deafening roar. It was so loud much of the 48th Massachusetts fled for Baton Rouge. Captain Homer B. Sprague of the 13th Connecticut recalled “The stars sank in an ocean of flame.”[11]

Dewey would write that he “lived five years in an hour” at Port Hudson.[12] As far away as the outskirts of New Orleans, the blaze of 100 cannon could be heard. Sarah Morgan, who lived nearby, wrote “Baton Rouge was child’s play compared to this.”[13] In the battle, Mississippi was lost, and three vessels suffered heavy damage. Killed, wounded, and captured totaled 113. The Confederates only lost twenty-five men. Lashing the gunboats was a wise decision that shielded them from fire and each ably supported their charges. Any other arrangement would have likely seen heavier losses on an already melancholy night.

On March 15, Banks withdrew. He explained to the men that Farragut had gotten past the cannon. Instead, Banks’ words “The object of the expedition has been accomplished” became army slang for defeat dressed as victory.[14] The men sang songs mocking Banks and cheers were absent even in the Massachusetts regiments. In addition, a terrible thunderstorm made the march back to Baton Rouge far harsher than the confident advance of March 13. Colonel Halbert Stevens Greenleaf, commander of the 52nd Massachusetts wrote: “I do not believe our great ancestor, Noah, ever saw a greater flood.”[15]

Farragut meanwhile reached Bayou Sara above Port Hudson and the small Confederate garrison fled the ruined town. When the Federals landed, an old man offered Farragut’s men good surrender terms. He was apparently serious and a marine told him they would never surrender to a bunch of traitors. When they left, the sailors were jeered by Confederates who had hidden away, one yelling “Farragut is our prisoner.”[16] Of course he was not, but for Farragut the period was a low point and he certainly felt like a prisoner caught between Port Hudson and Vicksburg. He blamed Banks, thinking he should have attacked Port Hudson. Farragut incorrectly thought Banks had more men than Gardner, concluding: “The rebels can beat us at that game of lying, so they beat us in the campaign.”[17]

Farragut threw a wine bottle in the river with a note reporting he was safe. It was found days later at Donaldsonville. To his credit, Banks remained at Baton Rouge, intent on making contact with Farragut and raiding the area east of Baton Rouge to ensure the Rebels could not use it as a staging ground. While his men devastated the region, no direct contact could be made with Farragut. Banks gave up on March 25.

Despite Farragut getting two ships across and Banks’ raids, Confederate morale was high. They had defeated most of Farragut’s fleet. While Banks had not attacked as Gardner hoped, his retreat back to Baton Rouge was treated as another, if less impressive, victory. When Farragut pushed towards Vicksburg, supplies were moved from the Red River to Port Hudson before Farragut could return.

After making contact with Grant, Farragut was reinforced by the ram USS Switzerland, although the USS Lancaster sank before the guns of Vicksburg. With Switzerland, Farragut closed off the Red River in April. Commander David Dixon Porter beamed that the closing was “death to these people.”[18] Yet, while the flow of supplies from the Trans-Mississippi did decrease, Port Hudson remained defiant. Unlike New Orleans, it would take months of bloody fighting and the longest siege of the Civil War to secure Port Hudson and the Mississippi River.

[1] A.T. Mahan, Admiral Farragut (New York, 1901), 211.

[2] David C. Edmonds, The Guns of Port Hudson: Volume One, the River Campaign (Lafayette, LA, 1983), 20.

[3] Ibid., 38

[4] Ibid., 59

[5] James G. Hollandsworth Jr. Pretense of Glory: The Life of General Nathaniel P. Banks. (Baton Rouge, 1998), 104.

[6] Richard B. Irwin, “The Capture of Port Hudson,” in Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, ed., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), 3:590.

[7] H.D. Smith, “With Farragut on the Hartford,” in Under Both Flags (Guilford, CT, 2003), 33.

[8] Ibid., 34.

[9] Lawrence Lee Hewitt, Port Hudson: Confederate Bastion on the Mississippi (Baton Rouge, 1994), 71.

[10] George Dewey, Autobiography of George Dewey: Admiral of the Navy (New York, 1913), 96.

[11] Homer B. Sprague, History of the 13th Infantry Regiment of Connecticut Volunteers During the War of the Rebellion (Hartford, 1867), 103-104.

[12] Dewey, Autobiography of George Dewey, 85.

[13] Sarah Morgan Dawson, A Confederate Girl’s Diary (Bloomington, 1960), 337-338.

[14] Edmonds, The Guns of Port Hudson, 150.

[15] John Farwell Moors, History of the Fifty-Second Regiment: Massachusetts Volunteers (Boston, 1893), 81.

[16] Edmonds, The Guns of Port Hudson, 162.

[17] Ibid., 217.

[18] Donald S. Frazier, Thunder Across the Swamp: The Fight for the Lower Mississippi, February 1863 – May 1863, (Buffalo Gap, TX, 2011), 142.

Enjoyable read.

I feel like I read three well written articles not one. Thanks.

I had to look up how a man born in 1801 could have strong feelings for the British based on the War of 1812. Wikipedia helped:

“:..Farragut … was added to the U.S. Navy’s rolls with the rank of boy in the spring of 1810. Through the influence of his foster father, [David Porter!] Farragut was commissioned a midshipman in the U.S. Navy on December 17, 1810, at the age of nine…” So the man was in the navy when the British were impounding Americans for service and fought them.

Farragut was the embodiment of the navy by the time 1861 rolled around, much as Scott was for the army. Honestly, I also think they were the best commanders of their service this country has yet produced.

Great article!

I think the flooding on the west bank in Pointe Coupee Parish, across from Port Hudson, was caused by the Confederates purposefully breaching the levee to flood the river road so to protect Port Hudson from being taken in reverse, as Grant was doing to Vicksburg.

That is exactly what they did and it worked well. Yet, Banks could not have pulled a Grant by short hand. Transports could not run the cannon at Port Hudson. So he cleared out Bayou Teche. That accomplished, he could then move on Port Hudson.