A Morning Surprise for “Stonewall” and His Staff Officers on June 8, 1862

Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson is famed in the history books for his surprise flank attack at Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863. Lost in the storytelling about Stonewall’s surprise at Chancellorsville and his Shenandoah Valley Campaign “brilliance” in 1862 is the account of when Jackson himself was ambushed and nearly captured. The surprise for Jackson took place in the early morning hours of June 8, 1862…even before some of his staff officers got out of bed or had coffee.

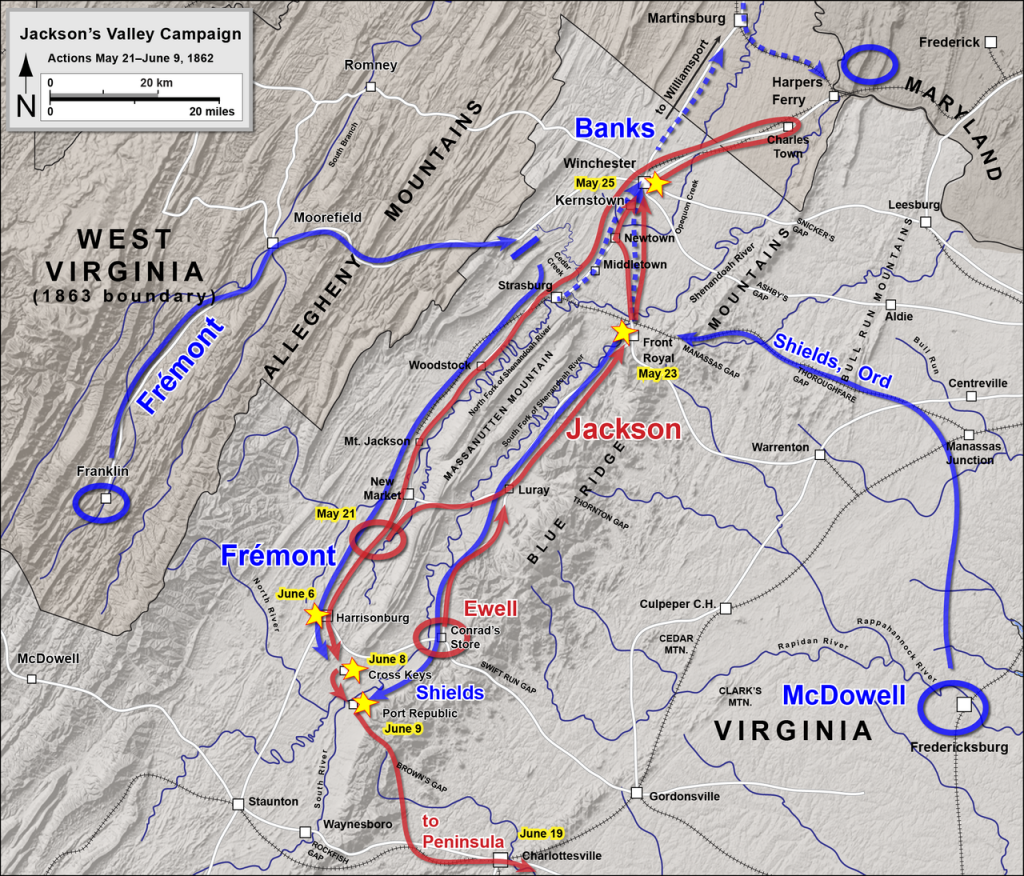

After Jackson’s return to Winchester in the lower Shenandoah Valley (northern part of the Valley) on May 25, 1862, he had little time to rest or allow his troops to recover from their fatiguing marches. While Union General Banks continued his retreat, his compatriots Generals Fremont and Shields returned to the Valley, trying to trap Stonewall. Jackson made a swift retreat, moving south toward Harrisonburg, then pulling east into the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains with their gaps toward Central Virginia.

By Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com, (Wikimedia)

By the morning of June 8, the Union forces closed on Jackson’s position. A detachment from General Shield’s force swung first, trying to gain the bridge at Port Republic and cut off the Confederate retreat, forcing them to fight Fremont and not retreat toward the mountains.

Confederate cavalry in the Valley Campaign had been gallant, but not always useful; Turner Ashby who commanded the horsemen on paper and in theory left much to be desired in military discipline, but his leadership had been lost. Ashby died of wounds not far from Harrisonburg on June 6, leaving Jackson and the soldiers to mourn the loss of one of the rising heroes in the Valley’s Confederate pantheon. A failed Confederate cavalry scout did not provide information about Shield’s advance toward the all-important bridge. Not realizing the approaching dangers, Jackson spent a peaceful night at a civilian home “beyond and south of Port Republic and separated from his troops by that little town and the Middle Branch.”[i]

According to staff officer Henry K. Douglas’s dramatic recounting of June 8’s morning:

Between seven and eight o’clock, while the General and a few of his staff were walking in front of the house, enjoying the morning away from the hum of the camp and watching the horses grazing over the green lot, a courier rode up with a report that the enemy, cavalry, artillery, and infantry, were at the Lewis House, three miles distant…. A lieutenant of cavalry arrived and said the enemy were in sight of Port Republic. And just then a quick discharge of cannon indicated that the little town was being shelled.”[ii]

