From Monocacy to Danville: Captured Soldiers of the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry

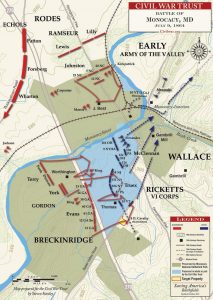

On July 9, 1864, a small United States force under Major General Lewis Wallace faced off against Lieutenant General Jubal Early’s Army of the Valley as it pressed onward towards the national capital, Washington D.C. Early’s troops hoped to pressure or attack the city, while Wallace’s command had been thrown together to buy time. By the time they positioned themselves near Monocacy Junction to the south of Frederick, Maryland, Wallace’s mostly-untested command was reinforced by Brigadier General James Ricketts’ division from the Sixth Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Among those reinforcements were the men of the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry, which had been raised primarily from York and Adams Counties. After a difficult early service involving a crippling defeat at the Second Battle of Winchester in 1863, the regiment had proved itself during the Overland Campaign.

That July morning, Union troops defended river crossings. Confederate troops tried to flank the bridges by crossing a ford and ran directly into Ricketts’ men. Ricketts repulsed the first attacks, but continued pressure, heavy artillery fire, and Confederates overlapping their flanks meant there could only be one outcome. Despite stiff resistance, the significantly larger Confederate force pummeled Wallace’s command into retreat. In the chaos, many men were swept away from the main body of the 87th; a July 13 letter quoted in a newspaper claimed that at that time 126 men were missing.[1] Though most of this number rejoined the regiment, dozens were captured.

Ultimately, the Confederate force was delayed by the action, and it’s generally accepted that the delay allowed Union reinforcements to reach Washington in time for the July 12 battle of Fort Stevens, which dashed Early’s hopes. However, the 87th had suffered during its fight on the southern end of the Union line. The regimental history noted 74 total casualties after the scattered men made their way back. Since the unit had been worn thin by the Overland Campaign and actions at Petersburg, only around 200 men answered the muster call on July 10.[2]

Thirty-one men were alive but captured. Brought with the Confederate army as it continued towards the capital, they sat nervously as they listened to the artillery from Fort Stevens. Early’s retreat must have given them mixed emotions. On the one hand the capital had been saved, due in no small part to their action at Monocacy, but now they were being marched south. Taken to Winchester, they trudged through the Shenandoah Valley while dining on flour paste, passing through Staunton, Charlottesville, and by rail to Lynchburg. In that last city, they were searched for valuables and sent onward to Danville. Sadly, this contingent were not the first soldiers of the 87th to be sent to Danville. A number of soldiers captured near Winchester in 1863 spent some time in Danville before being further dispersed. On June 23, 1864, nearly 100 men were captured during fighting at the Weldon Railroad, and this second group also passed through Danville, while the officers were forwarded to Macon, Georgia. At the end of the war in April 1865, the Sixth Corps with the 87th Pennsylvania included came to Danville, and we can only wonder if they knew how many of their friends had been imprisoned or died there.

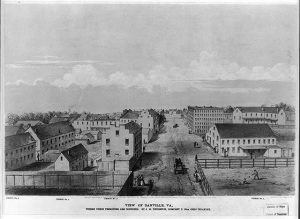

The regimental history, compiled from veteran accounts, recalled Danville’s prison as “a large tobacco warehouse, nearly full of prisoners…The medical attendance was poor and a number died of a fever.”[3] Danville’s prisoner camp was indeed comprised of converted tobacco warehouses, as six had been repurposed into structures that held as many as 7,000 Union soldiers total. Conditions were cramped, and medical treatment and food were minimal. Alfred Roe of the 9th New York Heavy Artillery, also captured at Monocacy, provided a detailed description of the Danville prison and noted the food rations when he arrived: “During the months of August and September we are given corn bread and occasionally a soup made of refuse bits of bacon, sometimes of fresh meat — including lights or lungs. The bacon is rancid, and the vegetables in it are not very inviting, consisting of stray cabbage leaves and a leguminous article known by us as ‘cow pea’… but poor as this soup was there came a time when we would have joyously hailed its advent.”[4] He described the cornbread as made from both corn and its cob, and further described it as rather unappealing, and other prisoners claimed it was unsifted and made with stagnant water from the canal. Eventually, rations dwindled only to the cornbread.

