The Battle of Memphis and the Fog of War

The battle of Memphis took place on the Mississippi River on June 6, 1862. (You can read posts about it here and here.) Even on the water, the fog of war sometimes hangs heavy over a battlefield. By June 11, confusion about the battle of Memphis was already so rampant that Col. Charles Ellert, Jr., commander of the USS Queen of the West, felt obligated to address the confusion in his official report.

Ellet commanded the Federal ram fleet, which engaged in most of the fighting. As architect of the fleet and the man who struck the first blow in the battle, Ellet was the man primarily responsible for the stunning (and overwhelming) Federal victory. A Confederate bullet hit him in the left knee shortly after his own ship was damaged, leaving him incapacitate with a wound that was deemed serious but not dangerous.

After the battle, Ellet had dashed off a pair of reports on the afternoon of June 6, which he followed with two on June 8. He started with a brief outline of what happened and then offered other key details in the follow-up correspondence. By his second note on June 8, he wrote, “There are several facts touching the naval engagement of the 6th at this place [Memphis] which I wish to place on record.”[1] Already he was feeling the need to correct and clarify.

On June 11, Ellet wrote again. By this point, his knee injury was proving to be more serious than originally believed. And not only was he not recovering, he was showing signs of exhaustion, and at some point in this time he came down with measles, which he caught while in the hospital ward. Despite his deteriorating condition, he attempted to finally report, in depth, “the details of the naval engagement of the 6th instant off Memphis. . . .” In his report, he tried to cut through the chatter and competing stories already circulating:

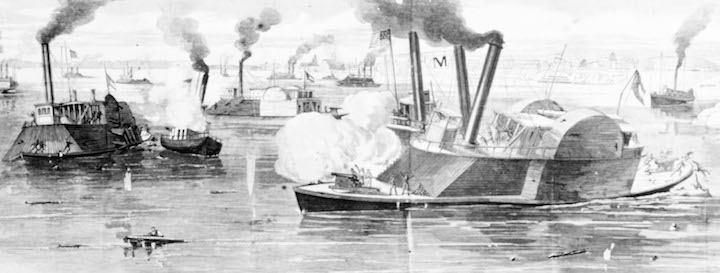

Many versions, differing from each other entirely, have been given by eye-witnesses of these occurrences, who stood in plain view on the levee at Memphis, in our own gunboats, and on the Arkansas shore. These discrepancies are attributable to the fact that there were three rebel rams and two of our own mingled together and crashing against each other and that other rebel steamers were coming up and close at hand. In this confusion the different boats were mistaken for others, and the steamer struck by the Queen disappeared from view beneath the surface of the river. This uncertainty of view was doubtless increased by the accumulation of smoke from the chimneys of so many boats and the fire from our own gunboats.[2]

Ellet’s report continued for another paragraph, the abruptly ended. A footnote in the O.R. explains “Report discontinued at this point, ‘on account of Colonel Ellet’s exhaustion,’ and never resumed.”[3] Ellet died ten days later and so never had the chance to complete his report or shed additional clarifying light on what happened on the river on June 6.

His June 11 report, however, offers a clear and succinct explanation of the fog of war in action and why it’s so easy for events on any battlefield to become so jumbled, confused, and confusing.

————

[1] O. R Vol. X, 909.

[2] O.R. Vol. X, 928.

[3] Ibid, 929.

Thanks for introducing this neglected topic: Memphis… where the mechanical torpedo was developed for use in defending Fort Columbus and Fort Henry. And which city became Capital of Confederate Tennessee upon evacuation of Nashville in February 1862. The Memphis & Charleston Railroad, Backbone of the Confederacy, connected the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River from 1857. And Van Dorn’s Army crossed the river from Arkansas to Memphis in April 1862 pursuant to joining Beauregard at Corinth. The citizens of Memphis, aware that Federal gunboats had been defeated days earlier at Plum Point Bend, lined the riverfront on 6 June 1862 to watch Flag- Officer Davis get whooped again… only to become residents of a Federal-occupied city that same day.

There is a lot of fog to penetrate at Memphis.

Today, 160 years ago, produced an unexpected bonanza for the Union. In Memphis, Dr. A. L. Saunders, the chief developer of Rebel torpedoes in the West, was arrested while attempting to join the Union Army as a Surgeon. He was subsequently sent to Cairo, Illinois “for examination.” See Page 1 Column 5 (two brief articles) in Chicago Daily Tribune https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84031490/1862-06-25/ed-1/seq-1/

In late May 1862, learning of the approach of Davis’s gunboat flotilla from the north, Confederate officials removed the nearly-complete CSS Arkansas from her building site at the old Memphis Navy Yard and moved her down the Mississippi River to a tributary just north of Vicksburg. CSS Arkansas would be completed at Yazoo City (assisted by floating workshop, CSS Capitol) and make history in July 1862. [Attached is 1850s sketch of Memphis Navy Yard https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh-series/NH-02000/NH-2134.html

On 17 May 1862, in response to urgent request for assistance from Colonel Slack, 47th Indiana, commanding Occupation Forces Memphis, Major General Lew Wallace and most of his Third Division arrived in Memphis. However, both Slack and Wallace found themselves without sufficient cavalry, necessary for conduct of screens and patrols. Fortuitously, the 6th Illinois Cavalry commanded by Colonel Benjamin Grierson, arrived at Memphis (from Cairo) shortly after Wallace; and on about 22 May Grierson’s Cavalry was tasked with patrolling south of Memphis. Grierson and his cavalry returned to Memphis 23/24 May and reported to the new senior officer at Memphis, Major General U. S. Grant.

Of course, the above actions of Slack, Wallace and Grierson all took place during the month of JUNE 1862…