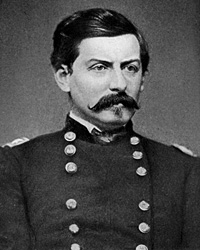

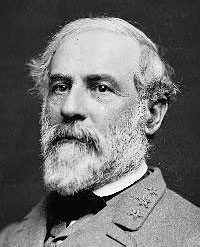

Why Did Robert E. Lee Think Highly of George B. McClellan?

When Civil War students rate the top generals of the war, Robert E. Lee and George B. McClellan can usually be found at opposite ends of the rankings. Though he has had some detractors, Lee is commonly found among the war’s best and, though he has had some proponents, McClellan’s name can usually be located towards the bottom of these fantasy lists. These exercises can generate excellent discussion of the merits of certain generals over others and what makes a good leader in wartime.

Today, we can find these debates at roundtables, blogs, websites, and more. Civil War soldiers talked among themselves about these same things, then around a campfire. While their fantasy hierarchies rarely exist from 160 years ago, pieces of them can be surmised. Indeed, a part of Robert E. Lee’s list exists in numerous accounts of the general’s conversations. Surprisingly, you could expect to find McClellan near the top of Lee’s ratings. (Pause here and let that sink in for a second.)

The most common version of Lee ranking McClellan among the war’s best—if not the best—is recorded in Robert E. Lee Jr.’s Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee, published in 1904. After the war ended, a son of one of Lee’s cousins asked the former general “which of the Federal generals he considered the greatest,” to which Lee “answered most emphatically ‘McClellan by all odds.’”[1]

Lee’s statement might not be the only thing raising your eyebrows. His assertion was recorded only in 1904, 34 years after his death, and not by the person who Lee was talking to. However, let’s not discard this story just yet. (Either way, I don’t always think we should trash a story because it was not recorded contemporarily.) A wartime letter written by a friend of McClellan’s to the general reported that his own friend had just returned from the Confederacy. While there, he supposedly heard one of Lee’s daughters exclaim, “Genl McClellan was the only Genl Father dreaded.”[2] Furthermore, on January 18, 1869, Lee said of his former Union adversary, “As regards General McClellan, I have always entertained a high opinion of his capacity, and have no reason to think that he omitted to do any thing that was in his power.”[3] Clearly, Lee praised McClellan enough for there to be substance to his assessment, and not to simply brush off Lee’s statements as tongue-in-cheek jesting or as a creation of someone’s imagination after Lee’s death. All of this begs the question then: what should be made of Lee’s respect for McClellan’s capabilities, and why did he feel that way?

After sorting through all of the times Lee talked about McClellan as a general, it appears Lee respected him in a two-fold manner. First, Lee’s respect for McClellan was rooted in the Federal general’s soft-hand approach to the war and to the Confederacy. In November 1862, upon receiving word of McClellan’s removal from command of the Army of the Potomac, Lee told Lt. Gen. James Longstreet that he regretted the change because “we always understood each other so well. I fear,” Lee continued “they may continue to make these changes till they find some one who I don’t understand.”[4] In his memoirs, Longstreet expanded upon Lee’s feelings:

When informed of the change, General Lee expressed regret, as he thought that McClellan could be relied upon to conform to the strictest rules of science in the conduct of war. He had been McClellan’s preceptor, they had served together in the engineer corps, and our chief thought that he thoroughly understood the displaced commander. The change was a good lift for the South, however; McClellan was growing, was likely to exhibit far greater powers than he had yet shown, and could not have given us opportunity to recover the morale lost at Sharpsburg, as did Burnside and Hooker.[5]

Historian Ethan Rafuse wrote, “McClellan and Lee shared a common understanding of the strategic, organizational and operational dynamics of the Eastern Theater and the war in general. It was this shared understanding, rather than the disparagement of his foe’s considerable abilities that was at the heart of Lee’s remarks.”[6]

Plenty of episodes during the Peninsula Campaign confirm McClellan’s and Lee’s shared understanding. During that campaign, the property of Lee’s son Rooney—White House—fell into Union hands. Lee’s wife Mary and two of their daughters were there and eventually they became trapped behind Union lines. McClellan assured Lee his property would be protected and even arranged safe escort for Lee’s family to Richmond. No doubt Lee was relieved.

