The Contextualized Statue of Raphael Semmes

Until June 2020, Raphael Semmes stood on a traffic median along Government Street in Mobile, Alabama—at least his bronze statue did. On the far side of the intersection, the Bankhead Tunnel plunges below the city street and beneath the empty concrete pad where Semmes once stood, then onward, underground, beneath the Mobile River. When Semmes stood here, he had his back toward the water, but a riverside hotel now blocks the view. That water had once made Semmes an international terror.

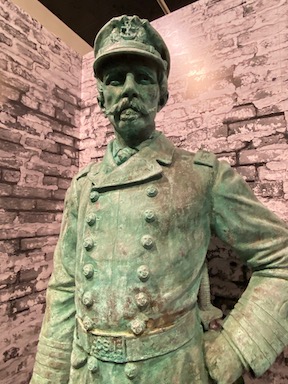

Semmes now enjoys a cooler spot out of the Alabama sun. He has been nestled in a nook in the air-conditioned History Museum of Mobile where visitors can now see him up close.

Semmes’ statue once stood on a twelve-foot pedestal, lifting him above the daily throng. Cars passed along either side of the divided street, and motorists caught at the stoplight in any direction might have been able to spare a glance—if they weren’t quickly checking their text messages or chatting with their passengers. Mardi Gras parades marched right past the statue, sometimes adorning it with tossed beads.

The statue’s new placement in the museum sets Semmes on the floor. At eight-feet, six-inches tall, the statue is still larger than life size—part of the perception of Semmes himself as larger than life—but standing as close to eye level as possible creates a much different interaction for a visitor. It’s easier to examine the statue and contemplate both man and sculpture. People can actually look at it rather than glimpse it as they parade or drive by.

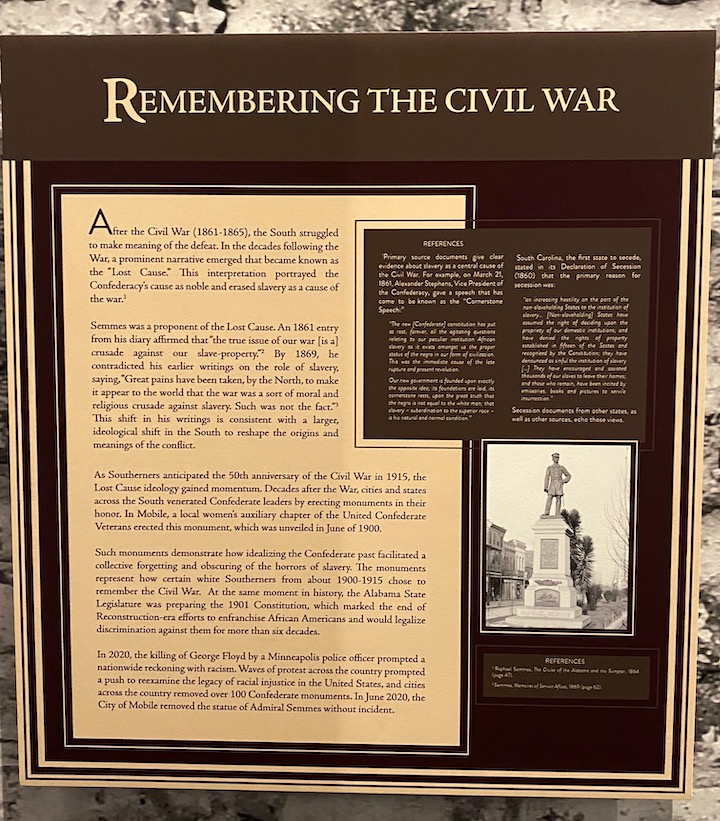

The museum has aided this process with panels that explain who Semmes was and how his statue came to be. Dedicated on June 27, 1900, the statue stood in a public space for 120 years until relocated into the museum. During the protests of the summer of 2020, the statue and its base were vandalized, prompting city leaders to remove the statue. A committee of local stakeholders was formed to discuss the statue’s future. Upon the committee’s recommendation, a space was created for the statue in the history museum.

