Baseball: The Confederacy’s “National Pastime”

ECW welcomes back guest author Bruce Allardice

Baseball has often been termed America’s “National Pastime.” But the game was the Confederacy’s “National Pastime” as well.

The hoary myth that Confederate soldiers learned the game from their northern counterparts needs to be shelved alongside the myth that Abner Doubleday invented baseball in 1839. In fact, baseball was played in every southern state prior to the Civil War. Baseball clubs had formed in such disparate cities as Norfolk, Virginia; Augusta and Macon, Georgia; Houston and Austin, Texas, and most especially, New Orleans, the south’s largest city. Prior to the war New Orleans boasted more baseball clubs (22) than did northern cities such as Chicago, Milwaukee, Detroit, Pittsburgh or Cincinnati.[1] Various bat-and-ball games, under names such as “round” or “Town” ball, had been played in the south for decades. Antebellum southern newspapers published the latest rules of the game, and often reprinted New York newspaper accounts of ball playing in Gotham. Ads for baseball equipment appeared in numerous antebellum newspapers.[2]

The southern interest in baseball continued into the Civil War. The Protoball website (www.protoball.org) of the Society of American Baseball Research (SABR), which tracks pre-1871 baseball, contains 400 references (mostly brief) to Civil War soldiers playing baseball. About 13% of these reference Confederate play. Confederate soldiers played in the Army of Northern Virginia, the Army of Tennessee, in the Trans-Mississippi armies, in every army, in every year of the war. Confederate POWs even played in every northern prison where space allowed baseball to be played, at (among others) Johnson’s Island, Elmira, Rock Island, Camp Morton, Camp Butler and Fort Warren.

Perhaps the first wartime mention of Rebel baseball comes In November 1861 when the Charleston Mercury reported that Confederate troops were stuck in soggy camps near Centreville, Virginia. Heavy rains created miserably wet conditions so that “even the base ball players find the green sward in front of the camp, too boggy for their accustomed sport.”[3]

As might be expected, Louisiana units, whose rosters contained most of the prewar New Orleans ballplayers, often played baseball in their Virginia camps. The Richmond Examiner, April 2, 1864, mentions “a friendly match of base ball, played between Hayes’ [sic] and Stafford’s Second [Louisiana] Brigade, of the same corps, which match was won by General Hayes’ brigade.” Private W. P. Snackenberg of the “Louisiana Tigers” recalled postwar: “We went back to our camp and stayed there all winter and until late April 1864. Only doing picket duty on the banks of the [Rapidan] River and playing base ball. During the winter, we fought a snow-ball battle with the Brigade of North Carolina and Virginia.”[4]

Soldiers from other states, and other armies, also played. While in camp near Dalton, Georgia, in early 1864, Florida soldiers were joined in the play by their officers: “The boys are killing time in camp by playing ball, which is such good exercise that it will fit them for the fatiguing marches to be taken this summer. The Soldiers here are undoubtedly, at this time more lighthearted and like schoolboys than I ever saw them. Maj. Lash and Col. Badger often play ball with the men.” Reports from units in other states include Toombs’ Georgia Brigade, the 5th Alabama Infantry, and the 2nd Texas Cavalry.[5]

Like their northern counterparts, Confederate clergymen, newspapers, and civil authorities encouraged baseball playing as a healthy exercise. In early 1862 a Charleston newspaper echoed this theme and warned of a baseball equipment shortage: “’Every volunteer who has been in service, has realized the tedium of camp life . . . there is waste time, which might be used advantageously at such manly exercises as cricket, base ball, foot ball, quoit pitching, etc.’’ That paper lamented the shortage of sporting goods available for the men and called for hardware dealers to supply quoits and also cricket and base ball bats. “For want of such things,” it ominously concluded, “the time of the soldier is mainly spent playing cards.’’ Another CSA chaplain wrote: “At leisure hours I frequently engaged with the young men on my regiment in a game of base-ball, for exercise in part, but principally to effect what it was ever my purpose to do, viz., to draw men out from their tents into the light of day, where evil practices are discouraged or corrected.[6]

Often Union soldiers watched the Confederates play ball. Private John G. B. Adams of the 19th Massachusetts recalled that in early 1863, when the regiment was stationed opposite Fredericksburg, Union soldiers watched the Confederates playing ball games across the river. “We would sit on the bank and watch their games, and the distance was so short we could understand every movement and would applaud good plays.”[7]