Throughout the campaign, as the armies inched closer to Richmond, McClellan and Lee kept up a regular correspondence regarding the exchange of prisoners of war. The two generals established representatives from their respective commands to handle the matter and agreed that medical personnel left behind to tend wounded soldiers were not to be handled as combatants in such exchanges. Between June 18 and 21, 1862, both men even diffused a potentially nasty situation regarding the execution of prisoners and subsequent retaliatory measures that were prepared but never carried out. When it came to how the war should be conducted between two opposing forces, the two clearly understood each other well.

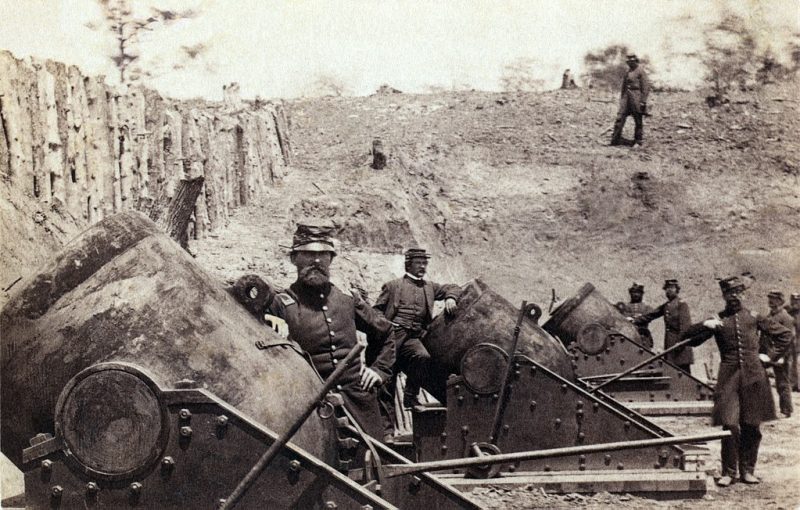

Lee’s respect for McClellan went beyond these off-the-battlefield matters, though. After the war, Lee pegged McClellan “an able but timid commander,” and the military record between the two justifies why Lee thought McClellan a capable battlefield commander.[7] At the outset of the Peninsula Campaign at the Siege of Yorktown, Lee served in Richmond at President Jefferson Davis’s side. The reports he received from Maj. Gen. Joseph Johnston on the front lines were not favorable. As the siege lines grew longer, Johnston wrote Lee, “We are engaged in a species of warfare at which we can never win. It is plain that General McClellan will adhere to the system adopted by him last summer, and depend for success upon artillery and engineering. We can compete with him in neither.”[8] In a no-win situation, Johnston pulled his army back closer to Richmond while searching for an opportunity to strike McClellan where he could not utilize his superior numbers, artillery, and engineering. Johnston launched that attack on May 31, 1862. The Battle of Seven Pines (Fair Oaks) did not produce the results Lee and Johnston hoped for. Johnston also fell wounded and Davis appointed Lee to command his army.

Four days after taking command, Lee predicted his enemy’s next step. “McClellan will make this a battle of posts,” he began. “He will take position from position, under cover of his heavy guns, & we cannot get at him without storming his works, which with our new troops is extremely hazardous. You witnessed the experiment Saturday [Johnston’s May 31st attack]. It will require 100,000 men to resist the regular siege of Richmond, which perhaps would only prolong not save it. I am preparing a line that I can hold with part of our forces in front, while with the rest I will endeavour to make a diversion to bring McClellan out.”[9] Lee worked hard “to bring McClellan out” and fight him on a fair field of battle. He did in late June and drove McClellan away from Richmond, though the results were not quite as Lee hoped. His attacks hurt McClellan’s army but did not destroy it. The ground his army won back from the Federals was won at a heavy casualty count.

