A Cold Harbor Sketch Says It All

Arthur McClellan, younger brother of the famous general, served on the staff for both John Sedgwick and Horatio Wright. I had previously expressed hope that his unpublished 1864 diary could fill in some of the major gaps in the Sixth Corps’ reporting of the Overland campaign. As part of a larger digitization of George B. McClellan’s papers, the Library of Congress has since digitized Arthur’s journal. A problem still exists, however… much of the handwriting is difficult to transcribe. Nevertheless, a simple sketch in his entry for June 3, 1864, clearly explains the lackluster Sixth Corps involvement in the infamous Union assault at Cold Harbor.

Entries from the Sixth Corps, particularly its leadership, are conspicuously absent from the Overland campaign volumes of The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1891)—cited throughout this article as O.R. The death of John Sedgwick on May 9 shuffled the organization’s structure, promoting Wright into corps command and David Russell to the head of Wright’s old division. Wright could write when he saw fit, later in the war providing a richly detailed description of his corps’ breakthrough attack at Petersburg on April 2, 1865, including in that a copy of the thorough attack instructions he sent each of his subordinates. For whatever reason, however, he failed to even submit a report for the Overland campaign. The O.R. simply contains a day-by-day itinerary of the basic marching routes for the corps to go along with a disappointingly small array of subordinate reports.

To be fair, the Overland campaign marked a new era of continuous active operations. Many Union officers did not submit their reports until months later. Russell, at the helm of the Sixth Corps’ First Division, was mortally wounded in the Shenandoah Valley on September 19, 1864. His adjutant finally submitted a report in late November that briefly stated for June 3: “…another advance was ordered and attempted along the whole line; but little ground was gained, however, and other works were immediately thrown up under sharp and deadly musketry fire.” (O.R. Vol. 36, Pt. 1, 662-663). George Getty commanded the Second Division at the start of the campaign but was wounded at the Wilderness on May 6 and did not rejoin the corps until Petersburg. Thomas Neill temporarily took his place at Cold Harbor. Though absent for the battle, Getty nevertheless included a description in his own report, enthusiastically noting in mid-October that on June 3 a “…vigorous but unsuccessful assault was made on the enemy’s works, the troops, however, gained a foothold close up to the enemy’s lines.” (O.R. Vol. 36, Pt. 1, 680). Neill departed the corps upon Getty’s return and simply did not provide a report. Neither did James Ricketts, for the Third Division, perhaps owing to the severe wound he suffered at Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864.

Furthermore, of the corps’ ten brigades that marched into the Wilderness, only three retained the same commander by the time they reached Petersburg in mid-June (Emory Upton, Frank Wheaton, and Lewis Grant). Upton’s report from May 4 through June 12 takes up nearly seven full pages in the printed publication, but the newly promoted brigadier general devoted just one line to the day in question: “June 3, another assault was ordered, but, being deemed impracticable along our front, was not made.” (O.R. Vol. 36, Pt. 1, 671). Historian Gordon Rhea, the leading modern voice on the Overland campaign, concurred after his own research, summarizing: “Nowhere did the 6th Corps reach the main Confederate line. Along most of the corps’s front, no advance of consequence was even attempted. The Confederates were simply too well fortified, and Wright and his field commanders knew it.” (Gordon C. Rhea, Cold Harbor: Grant and Lee, May 26-June 3, 1864 [Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2002], 348).

An additional interpretation I would offer for the Sixth Corps’ puzzling inactivity is that we as historians enjoy the benefit of hindsight in knowing that June 3, 1864 is a notable day of the Civil War. At the time, however, the Overland campaign had nearly lasted a full month. There had been days filled with horrific carnage and others where the lines slowly shifted around, probing for a week spot. By the time the soldiers and their commanders got to know the landscape around them, they were again on the march, racing for the next crucial bridge or intersection. Popular depictions of Cold Harbor, with the bells of Richmond tolling in the distance and the Confederates backed up against the Chickahominy and one strong push will end the war seem largely fanciful. Wright may have had orders on June 3 to attack, and though it is no excuse, that did not make the instructions for that day unique in any regard to those before and after it during the campaign.