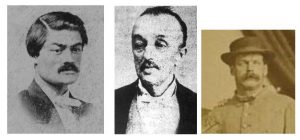

Perhaps the most famous game of rebel baseball was played in 1864. The prior year the bulk of Lee’s first Louisiana Brigade had been captured at Rappahannock Station, and the brigade’s officers (many of them prewar baseball players) were sent to the Johnson’s Island POW camp. They promptly secured bats and balls and formed baseball teams. Lieutenant Michael McNamara of the 7th LA organized one such club, while Lt. Charlie Pierce, also of the 7th, regarded as the best ballplayer in New Orleans, captained the “Southern” nine. Confederate Colonel D. R. Hundley recalled one resulting game with great excitement in his diary on August 27, 1864: “During the progress of the game, nearly all the prisoners looked on with eager interest, and bets were made freely among those who had the necessary cash, and who were given to such practices; and very soon the crowd was pretty nearly equally divided between the partisans of the white shirts [Southerners] and those of the red shirts [Confederates], and a real rebel yell went up from the one side or the other at every success of the chosen colors. The Yankees themselves outside of the prison yard seemed to be not indifferent spectators of the game, but crowded the house tops, and looked on with as much interest almost as did the rebels themselves.” The POWs enjoyed the game so much that the camp commandant banned future games.[8]

Scholars and history buffs have long debated what was the most famous Confederate unit. The debate continues today, but on almost any list would be Mosby’s Rangers, Morgan’s Kentucky Cavalry, Hood’s Texas Brigade, and the sailors on the submarine Hunley. Each had its baseball connection. One of Mosby’s key subordinates was Sgt. Alexander Babcock, a New York native who played for the prominent prewar amateur club, the Atlantics of Brooklyn. When the war commenced he went south, fought for four years with Mosby, and after the war founded a Richmond baseball club. John Hunt Morgan’s second in command, General Basil Duke, was the star pitcher on a prewar St. Louis club. Morgan’s famous telegrapher, George “Lightning” Ellsworth, helped form the prewar Houston baseball club.

Colonel Van Manning, who often led Hood’s Texas Brigade, headed up a postwar Mississippi baseball club. And the officer who commanded the Hunley prior to George Dixon, CSN Lt. John A. Payne, was elected president of the Alabama Baseball Association after the war.

The Confederacy’s baseball enthusiasm exploded after the Civil War. One 1867 Memphis, Tennessee newspaper noted the baseball clubs were forming “in almost every city, town and village” in Tennessee, “all over” Texas, and in “nearly every town” in Arkansas.[9] Historian Harrison Daniel observes that in Richmond, Virginia, alone, “(b)y the fall of 1866, at least fifteen adult and a dozen junior teams had been formed in the city.”[10] Research in Protoball has identified 751 baseball clubs formed in the eleven Confederate states prior to 1871.[11] The nicknames of dozens of these postwar southern clubs honored such Confederate army icons as Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, along with numerous “Rebel,” “Confederate” and “Dixie” clubs, further emphasizing army connections to baseball. Many of the ballplayers on these clubs were, like Sgt. Babcock, Confederate army veterans.

Perhaps the best evidence of the Confederate army’s acceptance of baseball occurred after the war, when a Richmond baseball club made General Robert E. Lee an honorary member.[12] Lee seems to have happily accepted the honor.

Bruce S. Allardice is a professor of history at South Suburban College, near Chicago. He has authored, or co-authored, 6 books, and numerous articles, on the Civil War, including “More Generals in Gray” and “Confederate Colonels.” He is past president of both the Chicago and Northern Illinois Civil War Round Tables.

[1] See www.Protoball.org.

[2] The best (only?) article on this subject is Bruce Allardice, “The Inauguration of This Noble and Manly Game Among Us,” Base Ball (Fall 2012).

[3] Charleston Mercury, Nov. 14, 1861.

[4] Memoirs of W. P. Snakenberg, Private, 14th Louisiana Infantry, in the Amite New Digest, Aug. 29, 1984. Snakenberg was from Louisiana, and had been a member of the Hope Base Ball and LaQuarte Club, which played weekly in Gretna [across the river from New Orleans]. Company K of the 14th was formed around the Hope Club.

[5] Washington Ives letters, noted in J. Sheppard, “’By the Noble Daring of Her Sons’: The Florida Brigade of the Army of Tennessee,” (FSU Dissertation, 2008), 291-292. The Weekly Columbus Enquirer, Feb. 17, 1863; The Greensboro (AL) Beacon, March 28, 1863; J. W. Jones, Christ in the Camp, or Religion in Lee’s Army (Atlanta, 1867), 472; W. W. Heartsill, Fourteen hundred and 91 days in the Confederate Army (1876).

[6] Charleston Mercury, April 3, 1862. Jones, Christ in the Camp, 472.

[7] Cited in George B. Kirsch, Baseball in Blue and Gray: The National Pastime during the Civil War (Princeton, 2003).

[8] Daniel R. Hundley, Prison Echoes of the Great Rebellion (New York, 1874), entry for Aug. 27, 1864. Kirsch, Baseball in Blue and Gray, pp. 46-47.

[9] Memphis Appeal, May 16, 29, 1867.