In September 1862, at the beginning of the Maryland Campaign, Lee voiced his opinion of McClellan’s generalship. “He is an able general but a very cautious one.” Following the Confederate victory at Second Manassas, the Union forces under McClellan’s command were “in a very demoralized condition, and will not be prepared for offensive operations—or he will not think it so—for three or four weeks.”[10] In reality, McClellan was already moving in the direction of Lee’s army. During the campaign, Lee said McClellan’s advance was “more [rapid] than convenient” for him.[11] After the campaign, Lee expressed being filled “with amazement” at the rapidity with which McClellan rallied Federal troops after Second Manassas and marched out of Washington, DC, to meet Lee in battle.[12] Ultimately, McClellan shattered Lee’s timetable of events and prevented Confederate victory in Maryland. Even days before McClellan’s removal from command, Lee was surprised by the way McClellan moved his army.[13] After McClellan’s removal, Lee had a new adversary to learn.

Unfortunately, Robert E. Lee never expanded upon his statements about McClellan’s generalship; we are only left to wonder what he really meant. However, there is enough documentation to provide context to Lee’s assessment. At the end of the Civil War, McClellan did not rate highest among Union military commanders. To Lee though, he was an able opponent. The Confederate chieftain respected McClellan’s code of conduct during the conflict and McClellan’s ability to use his advantages as a commander and those of his army to make the Confederacy’s war aims difficult to achieve. McClellan showed Lee the limits of the Confederacy’s capacity to wage war. Throughout the rest of the war, Lee kept those lessons he learned in mind and sought to avoid the “battle of posts” in favor of decisive, offensive battlefield victories. Each general understood what they each needed to do to accomplish their objectives, and they each understood that doing so against one another would be no easy task.

[1] Robert E. Lee, Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee (New York: Doubleday, Page, & Company, 1904), 416.

[2] Quoted in letter to McClellan from “A Friend,” March 28, 1863, Reel 35, George B. McClellan Papers, Library of Congress.

[3] J. William Jones, Personal Reminiscences, Anecdotes, and Letters of Gen. Robert E. Lee (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1875), 238-39.

[4] James Longstreet, “The Battle of Fredericksburg,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. 3 (New York: The Century Co., 1888), 70.

[5] James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox (Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1896), 291.

[6] Ethan Rafuse, “Robert E. Lee and George B. McClellan Battled to win the War in the East,” The Courier 14, no. 5 (2010): 2.

[7] E.C. Gordon to William Allan, November 18, 1886, in Douglas Southall Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenants: A Study in Command, vol. 2 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1943), 716-17.

[8] OR, vol. 11, pt. 3, 477.

[9] Robert E. Lee to Jefferson Davis, June 5, 1862, in Clifford Downey and Louis H. Manarin, eds., The Wartime Papers of R.E. Lee (New York: Bramhall House, 1961), 184.

[10] John G. Walker, “Jackson’s Capture of Harper’s Ferry,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. 2 (New York: The Century Co., 1887), 606. It should be noted that Walker’s account suffers from factual flaws, see Joseph L. Harsh, Taken at the Flood: Robert E. Lee & Confederate Strategy in the Maryland Campaign of 1862 (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1999), 143-45.

[11] Robert E. Lee to Jefferson Davis, September 16, 1862, in Dowdey and Manarin, eds., Wartime Papers, 309.

[12] Garnet Joseph Wolseley, “A Month’s Visit to the Confederate Headquarters,” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, January 1863, 18.

[13] OR, vol. 19, pt. 2, 698.

