Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet in Chattanooga, Part III

ECW welcomes back guest author Ed Lowe

General Braxton Bragg, commander of the Army of Tennessee, elected to make a significant organizational change in his army, especially after the failed effort at the battle of Wauhatchie. That something turned out to be sending Longstreet’s First Corps north to tackle Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s small Army of the Ohio, situated around Knoxville to the north. Bragg was all too eager to be rid of Longstreet’s services. The two had verbally jousted since Longstreet joined the Army of Tennessee just in time for the September battle of Chickamauga.

From a tactical and operational perspective, however, was that the wisest course of action for Bragg to take? Bragg had initially dispatched the division of Maj. Gen. Carter Stevenson in the direction of Knoxville, followed by Benjamin F. Cheatham’s division. As Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s increased his strength in personnel, Bragg deploying 12,000 men from his command in Chattanooga would only widen the gap with Grant’s growing numbers.

Authorities in Richmond applied pressure to Bragg that he undertakes some offensive operation before Grant fully concentrated his forces in Chattanooga. Burnside’s small army in Knoxville seemed a suitable objective. As historian Earl Hess pointed out, once the Confederates occupied that part of East Tennessee, “a rebel force could invade middle Tennessee or Knoxville.” Still, removing 12,000 hardened veterans hardly seemed a prudent course of action. “This was a particularly foolish dispersion of force,” wrote historian Craig Symonds. Nonetheless, Bragg and Davis plowed ahead sending Longstreet north. As historian Wiley Sword commented, Bragg executed dispatching Longstreet north “on the basis of political expediency without due regard to the practical consequences.” Earl Hess in his biography of Bragg noted moving Longstreet into East Tennessee made sense only if he could defeat Burnside and “return to Bragg before Sherman reach[ed] Grant. Such a victory would boost morale and reopen the heart of East Tennessee to the Confederates.”

Bragg already had around 13,000 men in East Tennessee, in the divisions of Maj. Gen’s Stevenson and Cheatham, plus two other brigades. Once deployed, Longstreet took with him his two divisions, plus Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s robust cavalry division of 5,000 troopers. Upon Longstreet’s deployment north, both Stevenson and Cheatham returned to Chattanooga (Cheatham had been working jointly with Stevenson since the end of October). However, all the shuffling around proved a net loss in force structure to Bragg by 7,200 men. The disparity in troop strength varies amongst historians between what Bragg was left with and what Grant inherited and would later receive. What is not disputed is that Bragg was greatly outnumbered. An oft-quoted line from Grant’s memoirs provides a summation on his thoughts about Confederate strategy: “Jefferson Davis had an exalted opinion of his own military genius…On several occasions during the war he came to the relief of the Union Army by means of his ‘superior military genius.’” For Bragg’s maneuvering and concept of operations, it only spelled doom for the Army of Tennessee.

Longstreet offered a different course of action to Bragg upon hearing about the proposed movement of his corps toward Knoxville. Perhaps leaving the siege lines in Chattanooga and falling back behind the Chickamauga Creek while “sending a strong force for swift march against General Burnside – strong enough to crush him – and returning to Chattanooga before the army under General [William T.] Sherman could reach there,” Longstreet wrote in his memoirs. When Bragg stood firm on his commitment to send Longstreet away, Longstreet warned the operation “would consume so much time that General Grant’s army would be up, when he would organize attack that must break through the line before I could return to him. [Bragg’s] sardonic smile seemed to say that I knew little of his army or of himself in assuming such a possibility.” With that, Longstreet prepared his force for operations against Burnside.

Problems abounded for Longstreet and his men as they traveled from Chattanooga. The comical inefficiency of the rail system did not get the movement off to a confident start. Soldiers had to disembark from the train when it reached an incline, march to the top of the hill and then reboard the train before continuing the journey. Longstreet had little knowledge of the area of operations, and having few maps only worsened his situational understanding. Longstreet arrived at Sweetwater on November 9 where he received even more ominous news. Maj. Gen. Stevenson’s division was recalled back to Chattanooga, along with supplies they had collected.

Back and forth accusations illuminated the communications between Bragg and Longstreet during that second week in November. Transportation and supply challenges weighed heavily between the two commanders. As Longstreet recalled in his memoirs, “It began to look more like a campaign against Longstreet than against Burnside.” These difficulties aside, Longstreet conducted operations around Loudon and Lenoir’s Station November 13-15, 1863.