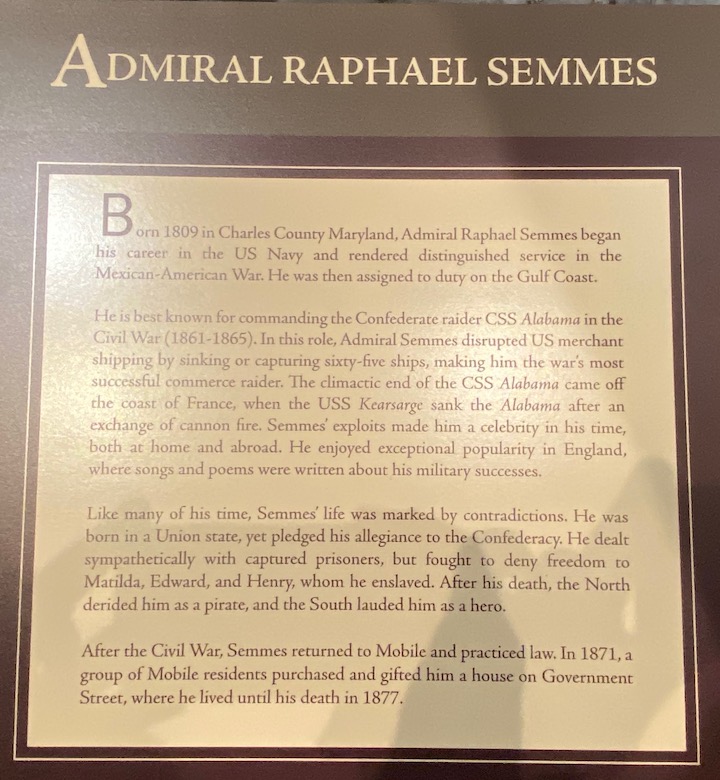

Although one of Mobile’s most famous residents, Semmes was a transplant rather than a native. Born in Maryland in 1809, he moved to the city on the bay after the Mexican-American War. He practiced law and retained his U.S. naval commission until the outbreak of the Civil War, at which time he resigned from the Federal navy to join its newly created Confederate counterpart. Semmes rose to international fame during the war as captain of the commerce raider the CSS Alabama.

Built in Liverpool, England, in 1862, the Alabama captured 65 other vessels over its two-year career, including military and commercial targets. It was finally destroyed off the coast of France in June 1864 by the USS Kearsage. It took Semmes and his crew most of the rest of the year to return to the Confederacy, where they made their way to Richmond and were, of all things, converted into infantrymen. Semmes himself was appointed a brigadier general for the last months of the war.

As one of Mobile’s most famous wartime participants, it’s a little wonder that his admirers chose to erect the statue as a way to commemorate the war’s fiftieth anniversary.

But the same controversy that made Semmes a darling of the Confederacy made him a problematic figure in his own time and continues to make him a problematic figure today. This goes beyond the racial issues that have recontextualized Confederate monuments in our own time. The Confederacy was a government built on the notion white supremacy, and Semmes was an important figure in support of that government. Semmes himself recognized slavery as “the true issue of our war….”

Beyond that, to properly consider Semmes, one must consider: was he a lawfully acting officer of a belligerent nation or was he essentially the captain of a pirate ship?

Commerce raiders are a fact of war. However, international law did not recognize the Confederacy as a legal entity. Thus, the Alabama’s commerce raiding was not an official war act; it qualified as piracy.

So, was Semmes in fact a criminal?

There was, as Kris White explained to me, an effort to file some paperwork to try and lend the Alabama‘s status some legitimacy, although I’ve not had time to dig into yet. I do know, though, that controversy over the Alabama and restitution for the losses it inflicted stretched on for more than a decade after the war. Feelings remained bitter long after.

The general public has little attention span for such technicalities, though, so it’s little wonder residents of Mobile simply saw their adopted son as a Confederate war hero. He led a postwar life as a respected member of the community and worked as a professor at Louisiana State Seminary (the eventual LSU) and as a newspaperman. He died from food poisoning contracted by eating shrimp—as “Gulf Coast” a way to go as I can imagine.

I considered all these things as I admired the Semmes statue in the museum, just as I admired the museum’s efforts to offer a fuller context for the statue.

I know many people advocate leaving statues where they stand in public spaces. If that’s what a public process decides, then so be it. Mobile’s public process chose to offer visitors a different kind of opportunity to interact with their Confederate statue. As a result, I had a much fuller experience with the Semmes statue there, up close, than I would have out in the full sun of a humid Mobile afternoon.

It has left me with much to think about.

The Robert E. Lee of the sea. The Confederate Das Boot commander. Story of the CSS Alabama would make for a great Confederate Das Boot film. Make it happen Chris.