Major Abner Small of the 16th Maine Infantry, who had been captured at Gettysburg and was held in Warehouse Number 3, wrote that “Our quarters were so crowded that none of us had more space to himself than he actually occupied, usually a strip of the bare hard floor, about six feet by two,” noting the men lay in rows with only small aisles between.[5] In fact, illness was so rampant that in early 1864 Danville residents wrote to the Confederate Secretary of War asking for the camp to be moved elsewhere. They feared the diseases would spread, as the prisoners were held in the core of the city. One year later, Confederate Lieutenant Colonel A.S. Cunningham officially inspected the prison and provided the most complete and damning account of conditions:

The prisons at this post are in a very bad condition, dirty, filled with vermin, little or no ventilation, and there is an insufficiency of fireplaces for the proper warmth of the Federal prisoners therein confined. This could be easily remedied by a proper attention on the part of the officers in charge… The prisoners have almost no clothing, no blankets, and a very small supply of fuel. In some of these cases, perhaps, the state of things cannot be remedied by the officers in charge. The mortality at the prison, about five per day, is caused, no doubt, by the insufficiency of food (the ration entire being only a pound and a half of corn bread a day) and for the reasons in addition, as stated above. This state of things is truly horrible, and demands the immediate attention of higher authorities.[6]

In February 1865 relief arrived in the form of clothing and blankets for the prisoners from the United States government. Following that, many of the shattered remnant of the original prison population stumbled out and headed northward for prisoner exchange. The exchange system had been halted in 1863 due to the Confederate government not recognizing captured United States Colored Troops as legitimate prisoners.[7] Despite the resumption of some exchanges, the last of the prisoners were not freed until the Sixth Corps and the 87th Pennsylvania reached Danville on April 23. This was too late for many men.

In total, seven men of the 87th died in Danville (all of whom had been captured at Monocacy), while several other soldiers from the earlier contingents that passed through Danville died in other prison camps. Among the dead at Danville was Peter Reever of Company D, who died on December 17, 1864. He was my fourth-great grandfather’s brother, and he never came home.[8]

[1] Gettysburg Compiler, July 18, 1864. Courtesy Ryan Quint.

[2] George R. Prowell, History of the Eighty-Seventh Regiment, (York: Press of the York Daily, 1903), 188

[3] Ibid, 248.

[4] Alfred S. Roe, “In A Rebel Prison, or, Experiences at Danville, Va.” in Personal Narratives Fourth Series, No. 16 (Providence, 1891), found at https://sites.google.com/site/roesdanville/

[5] Abner Small, The Road to Richmond: The Civil War Memoirs of Maj. Abner R. Small of the 16th Maine Vols.; with His Diary as a Prisoner of War (University of California Press, 1957).

[6] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, serial. I, XLVI, Part 2, 1151 in James I. Robertson, “Houses of Horror: Danville’s Civil War Prisons” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 69, no. 3 (1961): 344.

[7] Myths that U.S. Grant had ended the exchanges are enduring, despite the fact he was only a regional commander when they were halted. For more, see the National Park Service article “Myth: Grant Stopped the Prisoner Exchange.” https://www.nps.gov/ande/learn/historyculture/grant-and-the-prisoner-exchange.htm

[8] Samuel P. Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-1865 Vol. III (B. Singerly, State Printer: Harrisburg, 1870), 46. One genealogy forum (https://www.genealogy.com/forum/surnames/topics/reaver/18) claims Peter was also among those captured at Carter’s Woods north of Winchester in 1863. Due to the extended closure of the National Archives, I have yet to acquire his records to confirm this, as other sources do not mention an 1863 capture.

Even though Grant didn’t stop the prisoner exchanges, I wish that he had reinstated them. It would have saved a lot of suffering and death for the prisoners. I understand the concern about the Colored troops lack of exchange.

I agree that it could have lessened suffering – the system relied heavily on exchange. However, the blame lies squarely on the Confederate government and armies refusing to treat USCTs as legitimate soldiers, instead treating them as escaped slaves (even if they’d never been enslaved).

I need to know more about who attacked the 87th Pennsylvania and it’s brigade

John B. Gordon’s Division, notably Clement Evans’ brigade of Georgians.

I’ve always thought it ironic that this regiment was not at the Battle of Gettysburg – kinda like the Fredericksburg-raised 30th Virginia was only at one of the 4 battles around its hometown, and not engaged in that one.

Absolutely. They barely missed it, mustering out in Harrisburg in mid-May. Had they been there, they would have been in the thick of it near Ziegler’s Grove with the rest of the brigade.

Thank you for this research and post. My g-g-g-grandfather 87th PVI Pvt Martin J Klinedinst was hit with shrapnel in both legs on July 9th, 1864 and taken to Danville. After reading of the prisoners trudging through the Shenandoah Valley, I could only imagine what it would have been like wounded in both legs. He was released in February 1865, but received little recognition of his injuries because he was treated by Confederate medical staff. No US paperwork existed which made it very difficult for him to get his pension. Luckily for us this required multiple affidavits from other 87th PVI members that saw him wounded. These detailed descriptions allowed me to visit the spot where he fell and was taken prisoner.

Mayor Helfrich,

Thank you for reading, and for your civil service to the community our ancestors called home! I’m glad to hear this helped tell Martin Klinedinst’s story, and I’m glad to have found someone who’s relative shared this experience with mine. Those pension records must be such a great family history resource, and it is awe-inspiring that you could locate the spot.