Very interesting article. Is it fair to question Lee’s judgement on this subject? His judgement certainly has been questioned and even trashed concerning other things, depending of course on who was or is making the evaluation(s). Gettysburg certainly comes to mind. Lee appeared to get the best of Grant on some occasions between The Wilderness and Appomattox, yet Grant always maintained the initiative. He kept the pressure on Lee, and as commander of all Union forces kept much of the Confederacy under the gun. Lee bested McClellan to keep Richmond safe, and though defeated at Antietam, he was able to keep his army intact in Maryland despite McClellan having the fabled Special Order 191 in his possession. Could Lee rating McClellan so generously be a matter of sour grapes on his part concerning Grant? His and Longstreet’s musings about him center on “understanding” him, and each other. Yet Lee described McClellan as “cautious”. So it comes across (to me) that Lee “preferred” McClellan as an opponent.

When everything is looked at in context, I think this is a fair assessment. The fact is that Lee drove McClellan from a position on the doorstep of Richmond to Harrison’s Landing, some 25 miles distant and – but for the ball being dropped by Jackson, Huger, and Holmes – came close to cutting McClellan’s army in two on June 30. I note that while the post mentions the cost to Lee of doing this, Leon Tenney in his 2012 self-published book makes a good case that McClellan’s casualties were higher than historically assumed and were virtually equal to Lee’s, even though McClellan spent the week on the defensive. At Antietam, while Lee had been forced to the brink on September 17, he actually was considering renewing the offensive on September 18 and was talked out of it by Stonewall Jackson – hardly a sign of respect for McClellan. We should not forget that in April 1862 Lee received correspondence from Johnston (McClellan’s old army friend) that was disparaging of McClellan’s failure to assault the Warwick Line. Lee also praised Meade at the time he learned that Meade had replaced Hooker during the Gettysburg Campaign. In short, I would not make too much of these statements (mostly hearsay) – at least so far as they purport to be Lee’s opinion of McClellan on the battlefield.

Others in the North and the South had a high opinion of McClellan, although Grant considered McClellan to be one of the “mysteries” of the war. If, however, you consider that McClellan apparently had not even been reappointed to the command of the Army of the Potomac (or so I read once) when he rallied it and led it through the Battle of Antietam, and thought he could face a court martial if he lost the battle, you have to respect the man for his courage and service.

Thanks to Kevin Pawlak for presenting another facet of the disappointment that we now recognize as Major General McClellan. [The worst “compliment” which can be given a West Point grad today: “You have an attribute reminiscent of McClellan.”] Attempts have been made, and are ongoing, to figure out, “What went wrong with George McClellan?” Perhaps it was a perfect storm: 1) Overly reliant on preparation; 2) Meddling and interference by President Lincoln; 3) Impatience and arbitrary deadlines of President Lincoln; 4) Arrogance and over-confidence of George McClellan; 5) Typhoid fever: the same illness that killed Lincoln’s son, Willie, in FEB 1862 made McClellan bedridden a month or two earlier… and likely delayed plans for a Spring offensive.

Perhaps the best assessment of McClellan is Grant’s (mentioned by Taylor in the comment, above): “He was a mystery.”

Lee was a commandant of West Point and after the war led Washington College. If I were able to ask him on the subject, I’d ask Lee if he respected how McClellan trained/organized his raw Union recruits.

I appreciate this sympathetic look at McClellan. It does put Lee’s assessment in context.

After admitting McClellan was a mystery, Grant also said: “I have never studied his campaigns enough to make up my mind as to his military skill, but all my impressions are in his favor…the test which was applied to him would be terrible to any man, being made a major-general at the beginning of the war. It has always seemed to me that the critics of McClellan do not consider this vast and cruel responsibility- the war a new thing to all of us, the army new, everything to do from the outset, with a restless people and Congress. McClellan was a young man when this devolved upon him, and if he did not succeed, it was because the conditions of success were so trying. If McClellan had gone into the war as Sherman, Thomas, or Meade, had fought his way along and up, I have no reason to suppose that he would not have won as high a distinction as any of us.”

