Kernstown’s Wounded in Winchester

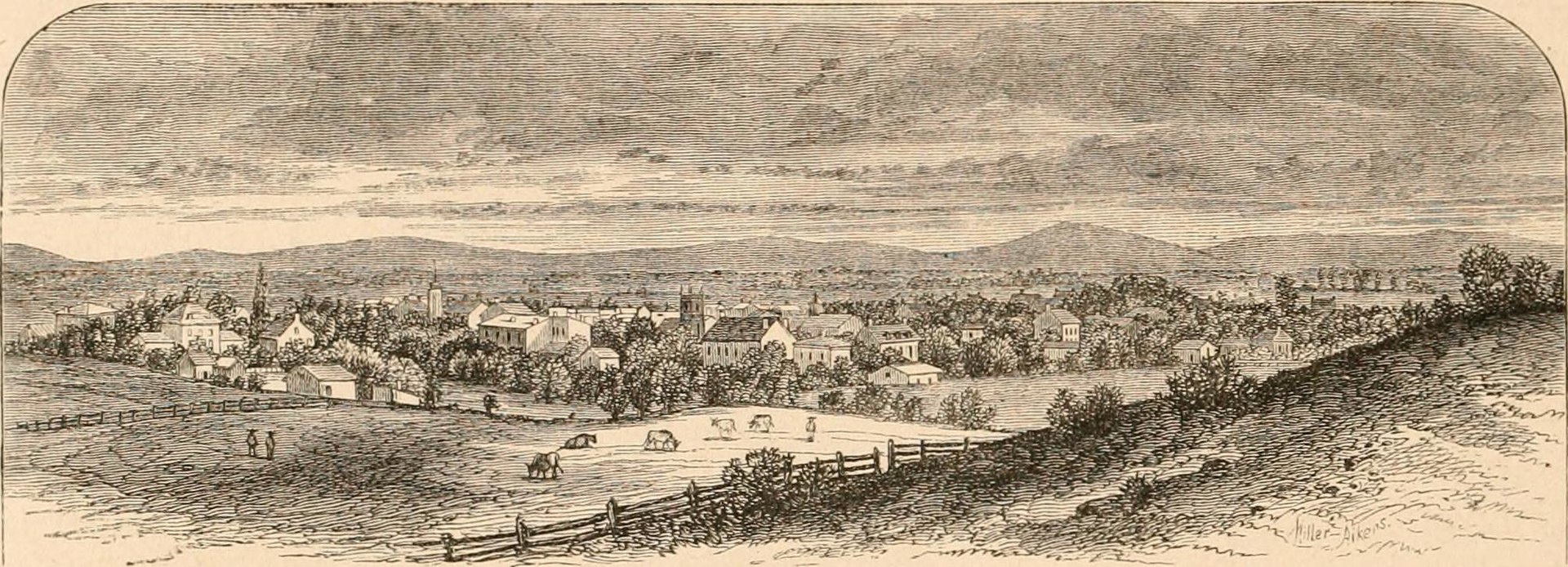

The battle of Kernstown on March 23, 1862 resulted in over 1,000 casualties and a Federal victory in the lower Shenandoah Valley. To be precision, General “Stonewall” Jackson’s early reports on Confederate losses listed 80 killed, 75 wounded, 263 missing (718 total casualties) while Union records showed 118 killed, 450 wounded, and 22 missing or captured (590 total casualties).[i] When the fighting ended, Union troops held the battlefield and they began transporting the wounded to Winchester, about four miles away. Winchester’s history as a military hospital town began its first bloody chapter.

The town had already had an experience with sick soldiers. During the winter of 1861-1862 while Jackson’s Confederates quartered nearby, thousands of troops fell ill. According to Union diarist Julia Chase, there were 1,800 sick men in town, and another civilian, Robert Conrad, believed that 3,000-4,000 sick filled the town and camp as a result of the Romney Expedition.[ii] The illnesses did not confirm themselves to the military camps or hospitals, leading to an outbreak of sicknesses among the civilian population, too. However, the as the largest fight east of the Allegheny Mountains since First Manassas, Kernstown’s fighting resulted in hundreds of wounded troops and pulled volunteer civilians into the hospital scene.[iii]

Wounded likely straggled toward Winchester during the battle itself, but once the Union troops had gained the field, more organized evacuation of the wounded took place. In Winchester, the public buildings were quickly turned into hospitals. The courthouse, hotels, banks, and some churches sheltered the fallen and became the operating rooms for the Union doctors. The Confederate wounded still on the field were eventually taken to Winchester; those unable to make the journey to military prison stayed in the hospitals.