[10] W. Harrison Daniel and Scott Mayer, Baseball and Richmond: A History of the Professional Game, 1884-2000 (Jefferson, NC, 2015), 3.

[11] From an April 9, 2022 search of Protoball (www.protoball.org).

[12] William A. Christian, Richmond: Her Past and Present (Richmond, 1912), 417.

Great unique post! But has there been any heated discussion on Black Confederate Ballplayers? Did the Emancipation contain a subclause on white managed black baseball teams? ???

Great comment! Brought a smile to my face.

More seriously, there were African American baseball clubs in New York as early as 1858, and several AA clubs in the south postwar. The gloriously named “Six Shooter Jims” of Houston was one such club.

Thanks! It would be fascinating to discover any evidence of interracial play prior to the war!

I was thrilled to read your post about glorious base ball. I have written several for ECW myself, but the delay in starting the season this year (professional baseball) and being ill off and on combined to silence my usual inaugural post. ECW ought to do one of their books about Civil War base ball. I love it! Thanks so much.

As the game of Baseball pre-dates the start of the Civil War, it certainly was America’s “National Pastime”, and no reason to think it was just a game confined just one region of the United States. Harold Seymour in his book, Baseball The Early years has a pretty good discussion of the evolution of baseball, and only gives some credence to the game being slowed some by the Civil War. Growth of the game was certainly not halted.

And while we may shelve the myth that Union General Abner Doubleday invented the game, we can not deny that the Hall of Fame, where the cherished heroes of my youth and my Dad’s youth are enshrined, and where we can re-live our youth, will be forever in Cooperstown New York.

And announcers will still tell us, in the bottom of the 9th inning, in the 7th and deciding game of a Worlds Series, when the bases are loaded and the home team is behind by just one run…That THIS is the way Abner intended the game to be played!

Not so fast… There was a difference between Base Ball and Baseball. And although Abner Doubleday lingers on as “founder of baseball” due to the efforts of former player (pitcher)/ sporting goods manufacturer/ organizer/ promoter Albert Spalding, the real “creator of baseball” was…

But, to start from not quite the beginning, at the commencement of the Civil War there was Base Ball: played in accordance with Massachusetts Rules (which allowed underarm “pitching”); and New York Rules (that pitched overarm.) Exposed to both forms of the game, Union soldiers gravitated towards New York Rules “because it was tougher, and required more skill, and it did not allow the Massachusetts Rules ‘Catch the hit after no more than one bounce and the batsman was out.’” By the end of the Civil War, New York Rules was THE accepted form of the game, North and South.

As to who created Baseball: the first recorded use of the name in America as ONE word, not two, (or Base-ball with a hyphen) was in late 1862 when New York Tribune reporter Adams S. Hill was informed, “Three times round and out is the rule in baseball.” The phrase was used in reference to an incident involving Major General George McClellan, and can be found on Page 2 col.3 of the Chicago Daily Tribune of 20 OCT 1862; and the man who uttered it was President Abraham Lincoln.

I have written an article on how the game was originally named “base ball” (2 words) in common parlance, and when it changed to one word. See “The evolution of baseball as one word or two,” MLBs Our Game Blog, April 21, 2014. Basically, the one word (Baseball) overtook the 2-word “base ball” in the 1890s.

And while I’d love to credit Pres. Lincoln with the first use of “baseball” as one word, it was given the one-word usage in the NY Weekly Day Book, Nov. 13, 1858, and the NY Ledger, Dec. 7, 1861.

Actually, the major difference between the MA game and the NY game prewar was not the pitching method, as neither allowed modern-style overhand pitching. Nor was it the “first bounce out” rule (the rule existed in the NY game until 1865). Instead, the big difference was in the MA game, a runner could be put out by “soaking” him–hitting him with a thrown ball. This led to a lot of injuries, and also to the softening of the baseball to avoid such injuries.

Exactly the point: What came out of the “grinder” of the Civil War, having evolved at campgrounds and POW compounds, North and South, was Baseball.

Continuing on this Baseball thread…..

On this date in 1869, the Cincinnati Red Stockings defeat Amateurs, 24-15, in Baseball’s first professional game,. Team captain Harry Wright had put all of his players under contract, making the club, which will become known as the Reds, the first pro team in sports history.

The Red Stockings took it easy on the Amateurs that day. A week later in a return match the Red Stockings won 50-7.

The Red Stockings are perhaps more accurately described as the first OPENLY professional team. After 1870 the team disbanded (it lost money) and many of the players (including Wright) migrated to the Boston Team, which adopted the nickname “Red Sox” in honor of the connection.

This was a great read, thanks!

There was an historical novel, To Play For a Kingdom, about a squad of Union men from the 14th Brooklyn playing a squad of Confederates during the Overland Campaign. Its been many years, but I remember it as pretty good.