The portions of Arthur McClellan’s diary for June 3—that I can read—meanwhile suggest that the captain was confident the corps did all it could that day. “We were more successful than the others,” one line reads. McClellan justified the inability to carry the Confederate lines in their front, or even seriously attempt to do so, with the corps’ advance position, gained by successful assault two days prior. “We were so situated that we were exposed to an enfilade fire from both flanks in many parts of our line & lost heavily without being able to inflict any damage on the enemy and we could not advance because the movements on our R.&L. [right and left] were not up with us.” (George Brinton McClellan Papers: Diaries, -1864; McClellan, Arthur; 1864, Jan. 1-Oct. 19, 1864, Manuscript/Mixed Material, Library of Congress).

The Sixth Corps high command did not view their advanced position as a spearhead for the entire assault, instead waiting for the Second Corps to the south and the Army of the James’s Eighteenth Corps to the north to advance first. As Confederate fire and counterattacks subdued those disjointed charges around them, Wright’s men utilized their own personal agency in the manner and hit the ground. Their commanders had great reluctance to prod them any further.

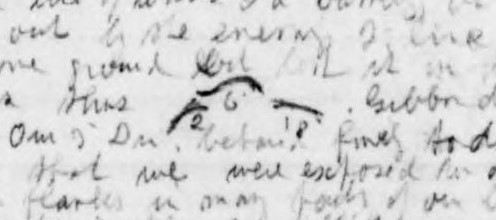

A crude sketch of the Union lines McClellan included in his diary illustrated the conviction among the Sixth Corps that they were already well ahead of everyone else. It lends a bit more earnestness to the most informative communication Wright provided at Cold Harbor—a 7:45 a.m. dispatch to Meade’s headquarters:

“I am in advance of everything else. If I advance my right farther, without a corresponding advance by the Eighteenth Corps, I am, from the form of the enemy’s lines, taken in flank and reverse. My left cannot well be advanced for the same reason; but I have pushed forward my center, supporting it by the divisions on the right and left; the extreme flanks of those divisions to wait for a movement of the corps on their right and left. I think I can carry the enemy’s main line opposite my center, and have ordered the attack, but, as before stated, my flanks cannot move without a corresponding movement of the corps on my right and left. My losses will show that there has been no hanging back on the part of the Sixth Corps, which has so far moved very satisfactorily. I may be pardoned for suggesting that the important attack for our success is by the Eighteenth Corps. This is undoubted, unless I misapprehend the enemy’s position.” (O.R. Vol. 36, Pt. 3, 544).

Wright’s incorrect assumption was in his own role that day, believing his corps was to simply provide support for the movements of the corps on either side. George Meade bore some of the responsibility to clarify, but the mingling of the Army of the Potomac with the Army of the James meant that Ulysses S. Grant ultimately should have taken a greater coordinating role once he determined to launch a frontal assault. Tragically, the Sixth Corps’ malaise meant that Winfield Hancock and William Smith’s men would suffer even greater casualties, with the Confederates in Wright’s front able to shift their fire into the flanks of those Union lines that did charge forward. Rhea estimates that the Sixth Corps suffered 600 casualties, compared to about 1,500 in the Eighteenth Corps and up to 2,500 in the Second Corps. Given the brutal repulse of Smith and Hancock, however, perhaps Wright’s men were simply fortunate to have been pushed no further that day.

Sounds like wishful thinking on Wright’s part. By the end of May the “It’s not my job” viewpoint seems rampant among most of the senior leadership of the AOP. Somehow Lee’s army retained a flexability that had drained out of the AOP. I like Rhea’s analysis; he denied Grant the “butcher” label, by lays into him for hasty tactical offensives undertaken with little reconnaissance. Some Grant fans have seen this “continuous contact” as an example of the tactical reflection of Grant’s strategic vision. Personally, I feel it so blunted the AOP as to allow Lee to detach Early, and delayed Union victory until 1865.

It wouldn’t have mattered what the 6th did. Cold Harbor was a huge tactical error on Grant’s part. Perhaps their ‘lackluster’ response was recognition of that and saved an even greater loss of life.

In the photo of Wright and his staff, note the smiling Charles A. Whittier in his straw hat to the left of Wright. He looks like he is ready for a stroll down Broadway. He was John Sedgwick’s favorite aide and probably the most intelligent staff officer in the army after Ted Lyman.