Battle Born: Nevada’s Rapid Rise to Statehood

ECW welcomes back guest author Katy Berman

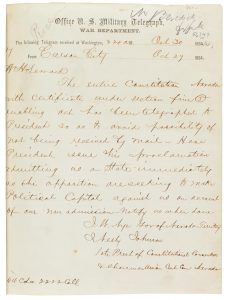

In mid-October, 1864, a telegram containing 16,543 words arrived at the War Department in Washington D.C.[1] It was Nevada’s new state constitution, and President Abraham Lincoln was glad to have it. With it, Nevada could attain statehood and, as the Republican Party dominated Nevada politics, Lincoln would receive three more electoral votes in the November election. Furthermore, passage of the Thirteenth or “Abolition Amendment,” as it was popularly called, became more likely.[2]

Nevada’s Territorial Governor, James Nye, had sent an earlier telegram to Secretary of State William H. Seward, announcing voters’ approval of the constitution. He suggested Nevada be made a state simply on the basis of that information. Seward reported the news at a Cabinet meeting and urged Lincoln to issue a proclamation of Nevada’s statehood. Other cabinet members demurred at the questionable legality of Seward’s suggestion, as did the President.[3]

Undeterred, the ardently Unionist Governor Nye decided to make use of the Overland Telegraph Line that had been completed two years before. Operator James H. Guild sent the telegram first to Salt Lake City, having spent seven hours on his dots and dashes. From Salt Lake, it traveled to Chicago, on to Philadelphia, and finally the capital, a journey of two days. There were 175 transcribed pages, and the cost of the telegram was $4,313.27.[4] On March 3, 1865, Congress appropriated $3,416.77 to Nevada as partial reimbursement.[5]

Lincoln received the telegraphed constitution on October 17; on Oct 31, 1864, eight days before the election, he proclaimed Nevada the newest state in the Union. The country elected him to a second term, perhaps more to General William T. Sherman’s credit than Nevada’s. Still, there was the upcoming and crucial vote in the House of Representatives on the abolition amendment. The President hoped Nevada’s one vote would bolster the two-thirds majority needed to pass the resolution. As Lincoln remarked to Representative James Rollins of Missouri, “The passage of this amendment will clinch the whole subject. It will bring the war, I have no doubt, rapidly to a close.”[6] Would Nevada’s one vote might make a difference?

Nevada’s rapid rise to statehood paralleled its sudden acquisition of territorial status. Without the seceded states to raise objections, Nevada Territory had been carved out of the western portion of the Utah Territory in February, 1861. The region was rich in mineral resources, particularly silver, and prone to lawlessness. Settlers hoped territorial courts would curb the violence, but there was little abatement.[7] By the time of Nevada’s first constitutional convention in September, 1863, the editor of the Gold Hill Times called Nevada “the slaughterhouse of the world.”[8]

There was benefit in remaining a territory: the Federal Government provided subsidies to territorial governments for official salaries and other expenses, while states have to raise all their own revenue[9]. Nevertheless, by 1863, most Nevadans desired statehood. The first (unauthorized) constitutional convention failed, in part, because it ran a partisan slate of candidates for state offices. Additionally, opposing factions could not agree on terms of taxation for mining enterprises. [10]

By September 1864, Nevadans were ready to try again. In March of that year, Congress had passed an Enabling Act permitting Nevada Territory to hold a constitutional convention. The act required that Nevada prohibit slavery within its borders, and earmarked unappropriated public lands for the federal government.[11] Those lands could not be taxed by the state, and, once again, the question of taxing the mines, almost entirely on public lands, nearly sank the convention. It was heatedly debated, amendments and provisions were proposed, language was parsed until a compromise was reached. Delegates felt the weight of responsibility to create a constitution. They knew “that there are two objects for forming this State Government. One is the amendment to the United States Constitution abolishing slavery . . . The other object is that there is a remote possibility that the election of the President of the United States, soon to take place, will not be decided by the people.” It was feared that the election would be thrown to the House where each state, including Nevada, would cast a single vote.[12]

To save time, the act conveniently gave Congress the right to waive its review and approval of Nevada’s constitution. President Lincoln might have proclaimed statehood upon the basis of the telegraphed constitution, but he waited to see the official copies sent by overland mail and around Cape Horn.[13]

Lincoln won by an easy margin of 500,000 votes on election day, 1864; however, the abolition amendment was still in trouble. It had passed the Senate on April 8, 1864, but failed in the House two months later. President Lincoln admonished Congress in his December 6 message, “that almost certainly, the next Congress will pass it if this does not.” The November elections had promised such a result.[14]

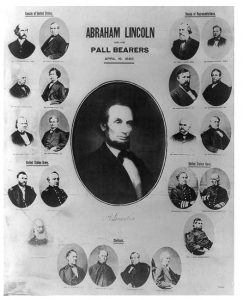

Two weeks later, the amendment narrowly passed, one hundred nineteen to fifty-six. There were only two surplus votes after the two-thirds majority was achieved. Nevada’s first Representative, and close friend to the President, Henry Gaither Worthington, supplied one of them.

