Southerners Have Fun with McClellan’s “Change of Base”

At the end of the day, June 27, 1862, George McClellan knew he had been whipped. Fitz John Porter’s V Corps had been fiercely attacked. Its center had broken and Porter’s troops retreated, leaving behind twenty-two guns.1

At the end of the day, June 27, 1862, George McClellan knew he had been whipped. Fitz John Porter’s V Corps had been fiercely attacked. Its center had broken and Porter’s troops retreated, leaving behind twenty-two guns.1

Porter was north of the Chickahominy; the rest of the army lay encamped to its south.2 Mac, in something of a panic, decided to retreat. “We have met a severe repulse to day having been attacked by vastly superior numbers,” he telegraphed that night, “and I am obliged to fall back between the Chickahominy and the James River.”3

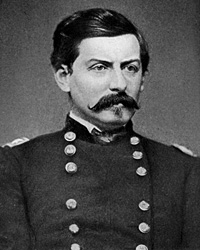

Note that the Young Napoleon did not use the r-word—retreat. Indeed, when he called his generals to headquarters around 11 p.m., he pretended that he had not made his decision (though he had already asked Flag officer Louis Goldsborough for help from his gunboats on the James). As early as 1 p.m. on the 27th, though—ten hours earlier, and well before Lee launched his first assault at Gaines’ Mill—McClellan had warned Secretary Stanton that he might be “forced to concentrate between the Chickahominy & James.” (Ethan Rafuse goes so far as to state that McClellan had begun to ponder “the possibility of changing his base to the James” as early as May 3, when he took Yorktown.) McClellan adopted a happy euphemism for his retreat: “change of base.”

Yet the facts were obvious: after just one battle, McClellan was abandoning his campaign against Richmond, and was ceding the initiative to Lee and the Rebels. Lincoln fell for the sham. “Save your Army at all hazards,” he wired Mac.4

Historians have fallen for it, too. “McClellan, retiring from the Chickahominy, changed his base from White House on the Pamunkey to Harrison’s Landing on the James” (Randall, 1937).5 Allan Nevins actually hails Mac’s move as “the only way to foil Lee,” shifting his base to the James and naval protection for his army, “now in real peril.” “His retreat across country was a masterly operation, executed despite heat, thirst, hunger, and fatigue.”6 (Bataan Death March, anybody?) More recently, Brian Burton argues, with admitted logic, that after Gaines’ Mill, McClellan could have ordered an actual retreat—meaning, retracing back along his route of advance. Instead, the move to the James was lateral, an actual “change of base.”7

Others, though, are not to be taken in. “The ‘change of base’ phrase demonstrates the truism that if anything is repeated enough it becomes accepted as a reality regardless of the facts,” sniffs Clifford Dowdey.8

Confederates, for their part, knew a retreat when they saw one. In his diary entry for June 28, Edmund Ruffin lamented that McClellan “had gained 12 hours of advance in his retreat toward James River.” “McClellan is doggedly retiring toward the James River,” was the diary entry of John Beauchamp Jones for June 29. In his Southern History of the War, Edward Pollard chimes in: “In a short while it became known to our generals that McClellan… was retreating toward James river.” 9

The cowardly masquerade was so comical that one Rebel poetaster found inspiration for a few lines:

Henceforth when a scoundrel is kicked out of doors,

He need not resent the disgrace,

But cry: “My dear sir, I’m eternally yours,

For your kindness in changing my base.”1

————

Notes

1 Stephen W. Sears, To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1992), 249.

2 Vincent J. Esposito, ed., The West Point Atlas of American Wars, 2 vols. (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959), vol. 1, map 46.

3 Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1988), 212-13.

4 Sears, To the Gates of Richmond, 250-51; Ethan S. Rafuse, McClellan’s War: The Failure of Moderation in the Struggle for the Union (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005), 223; Stephen W. Sears, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence 1860-1865 (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1989), 319.

5 James G. Randall, The Civil War and Reconstruction (Boston: D. C. Heath, 1937), 299.

6 Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution 1862-1863 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1960), 134.

7 Brian K. Burton, Extraordinary Circumstances: The Seven Days Battles (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 80.

8 Clifford Dowdey, The Seven Days: The Emergence of Lee (Boston: Little, Brown, 1964), 254.

9 William Kauffman Scarborough, ed., The Diary of Edmund Ruffin, 3 vols. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972-89), vol. 2, 358-59; James I. Robertson, Jr, ed., A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary At the Confederate States Capital, 2 vols. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2015), vol. 1, 123; Edward A. Pollard, Southern History of the War (New York: Fairfax Press, 1977 [1866], 416.

10 “M’CLELLAN’S STRATEGIC MOVE,” Atlanta Daily Intelligencer, July 23, 1862.

Actually, McClellan considered a change of base well prior to June 27, but he failed to implement the change. He received information on May 20 from a reconnaissance pushing to within two miles of the James River that revealed the lack of a Confederate presence in the area, leading him to look into changing his base.

A supply depot on the James was more desirable than his depot at White House Landing on the navigable but narrow Pamunkey River. Attaining a connection to the James would better suit McClellan’s Peninsula operations, as it could provide his forces with the additional protection of Union gunboats and provide better accessibility for his transports.

However, by June 27, McClellan’s actions are better described by the word ‘retreat’ than his term ‘change of base’.

“Change of Base” — aka “Getting the hell out of Dodge” or “Bagging ass” (Philly lingo) … it’s a shame the writers of the day didn’t create memes … Mac would have inspired some great ones.

Steve: It’s not often that one can see a momentary slip up in 19th century transcripts but during McClellan’s testimony before the JCCW on March 2, 1863 he answered one question by starting with “As soon as the retreat – the movement to the James river – was determined upon …” It’s at p 435 of the JCCW Report, Part 1.

Just because someone starts to prepare a contingency, doesn’t mean they have decided on it. Indeed, McClellan prepared for a contingency movement of his base to the James about two weeks before the Seven Days.

Better to have a back-up plan and not need it than need a back-up plan and not have one.

The existing supply base was obviously untenable by the morning of the 27th, and it is simple good prudence to arrange for supplies to come from elsewhere.

McClellan offered two alternatives to the corps commanders on the evening of the 27th. Firstly, they could transfer the entire army to the left bank of the Chickahominy and fight for WHL. Secondly, they could move their position to south of the White Oak, their right on the White Oak and their left on the James (i.e. the position of the 30th), and supply by Haxall’s and Carter’s Landings. Two Corps commanders recorded the events, with McClellan preferring option (1), but all the Corps commanders present, and Barnard, favouring (2). In Heintzelman’s diary, he takes pride in talking McClellan out of option (1).

The intended movement was lateral, with an intention to supply by Carter’s and Haxall’s, and advance via the Bermuda Hundred. As to how they ended up at Harrison’s Landing, which was not McClellan’s intent, that’s an interesting story in which Baldy Smith’s mental breakdown takes centre stage…