In the interests of full disclosure, the rest of the quote attributed by Young to Grant is as follows:

“McClellan’s main blunder was in allowing himself political sympathies, and in permitting himself to become the critic of the President, and in time his rival. This is shown in his letter to Mr. Lincoln on his return to Harrison’s Landing, when he sat down and wrote out a policy for the government. He was forced into this by his associations, and that led to his nomination for the Presidency. I remember how disappointed I was about this letter, and also in his failure to destroy Lee at Antietam”

I’m curious as to why you omitted this – especially the last sentence, in light of the subject matter of your well-written book.

Asked then who was the ablest Federal general he had opposed throughout the war, Robert E. Lee replied without hesitation: “McClellan, by all odds.”

From what I could find on the Internet, that quote could be wrongly attributed to Lee:

Quote:

(10) In 1867 John Singleton Mosby, was interviewed in the Philadelphia Post about the merits of the different generals in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Whom do you consider the ablest General on the Federal side?” “McClellan, by all odds. I think he is the only man on the Federal side who could have organized the army as it was. Grant had, of course, more successes in the field in the latter part of the war, but Grant only came in to reap the benefits of McClellan’s previous efforts. At the same time, I do not wish to disparage General Grant, for he has many abilities, but if Grant had commanded during the first years of the war, we would have gained our independence. Grant’s policy of attacking would have been a blessing to us, for we lost more by inaction than we would have lost in battle. After the first Manassas the army took a sort of ‘dry rot’, and we lost more men by camp diseases than we would have by fighting.”

Mosby made the statement, NOT Lee according to this source. The ones who claim Lee said it say he said it in 1870, so since Mosby said it earlier, perhaps Lee was referencing Mosby? Lee died soon after this, so it is hard to attribute it to him.

I did find the reference in Douglas Southall Freeman’s biography of Lee to that, but that was referenced back to another older book. Here is the link to the older book:

http://www.fullbooks.com/Recollectio…l-Robert7.html

In part 7 of that book I found the following quote, which is the basis for Freeman’s assertation,

Quote:

“Mr. Cassius Lee was my father’s first cousin. They had been children

together, schoolmates in boyhood, and lifelong friends and neighbours.

He was my father’s trusted adviser in all business matters, and in

him he had the greatest confidence. Mr. Cazenove Lee, of Washington,

D. C., his son, has kindly furnished me with some of his recollections

of this visit, which I give in his own words:

“It is greatly to be regretted that an accurate and full account of

this visit was not preserved, for the conversations during those

two or three days were most interesting and would have filled a

volume. It was the review of a lifetime by two old men. It is believed

that General Lee never talked after the war with as little reserve

as on this occasion. Only my father and two of his boys were present.

I can remember his telling my father of meeting Mr. Leary, their old

teacher at the Alexandria Academy, during his late visit to the

South, which recalled many incidents of their school life. They talked

of the war, and he told of the delay of Jackson in getting on

McClellan’s flank, causing the fight at Mechanicsville, which fight

he said was unexpected, but was necessary to prevent McClellan from

entering Richmond, from the front of which most of the troops had been

moved. He thought that if Jackson had been at Gettysburg he would

have gained a victory, ‘for’ said he, ‘Jackson would have held the

heights which Ewell took on the first day.’ He said that Ewell was

a fine officer, but would never take the responsibility of exceeding

his orders, and having been ordered to Gettysburg, he would not go

farther and hold the heights beyond the town. I asked him which of

the Federal generals he considered the greatest, and he answered

most emphatically ‘McClellan by all odds.'”