The peaceful Sunday morning transformed into a battle day, and Jackson needed to reunite with his army for the coming fight. Stonewall got a horse and followed by Captain “Sandie” Pendleton galloped toward the bridge. Henry Douglas chased after them after finding a horse, claiming, “Few of the staff got off in time. If any other crossed the bridge…with the General but Pendleton, I do not remember him. I was the last to get over, and I passed in front of Colonel S. Sprigg Carroll’s cavalry as they rode up out of the water and made my rush for the bridge. I could see their faces plainly and they greeted me with sundry pistol shots.”[iii]

Jackson raced to a hill “overlooking the bridge.”[iv] Looking back toward the river, the general noticed a group of horsemen at the bridge and “called to them loudly and sharply not to stop there, but to come over immediately, waving to them at the same time.”[v] Horrified, Douglas informed Stonewall that those horsemen were not his staff couriers, but were actually Yankees. “To our mutual surprise they wheeled and rode off As they do so, a piece of artillery came up at a gallop, was unlimbered quickly and trained upon us on our side of the bridge.”[vi] To meet the Union artillery threat, a cannon from Poague’s battery arrived near Jackson on the hill.

Still confused, Jackson started shouting commands to the Union cannon by the bridge. While Douglas vainly tried to correct the general, the Union cannon fired and convinced Jackson more effectively. Fully awakened to his danger, Jackson sent Douglas galloping toward the Confederate camp with orders to bring back the first infantry regiment he could find. The 37th Virginia was already on the road, and their charge combined with Poague’s gun, drove back the Union troopers at the bridge and retook the town.

It wasn’t just the village and Jackson’s breakfast in danger. The Confederate supply wagons were under threat. However, a company of the 2nd Virginia Infantry ably guarded the supplies and also helped to drive away Carroll’s cavalrymen. The threat near Port Republic passed for the moment, and the actual battle of June 8, 1862, happened near Cross Keyes. Fremont heard the shots at Port Republic and attacked Ewell’s Confederates to the Yankee general’s demise. Fremont retreated, leaving Jackson to reposition his army and let Shields to try a battle at Port Republic on the following day.

In the midst of the battle drama at Cross Keys, Jackson’s staff was scattered, some rattled by the experience and others actually captured. The chief of artillery, Colonel Stapleton Crutchfield, who had a reputation for liking to sleep in, got captured, but escaped during the skirmish at the bridge. Dr. Hunter McGuire barely escaped capture and went on to have a bad time wrangling ambulances at Port Republic and getting scolded by Jackson for swearing. Lieutenant Edward Willis had a more adventurous time as a prisoner.

Willis “was taken five miles to the rear and placed under guard in a house. There he met a sympathizing young lady, whose anti-Union sentiments he soon discovered. He had not been well, and it occurred to him that he might just as well be worse—an idea which the young lady heartily encouraged. She reported his condition and administered potions to him, awful gruels and bitter tea, but he steadily became worse. To all appearances alarmed, she kept surgeons away from him and almost made him ill in reality by the concoctions she invented and made him taste, to her amusement if not his. The next day…the [Union] retreat was too rapid to include him and he was left behind. His strength returned marvelously and we soon met him returning to us on a captured hose, with its owner sitting quietly behind him.”[vii]

Strategically, Carroll’s raid on Port Republic failed to produce real results though he unknowingly and temporarily discombobulated Jackson and his staff. If the Union cavalrymen had burned the bridge, the could have separated Jackson and the Confederate army from their ordinance wagons…and cut off their Plan B retreat route to Brown’s Gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains.[viii]

The battle of Cross Keys joined the list of Confederate victories in Jackson’s Valley Campaign. It was better to keep quiet the part of Jackson “inviting” Yankees to join his staff’s escape position and directing their artillery. Surprise and mystery are usually identified as hallmarks of Jackson’s military successes, but on the morning of June 8, Carroll’s troopers unknowingly nearly captured Stonewall and successfully impaired his staff’s effectiveness that day.

Sources:

Peter Cozzen, Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008). See Chapters 26 and 27 for Cross Keys and the morning surprise at Port Republic.

[i] Douglas, Henry K. I Rode With Stonewall: The War Experience of the Youngest Member of Jackson’s Staff. (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1968.) Page 84.

[ii] Ibid., 85.

[iii] Ibid., 85.

[iv] Ibid., 85.

[v] Ibid., 85.

[vi] Ibid., 85.

[vii] Ibid., 87.

[viii] Peter Cozzen, Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008). Page 449

I don’t see many references to the Cross Key scrap. About 20 years ago I remember reading a short book by a fellow who bought a farm and learned it was the site of the battle. I recall he was moved by the hallowed ground he had acquired. Too bad I can’t find it now to skim it again!

It’s “Farming a Civil War Battleground” by Peter Svenson. I read it back in 1996. Available today on Amazon (wherelse).

I didn’t know my great-grandfather liked to swear! Don’t blame him.

Scott house was where he was. William Scott, Michael Scott, Ruben Scott and Charles Scott lived there and all were members of Confederate units. Jackson left a copy of his book and ate a peach on porch before leaving in hurry.