Worthington, who served only three months, had one more sad duty to perform in Washington. On April 19, he was one of twelve Congressional pallbearers that bore Lincoln’s casket up the east steps of the Capitol to the Rotunda where it was placed on a hastily constructed catafalque. Worthington had visited the White House on the afternoon of April 14, and declined an invitation to Ford’s Theater. A day later, he sat at the bedside of the dying President. [15]

It was during Nevada’s second constitutional convention that Thomas Fitch, delegate from Storey County, reflected memorably on Nevada’s present and future:

We enter the Union sir, if the people shall decree that we enter it at this time, under circumstances most peculiar. Our young state will be battle-born, but she will live and grow when the civil strife surrounding us shall become a memory[16].

“Battle-Born,” although it appears on the state flag, is only the unofficial state motto of Nevada. The real motto, “All for Our Country” was adopted by the Nevada Legislature in February, 1866. Yet, Guy Rocha, former state archivist, believes legislators had the circumstances of Nevada’s statehood in mind. He suggests, “The motto essentially states that Nevada, first and foremost, would give all its allegiance to the United States.”[17]

“Battle-Born” or “All for Our Country,” both convey Nevada’s unique and timely entrance into the Union.

Katy Berman is a retired elementary-school teacher residing in New Jersey. She earned her Bachelor’s Degree in English at the University of California, Berkeley and her Master’s in American History through American Military University. For several years, she has reviewed books for “The Civil War Courier.”

[1] “National Archives Celebrates the 145th Anniversary of Nevada Statehood,” Sept. 23, accessed April 10, 2022,www.nationalarchives.gov.

[2]Earl S. Pomeroy, “Lincoln, the Thirteenth Amendment, and the Admission of Nevada,” The Pacific Historical Review 12, #2 (Dec. 1943): 366, accessed April 10, 2022, JSTOR.

Official Report of the Debates and Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention of the State of Nevada Assembled at Carson City, July 4th, 1864 to Form a Constitution and State Government, (San Francisco: Thomas Eastman and Co., 1866):486, accessed April 10, 2022, Google Books.

In the 1864 and 1866 elections, Republicans captured all federal, state, and judicial offices. Wayne Thorley, Political History of Nevada, pg. 163.www.leg.state.nv.us. Accessed May 14, 2022.

[3] F. Lauriston Bullard, “Abraham Lincoln and the Statehood of Nevada,” American Bar Association Journal Vol. 26, #4 (April, 1940):317, accessed April 10, 2022, JSTOR.

[4] National Archives Celebrates.

[5] Bullard, “Abraham Lincoln,”317.

[6] Pomeroy, “Lincoln, the Thirteenth Amendment, and the Admission of Nevada,” 362, accessed April 10, 2022, JSTOR.

[7] Michael W. Bowers, The Sagebrush State, 4th Ed: Nevada’s History, Government, and Politics. (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2013),16.

Act of Congress (1864), Enabling The People of Nevada to Form a Constitution and State Government, accessed April 10, 2022, www.leg.state.nv.us/.

[8] Editorial, Gold Hill News, Carson, Nevada Oct. 26, 1863.

[9] Bowers, The Sagebrush State,18.

[10] Ibid.,19.

[11] Act of Congress (1864).

[12] Official Report,486.

[13] Pomeroy, “Lincoln,”366.

[14] Congressional Globe, Message of the President, 38th Congress, 2nd Session, pg.3, accessed April 10, 2022, memory.loc.gov.

[15] “Lincoln’s Pallbearers,” Sacramento Daily Union, Feb. 11, 1898, accessed April 10, 2022, California Digital Newspaper Collection.

[16] Official Report, 44.

[17] Brean, Henry, “When it Comes to Nevada’s State Motto, Confusion is Born,” Las Vegas Review Journal, June 19, 2014.

I thought that the Congress elected in 1864 didn’t sit until late in the following year? Didn’t Lincoln have to get the 13th passed through the lame duck Congress still sitting in early 1865?

It’s correct that the regular session of Congress ran from Dec to inauguration day in March. Then typically the new term of the Senate would meet in executive session for a week or so to advise and consent to appointments. But it wasn’t until 1872 that Congress mandated election of representatives take place in November (Senators of course were the purview of state legislatures). Prior to 1872 practice on when Congressional elections were held varied by state. That’s why in 1861 Maryland had to hold special elections, due to Lincoln calling a special session for 4 July which was in advance of the “normal” election day (not until October).

Katy Berman, Thank-you for this reminder that “the normal business of government” continued, in spite of the Civil War. One factor not covered in your excellent report: the Transcontinental Railroad and its potential impact on Nevada. Up until eruption of the Secession Crisis of 1860, there was a strong possibility for that business-generating rail line to be constructed much further south, through Texas, New Mexico Territory, Arizona Territory… and miss Nevada completely. The Southern decision to “spit the dummy” resulted in loss of this valuable project, with all the tax revenue, town-creation and political king-making that went with it… and these “benefits” devolved upon the new State of Nevada, instead.

https://gov.nv.gov/News/Proclamations/2019/Nevada%E2%80%99s_Role_in_the_Completion_of_the_Transcontinental_Railroad_and_the_Efforts_to_Preserve_its_History_in_the_Silver_State/

Yes, that’s another interesting part of the story!