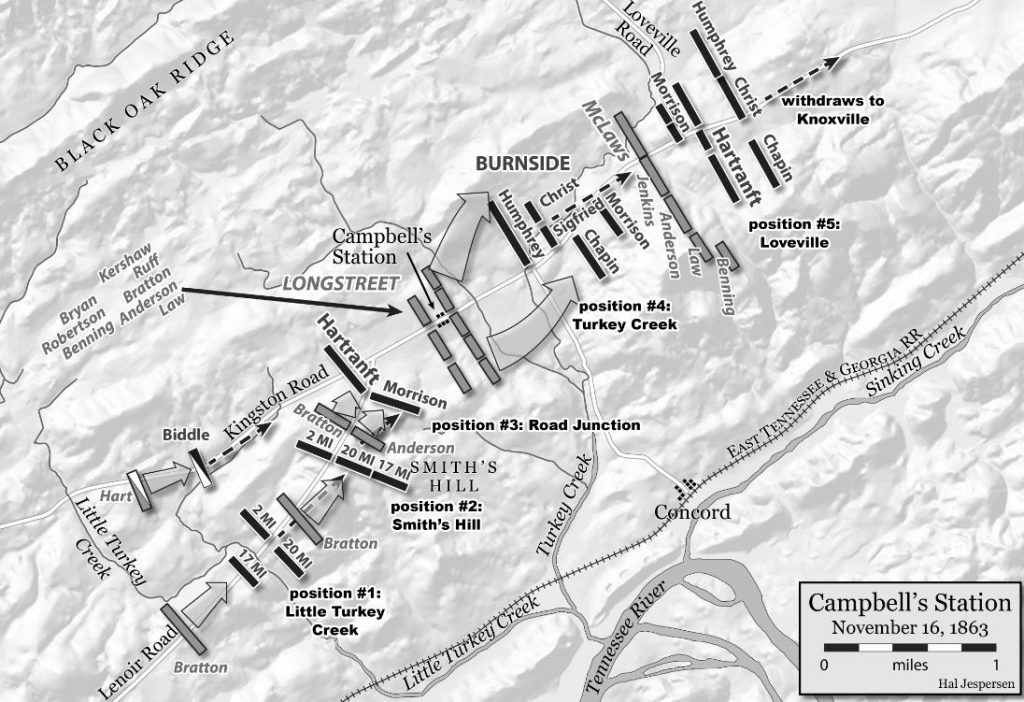

As historian Earl Hess explained, “Burnside was determined to get a head start on Longstreet by evacuating Lenoir’s Station during the night of November 15 and then securing the vital road junction at Campbell’s Station on his way to Knoxville.” Campbell’s Station lay just 17 miles from Knoxville. Grant recognized the importance of this moment, often being retold by authorities in Washington about East Tennessee’s value. “It is of the most vital importance that East Tennessee should be held,” Grant strongly reminded Burnside on November 14. “Take immediate steps to that end.”

While Burnside could have strongly resisted Longstreet’s river crossing at Loudon, he chose a different strategy. As he recorded in his official report, Burnside wrote, “Knowing the purpose of General Grant as I did, I decided that he could be better served by driving Longstreet farther away from Bragg than by checking him at the river, and I accordingly decided to withdraw my forces and retreat leisurely toward Knoxville, and soon after daylight on the 15th the whole command was on the road.” The key, however, was reaching the road junction at Campbell’s Station first.

Moving parallel to the river, the division of Brig. Gen. Micah Jenkins followed the Union withdrawal along the Lenoir Road. Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws followed with his division to the north, along the Kingston Pike. By most accounts, Burnside’s men reached the intersection just minutes before McLaws arrived. Labeled as a battle of mostly “artillery combat,” Burnside slowly withdrew his forces. As Longstreet described it, “Before other combinations suited to our purpose could be made it was night, and the enemy was away on his march to the fortified grounds about Knoxville.”

For the rest of November Longstreet engaged in siege-like operations around Knoxville. This came to an end at his failed assault on Fort Sanders on November 29, 1863. With intelligence that reinforcements were approaching and that Chattanooga had fallen to Grant, Longstreet moved further to the northeast, closer to Virginia. There, Longstreet would remain through the winter and into spring, before rejoining Lee at the end of April, just in time for the battle of Wilderness in early May.

————

COL (ret) Ed Lowe served 26 years on active duty in the U.S. Army with deployments to Operation Desert Shield/Storm, Haiti, Afghanistan (2002 & 2011), and Iraq (2008). He attended North Georgia College and has graduate degrees from California State University, U.S. Army War College, U.S. Command & General Staff College, and Webster’s University. He is currently an adjunct professor for the University of Maryland/Global Campus & Elizabethtown College, where he teaches history and government. He is currently working on two books for Savas Beatie. The first covers Longstreet’s First Corps from Gettysburg to East Tennessee, and the second is an Emerging Civil War Series book on Longstreet’s East Tennessee Campaign. He is married with two daughters and lives in Ooltewah, Tennessee. He currently serves as President of the Chickamauga & Chattanooga Civil War Round Table, reconstituted in September of 2020.

————

Sources

Cozzens, Peter (1996). The Battles for Chattanooga: The shipwreck of their hopes. University of Illinois Press.

Daniel, Larry (2019). Conquered: Why the Army of Tennessee failed. University of North Carolina Press.

Hess, Earl (2016). Braxton Bragg: The most hated man of the Confederacy. University of North Carolina Press.

—. (2012) The Civil War in the West: Victory and defeat from the Appalachians to the Mississippi. University of North Carolina Press.

—. (2012). The Knoxville Campaign: Burnside and Longstreet in East Tennessee. University of Tennessee Press.

Longstreet, James (2004). From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America. Reprint. Barnes & Noble.

Peterson, Larry (2018). Decisions at Chattanooga: The nineteen critical decisions that defined the Battle. University of Tennessee Press.

Stoker, Donald (2012). The grand Design: Strategy and the U.S. Civil War. Oxford University Press.

Sword, Wiley (1995). Mountains touched with fire: Chattanooga besieged, 1863. St. Martin’s Press.

Thomson, Brian, ed., (2002). The Civil War memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

U.S. War Department (1880-1891). The war of the rebellion: A compilation of official records of Union and Confederate armies. 128 vols. Washington, DC.

White, Ronald C. (2016). American Ulysses: A life of Ulysses S. Grant. Random House.

Once Grant & Hooker arrived and opened the supply line there was no path to victory for the Confederates. A waste of any opportunity that may have existed after Chickamauga.

The day after Longstreet had Burnside holed up at Knoxville, Edward Porter Alexander felt he had good artillery positioning and readied for attack. Read his take on Knoxville, a battle where the Union strung telegraph wire from stump to stump to stump across the front of Fort Sanders, taking down the first charging row of combatants. It is said that Longstreet was a better subordinate to Lee after having gone West.

Henry, Yes, Alexander was none too pleased with how the plan changed for the 29th assault on the fort, lacking any strong artillery preparation before the assault. Good point.