Unionist David Hunter Strother wrote in his March 25 diary entry:

“Last night I visited the courthouse where a number of wounded of both armies lay…. In the vestibule lay thirteen dead bodies of United States soldiers and the courtroom was filled to capacity with wounded, all of a serious nature…. A few stifled groans were heard occasionally, but as a general thing the men were quiet. There was another storeroom opposite Taylor Hotel where we saw a number of wounded, all Federalists. This morning I visited the Union Hotel where I saw two rooms filled with wounded and seven dead.”[iv]

Interestingly, Union authorities prevented civilians — especially Winchester’s Confederate sympathizers — from visiting the battlefield, even to bring medical relief. Cornelia McDonald recalled:

“No one knew who was dead, or who was lying out in that chilly rain, suffering and famishing for the help that was so near, and would have been so willingly given but for that barbarous order that no relief should be sent from the town. No eyes closed during those nights for the thought of the suffering pale faces turned up under the dark sky, or for the dying groans and helpless cries of those they were powerless to relieve.”[v]

Only after all the wounded had been removed and the Union dead removed and buried were civilians allowed to see the battlefield and assist with burying the Confederate dead. McDonald bitterly surmised that many Confederate wounded died for lack of prompt medical attention that might have been given by the civilians.

Cornelia McDonald voluntarily left home and went to see if she could aid the wounded in the hometown. It is worth noting that while she and other eyewitnesses write “Every available place was turned into a hospital” they do not mention Winchester’s private homes turning into hospitals during this battle’s aftermath. However, the courthouse, banks, hotels, and churches were certainly filled with wounded. This allowed a distinction for how the civilians interact with the wounded after Kernstown: voluntarily. No one’s home (as far as I have read) became a hospital this time. The civilians went to the military hospitals, interacted with the surgeons and wounded, and then went home. In later battle and campaign aftermaths, Winchester civilians would open (or be forced) to convert their homes into hospitals.

McDonald first went to the Farmer’s Bank where she found “some ladies standing by several groaning forms that I knew were Federals from their blue garments. The men, the surgeon said, were dying, and the ladies looked pityingly down at them, and tried to help the, though they did wear blue coats, and none of their own were there to weep over or help them.” The scene began to awaken a new emotion in the staunch Confederate civilian.

Continuing her walk through the town, McDonald later wrote:

“I went from there to the court House; the porch was strewed with dead men. Some had papers pinned to their coats telling who they were. All had the capes of great coats turned over to hide their still faces; but their poor hands, so pitiful they looked and so helpless; busy hands they had been, some of them, but their work was over.

“Soon men came and carried them away to make room for others who were dying inside, and would soon be brought and laid in their places. Most of them were Yankees, but after I had seen them I forgot all about what they were here for….”[vi]

Like most of Winchester’s civilians, the aftermath of Kernstown was McDonald’s first experience with mass-casualty situation. It would not have been the first time she had seen death, even soldiers’ corpses. But it was the first time she saw rows and rows of dead, dying, or hurting soldiers. The fierceness of her Southern sympathies softened as she made the realization of common humanity.

Kernstown’s aftermath became the first chapter of many for Winchester’s saga as a hospital town for wounded soldiers. Three major battles on the outskirts of town still lay ahead on the timeline. And hundreds of wounded would pass through the town after Antietam, Gettysburg, and other battles or skirmishes. For the civilians of Winchester — mostly Confederate supporters — the need to care for wounded soldiers created the few united moments. In the face of human suffering and death, they forgot “what they were here for” and volunteered to save lives or ease dying for the soldiers in blue and gray.

Sources:

[i] Gary L. Ecelbarger, “We Are In For It!” The First Battle of Kernstown (Shippensburg, White Mane Publishing, 1997) Pages 273-277.

[ii] Jerry W. Hollsworth, Civil War Winchester (Charleston, History Press, 2011) Page 51.

[iii] Gary L. Ecelbarger, “We Are In For It!” The First Battle of Kernstown (Shippensburg, White Mane Publishing, 1997) Page 212.

[iv] David Hunter Strother, edited by Cecil D. Eby, Jr., A Virginia Yankee in the Civil War: The Diaries of David Hunter Strother (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961). Page 20.

[v] Cornelia P. McDonald, A Woman’s Civil War: A Diary, with Reminiscences of the War, from March 1862 (New York, Random House, 1992, 2003 edition) Page 37.

[vi] Ibid., Pages 37-38.