Semmes surrendered with Joseph Johnston in North Carolina in 1865. Interestingly, and likely anticipating that he might end up in trouble for his wartime naval activity, his parole with Johnston’s army was signed as both a rear admiral and brigadier general. He was actually arrested in late 1865 in preparation for a piracy trial, and Semmes had his lawyer persona ready with his parole as a general as proof that the US government said he could go home and remain unmolested so long as he did not violate said parole. Ultimately, just as Jefferson Davis was never brough to trial, Semmes was also released before a trial began.

Semmes was not a pirate in international law, at least as recognized by the British and they were the ones who counted. Great Britain (followed by other nations) recognized the Confederacy as a belligerent (but not an independent nation) engaged in a war. Among other rights, Confederates could commission warships and engage in commerce warfare according to strict rules distinguishing the activity from piracy. Their commerce raiders were scrupulous in obeying those norms. The U. S., of course, refused to accept that status, which became a major bone of contention with the British.

The British certainly had a stake in the matter of the Confederacy’s standing, though, so I take their judgement on the matter with a grain of (sea) salt. Of course, I readily admit I’m out of my depth on Confederate naval matters, so I can’t wade into the fine points the way you (or Neil) can!

The Sherman of the sea He destroyed the property of the enemy as Sherman destroyed the property of the rebels. Semmes didn’t make anyone walk the plank, anymore then Sherman massacred civilians. Semmes whined a bit after being defeated but that’s not a war crime

thanks Chris, great essay … it’s nice to see the City of Mobile did not to hide Semmes away in some dark warehouse … instead, they chose to display the statue in a less public locale with some nice curation … that’s the way to do it!

on the piracy charge, i am ruling Not Guilty … Semmes’ defense would likely be that he was an officer commanding a commissioned vessel in the navy of a belligerent power … and was engaged in commerce raiding, not piracy or privateering.

his lawyers might argue that commerce raiding was a legitimate strategy to interrupt and destroy United States war-time logistics by attacking enemy commerce at sea … Alabama and her sisters — Florida, Sumpter, Shenandoah, et al — didn’t commit piracy in the legal sense as they rarely, if ever, engaged in criminal acts by taking cargo as pirates do … nor did they act as a state sanctioned privateers taking prizes and adjudicating their legitimacy in an Admiralty court.

finally, Semmes was a stickler for the rules and only destroyed United States registered vessels carrying American cargo … if the skipper of American flagged vessel could prove to Semmes’ satisfaction that the vessel was conveying non-US owned cargo, he would bond the ship and release it … the bond would be the skipper’s promise, on behalf of the United States, to pay the Confederacy for the value of the ship at the end of the war … there are at least five instances of Semmes doing that

where the United States did have a legitimate beef was its claim against Great Britain for building Alabama and her sisters … the United States prevailed by arguing that Britain knowingly violated her own neutrality laws by providing armed vessels to a belligerent.

PS — Great pics as well … love the patina on the Admiral

Both Semmes and Waddell got warships named after them, which would never happen today. Waddell is problematic here in Hawaii as he captured ships flying the Hawaiian flag. He contended the registrations were improper, and the ships were properly American. There may be some truth to that but the reality is that Hawaii lacked the power to contest the capture.

i am sure there were other skippers who didn’t pass Semmes’ “paperwork sniff test” and had their ships burned … and since Semmes both seized the vessel and acted as his own Admiralty court, this wasn’t exactly an unbiased process.

we also had submarines named after R.E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, both decomissioned long ago … and currently two carriers named after gents with sketchy records on race — Carl Vinson and John C. Stennis

The irony is that Semmes has been twice “contextualized” to serve the ideologies of the moment. I’d have preferred to leave him where he was, and allow the public, over the chasm of 160 years, to educate themselves. Isn’t this a “pro choice” approach?

John, I’m doing research on the Semmes monument. Can you point me to any sources on the monument’s other two contextualizations? I would appreciate it!

Among those who went down with the Alabama was David H. White. In 1862 Semmes had captured a ship off the coast of Delaware–a slave state. Among the passengers aboard the ship was David White. Semmes offered White his freedom if he enlisted in the Confederate navy and White agreed. White was offered an opportunity to go ashore the night before Alabama’s final fight but refused and remained aboard, serving as a “powder monkey” carry8ng ammunition to one of the ship’s guns. White went down with the ship. So, Semmes was both a slave owner and an abolitionist, should we say in the “context”?

great point …when you look close, history gets mightly complex and historical figures often don’t fit in the neat little boxes — good guys & bad guys — we construct for them.

I appreciate what the Mobile History Museum did to preserve and contextualize the statue. In my opinion, that should be done with many controversial statues across the nation. Instead of blindly defending a local landmark without understanding its history, it should be put in a place where it can truly educate.