Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet in Chattanooga, Part I

ECW welcomes guest author Ed Lowe

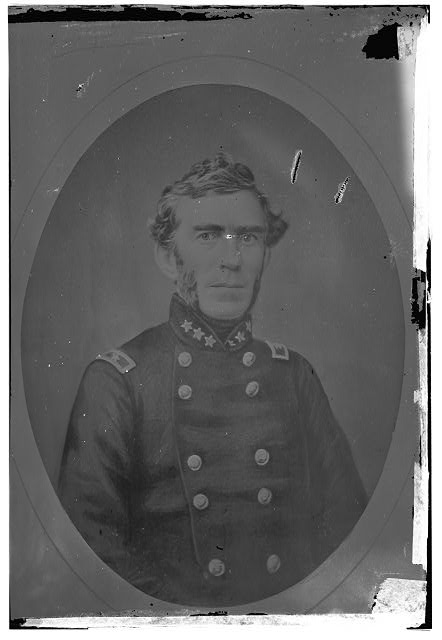

The Confederate victory at Chickamauga, Georgia, in September 1863 offered up a further opportunity for General Braxton’s Bragg Army of Tennessee to finish off Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland. Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, gaining the name, “Bull of the Woods” after Chickamauga, spearheaded the pursuit of Rosecrans’s army as the Federals occupied Chattanooga, Tennessee. Longstreet and two divisions from General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had journeyed south in early September. His reinforcements to Bragg’s army were key to the victory in northern Georgia, a victory not complete unless Bragg could retake the vital city of Chattanooga.

Chattanooga was strategically important to both sides with its railroad networks. Three railroads connected in Chattanooga. The Western & Atlantic ran from Chattanooga to Dalton, Georgia, and then further south into the state. The Nashville & Chattanooga traversed out of Chattanooga to Stevenson, Alabama before turning sharply toward Nashville. The Virginia & Tennessee ended its journey at Chattanooga, a key spoke in the wheel connecting Virginia and other Eastern states with states farther west. With Rosecrans embedded in Chattanooga, Bragg could position his soldiers on the dominant terrain surrounding Chattanooga. Bragg could shape future operations to destroy Rosecrans’s army and bring the city back under Confederate control.

The Tennessee River snaked around the north side of Chattanooga, continuing its journey west and veering into Alabama. Casting shadows across the river around Chattanooga was the towering fortress of Lookout Mountain, rising 2,000+ feet. Farther east was the long ridgeline known as Missionary Ridge, which one Northern correspondent described as “an everlasting thunderstorm that will never pass over.” Nestled under both features was Chattanooga, with a modest population of 2,500 citizens. With Bragg occupying these heights, he relied heavily on Longstreet to keep vital supplies from reaching Rosecrans. However, lack of communication and stubbornness by Longstreet disrupted Confederate plans to starve Rosecrans into submission or force him to withdraw from the city.

Rosecrans occupied the towering and rocky Lookout Mountain after his defeat at Chickamauga; however, he relinquished control of the mountain to Bragg, much to the chagrin of his subordinates who saw it as a favorable defensive position. On the 8th of October, Bragg directed Longstreet’s 12,000 veterans to occupy the Confederate’s left flank, around Lookout Mountain, covering Lookout Valley to the west. Longstreet had with him two stout divisions of Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws and Brig. Gen. Micah Jenkins (the latter formerly under command by Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood).

Jenkins had assumed command from Brig. Gen. Evander Law shortly after the battle of Chickamauga. Of note, Law had led the division since Gettysburg, taking over after Hood’s wounding on July 2, 1863, and then again after Hood’s wounding at Chickamauga. Jenkins and Law were both South Carolinians and educated at what is now The Citadel. With soldiers strongly attached to Law, Jenkins assuming command caused consternation amongst the veterans. These ill feelings within Hood’s old division plagued Longstreet for months.

Taking command in June 1862, Bragg led the army through a series of battles in Kentucky and across middle and eastern Tennessee. Though victorious at Chickamauga, the battle had left Bragg frustrated, the victory incomplete. Shortly after Chickamauga, Bragg took administrative action against two senior commanders, Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk and Maj. Gen. Thomas Hindman for perceived errors during the campaign. And the Bragg and Polk squabbling dated back months even before Chickamauga, which proved the final straw for Bragg. His chief of staff, Brig. Gen. William Mackall, confessed that Bragg “is very earnest at his work, his whole soul is in it, but his manner is repulsive and he has no social life. He is easily flattered and fond of seeing reverence for his high position.” This was the environment that Longstreet had stepped into upon his arrival on September 19, and he quickly sided with the anti-Bragg faction.

Whether intended or not, the senior lieutenant general in Bragg’s army, James Longstreet, became the de-facto leader of the faction. Lafayette McLaws said Longstreet became “the nominal head of [the] cabal.” Just days removed from Chickamauga, Longstreet wrote to Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon expressing a lack of confidence in Bragg’s abilities. As the Confederate army prepared for the next phase against Rosecrans, Longstreet pleaded with Seddon that “I am convinced that nothing but the hand of God can save us or help us as long as we have our present commander.” Longstreet even urged Confederate authorities in Richmond to send General Robert E. Lee south. This request failed to convince Richmond. As September gave way to October 1863, Bragg’s frustrated commanders increased their correspondence with Richmond.

A dozen of Bragg’s generals, including Longstreet, signed a petition prepared for the Confederate President, Jefferson Davis, recommending Bragg’s removal from command. Shouldering dissatisfaction from his senior commanders, President Davis presented a strong countenance in favor of Bragg, however. Bragg hoped that the president might intervene on his behalf. Davis dispatched a trusted aide, Colonel James Chesnut to Tennessee to evaluate the situation. Dismayed at what he saw and heard, it was not long before Chestnut wired Davis that “your immediate presence in this army is urgently demanded.” And so, on the 6th of October, President Davis departed for Chattanooga from Richmond.