First, this points out that it is NOT a full account of what transpired & furthermore, it is inaccurate. Ewell did not take the heights at Gettysburg the first day & lose them. Since the two quotes (Mosby’s & Lee’s) are word for word the same, I am going to say that perhaps Cassius remembered the conversation wrong & was drawing from the earlier quote. Or perhaps Lee said that, but he was drawing from the earlier quote. Certainly Robert E. Lee dies less than 4 months after this was supposedly said….perhaps a bit of embellishment on Cassius’s part? This is simply one of those things in history that you will have to decide & judge for yourself.

Quote:

The following conversation of General Robert E. Lee is taken from the biography of Grant by James Grant Wilson.

“Within a few weeks of Grant’s death, a member of General Lee’s staff said to a friend, who had mentioned Hancock’s high opinion of his old chief: “That reminds me of Lee’s opinion of your great Union general, uttered in my presence in reply to a disparaging remark on the part of a person who referred to Grant as a ‘military accident, who had no distinguishing merit, but had achieved success through a combination of fortunate circumstances.’ General Lee looked into the critic’s eye steadily, and said: ‘Sir, your opinion is a very poor compliment to me. We all thought [pg. 26] Richmond, protected as it was by our splendid fortifications and defended by our army of veterans, could not be taken. Yet Grant turned his face to our capital, and never turned it away until we had surrendered. Now, I have carefully searched the military records of both ancient and modern history, and have never found Grant’s superior as a general. I doubt if his superior can be found in all history.'”

I hope this helps in your search!

Excellent attention to detail, Jon! I have always thought that Lee’s quote—if legitimate—perhaps reflected Lee’s self interest (“I did well against Mac, so he has to be their best”) as much as his actual opinion. And your production of the 1867 Mosby quote certainly puts a different focus on things.

In my coming book on James Longsteet, published by Savas Beatie, coming out in May (estimated printing date) I read the Cazenova Lee note books that are at the Lee Fendall House in Alexandria,VA. I can confirm, Cazenova asked his uncle who he thought was the best general on the Union side, and Lee told him he liked McClellan the best. I also cover what his reactions were about Grant and Jackson. You will probably be surprised to know that what Cazenova actually wrote in his notes from the conversation was not positive on Jackson.

Agreed. McClellan faced Lee at his strongest, Grant at his weakest. Lee beat Grant at every battle but Grant eventually wore him down arbite at great cost of men.

The very definition of the Lost Cause. There is a difference between deter and defeat. Grant’s strategy was an overall continental strategy while Lee’s was merely local.

Lee fought on his home territory again and again. Grant never had the 3 to 1 attacker to defender ratio while in the mobile phase of operations. Grant vs McClellan on generalship argument is beyond silly….”Basically that wrestler that pinned me over a 10 month period is no good but the the one that forfeited is gold”, General Lee

Lee knew McClellan would eventually get around to winning the war for the Union.

Ironically, I believe that’s what Grant actually did. No “woulda/coulda/shoulda”, which is always the case with McClellan.

I think Grant recognized McClellan could have the won war too.

Despite Grant’s observation that McClellan should have destroyed Lee at Antietam, I suppose. That’s the neat part of the quote attributed by Young that always seems to get left out. Of course, Grant also said that his most feared opponent was Joe Johnston.

Great article. I think one reason Lee respected McClellan was that he went right at Richmond along the James River. Lee, Grant, and just about every commander saw this as the best line of operations in Virginia. Lincoln and Halleck preferred the overland approach which played right into Lee’s strengths. Grant of course followed that line, but only after Lincoln and Halleck gently overruled his plans to strike along the James or in North Carolina.

In that case. One would also respect Gen. Hooker for reorganizing and improving the Army of the Potomac in the months before the Battle of Gettysburg, in addition to his effective leadership of the army in June of 1863 to counter Lee’s move into Pennsylvania. Has anyone written about how the Battle of Gettysburg may have been fought if Hooker had been in command instead of Meade. It would be particularly interesting to think of how Hooker would have handled Gen. Sickles’ repositioning on the second day. So many ifs…

My comment was in response to that of Henry Fleming.