Meeting in Bragg’s office on October 9, Davis met with the four highest-ranking officers in Bragg’s command, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, Maj. Gen. Simon Buckner, Lt. Gen. D.H. Hill, and Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham, with Bragg present, sitting in the corner. All recommended removing Bragg from command. Meeting with other officers who supported Bragg and those advocating his removal over the next couple of days, Davis kept Bragg in command. As President Davis set his departure from Chattanooga on October 14, he complimented Bragg for his recent victory at Chickamauga and sent a warning to Bragg’s senior officers, “he who sows the seeds of discontent and distrust prepares the harvest of slaughter and defeat.” Meanwhile, Longstreet wrestled with keeping secure the terrain west of Lookout Mountain or at least disrupting Union supply efforts into Chattanooga.

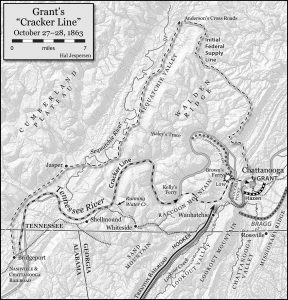

Longstreet biographer, Jeffrey Wert, pointed out simply occupying Lookout Mountain alone was not enough to hamper Union supplies. “That could only be accomplished by Confederate infantry stationed in the [Lookout] valley,” Wert underscored. Longstreet directed Law, a brigade commander now with Jenkins leading the division, into the valley. Law positioned the 4th and 15th Alabama Infantry Regiments to picket the river and kept his other three regiments in reserve. With some soldiers armed with the accurate English Whitworth Rifles, the Alabama soldiers shut down the Union supply route into Chattanooga, which ran close to Lookout Mountain. Picking off mules along the route, one Confederate soldier observed that they were able to “shoot down the front teams, which after being done, the road was entirely blocked.” Rosecrans would have to look for an alternate route; however, his actions only made it harder to feed and supply his men and horses.

The new Union route was an arduous 60-mile path from the main supply depot at Bridgeport, Alabama over Walden’s Ridge. Yet, “Rosecrans was so preoccupied with the details of fortification and reorganization,” historian Wiley Sword commented, “that initially little was done to resupply the army.” It could take days for wagons to make the haul from Alabama into Chattanooga with the roads badly damaged by heavy rains. Known for his valiant stand on Horseshoe Ridge at the battle of Chickamauga, allowing Rosecrans’s army to safely withdraw to Chattanooga, Maj. Gen. George Thomas of the Union army confessed to his wife, “one of three things had to be done—open the river, retreat, or starve.” Rosecrans was quickly running out of options to maintain the army. Superiors in Washington, D.C. were losing confidence in his abilities to hold Chattanooga.

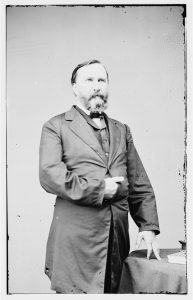

Graduating from West Point in 1842 in a crowd of future Civil War generals, Longstreet observed a cadet in the following year’s class who, as he remembered in his memoirs, “was to eclipse them all.” That man, of course, was Ulysses S. Grant. To Longstreet Grant was “of noble, generous heart, a lovable character, a valued friend.” Longstreet and Grant served together in their initial assignments at Jefferson Barracks, just south of St. Louis. Over time they collected a healthy respect for each other’s abilities. On opposing sides now with the war in full throttle, authorities in Washington, D.C. sent Maj. Gen. Grant west to Chattanooga to assume command of U.S. forces in the area. Aggressive and offensive-minded, the arrival of his old friend into the city on October 23 would test Longstreet’s ability to maintain effectiveness in the Lookout Valley. And Longstreet’s already tense relationship with Bragg continued to decline.

————

COL (ret) Ed Lowe served 26 years on active duty in the U.S. Army with deployments to Operation Desert Shield/Storm, Haiti, Afghanistan (2002 & 2011), and Iraq (2008). He attended North Georgia College and has graduate degrees from California State University, U.S. Army War College, U.S. Command & General Staff College, and Webster’s University. He is currently an adjunct professor for the University of Maryland/Global Campus & Elizabethtown College, where he teaches history and government. He is currently working on two books for Savas Beatie. The first covers Longstreet’s First Corps from Gettysburg to East Tennessee, and the second is an Emerging Civil War Series book on Longstreet’s East Tennessee Campaign. He is married with two daughters and lives in Ooltewah, Tennessee. He currently serves as President of the Chickamauga & Chattanooga Civil War Round Table, reconstituted in September of 2020.

Suggested Readings

Longstreet, J. (1984). From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America. Blue and Grey Press.

Mendoza, A., & And, F. (2008). Confederate Struggle for Command: General James Longstreet and the First Corps in the West. Texas A & M University Press.

Sword, W. (1995). Mountains Touched with Fire: Chattanooga besieged, 1863. St. Martin’s Press.

Wert, J. D. (1994). General James Longstreet: the Confederacy’s most controversial soldier: a biography. Simon & Schuster.

Woodworth, S. E. (1998). Six armies in Tennessee: the Chickamauga and Chattanooga campaigns. University Of Nebraska Press.

The Union forces might have been able to save themselves a lot of blood and effort if only they had allowed the Confederate army commanded by Bragg to self-destruct from the back-biting factions within it, or so it sometimes seems. Geezz, what a cluster-you-know-what.

Douglas—It was seemingly close to self-destruction indeed. Thank you for the comment. Ed