What If…George Thomas Had Marched Through Snake Creek Gap?

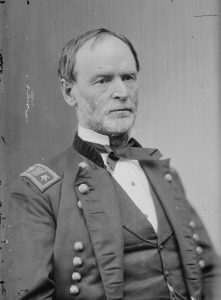

On May 7, 1864, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman set his three armies marching. At the time, they were stretched on a long front, from Red Clay on the Georgia-Tennessee line to Lee’s and Gordon’s Mills, more than a dozen miles to the southwest. Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield’s Army of the Ohio held the left (Red Clay), and Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland the center (Ringgold). Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee was on the right (Gordon’s Mills). Altogether they numbered 110,000 men. Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee held a line about seven miles long from east of Dalton and north of it, then southward along Rocky Face Ridge, ending at Dug Gap. He had half as many troops as Sherman, 55,000.1

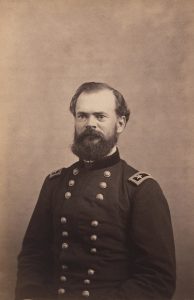

In late February, during demonstrations against the Rebels on Rocky Face, Thomas’ troops had almost broken through at Dug Gap before Confederates rushed reinforcements there. Thomas figured there were other gaps to the south, and there were, especially Snake Creek Gap, five miles south of Dug, which appeared undefended. This led Thomas to propose to Sherman in late March a plan for the upcoming campaign: Schofield and McPherson would demonstrate against Rocky Face, while he led his army through Snake Creek Gap, flank Johnston, perhaps cut the railroad in his rear, and force the Rebels to retreat or give battle.2

The plan promised success because of Joe Johnston’s myopia: “Snake Creek Gap was left totally unguarded,” as Connelly declares.3

Sherman liked Thomas’ plan, but only up to a point: he preferred that his friend “Mac” to lead the flanking column.

Cump and Pap had bunked together at West Point and it was there that Thomas earned his “Pap” nickname. He picked up another one there, too: “Slow Trot,” from the time when, as cavalry instructor, he had ordered some headstrong cadets to trot, not gallop.4

When secession neared, Sherman had a chance to ask his old roommate what he would do if his home state left the Union (Thomas was a Virginian). Came the quick answer: “I have thought it all over and I shall stand firm in the service of the government.”5

Later, when Thomas’ loyalty came into question, Sherman defended it, even before President Lincoln. In March of 1864, when Grant went east and Sherman took his place as commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi, Thomas may have felt slighted, but he said nothing about it. For his part Sherman shrugged off the idea of some sort of conflict. “Not a bit of it,” he said; “I would obey Thom’s order tomorrow as readily and cheerfully as he does mine today. But I think I can give the army a little more impetus than Thom can.”6

At the same time, Sherman liked McPherson and may have admired him as well, once calling him “a noble, gallant gentleman and the best hope for a great soldier.”7 McPherson’s star had risen fast in the west.. He was Grant’s chief of staff at Henry and Donelson; had fought at Shiloh; brigadier in mid-August ’62 and major general after Corinth. As commander of the XVII Corps he was with Sherman at Vicksburg, and when Sherman was kicked upstairs in March of ’64, Mac took his job as commander of the Army of the Tennessee, which brought him even closer to the new Military Division leader.

So the relationship between Sherman and McPherson was there, as was Sherman’s affinity for the Army of the Tennessee, which he had commanded from October 1863 to March of ’64. But Mac was inexperienced as army commander, having taken over on March 23, just six weeks before the campaign started. As John Scales observes, inexperienced army commanders tend to be cautious.8

Yet Sherman had instructed McPherson to be aggressive: “I want you to move…to Snake Gap, secure it and from it make a bold attack on the enemy’s flank or his railroad.” As it happened, McPherson’s two corps, the XV and XVI, on May 7 marched a half dozen miles south before camping. The next day Mac reached Villanow, just a few miles west of Snake Creek Gap. Pressing farther on the 9th, Federals approached Resaca, a railroad town sixteen track-miles south of Dalton. About 2 p.m. Mac sent a message to Sherman reporting his progress which led Cump to jump: “I’ve got Joe Johnston dead!” But just when his advance got a mile or two from the railroad, Mac lost his nerve. Enemy defenses looked strong. He didn’t know how many Rebels manned them (a brigade of cavalry). He wondered if the enemy would swoop down from the north and overwhelm his flank. So he ordered his troops back into Snake Creek Gap. At headquarters an obviously disappointed Sherman could only lump the news. When he and McPherson later met, Cump greeted him with “Well, Mac, you have missed the opportunity of a lifetime.”9

One may argue that Sherman should have known that McPherson might falter. To be sure, this was McPherson’s first major operation as commander of the Army of the Tennessee; he had been appointed just a few months earlier (succeeding Sherman). So he may be forgiven, one might suppose, for choking before the prize. Nonetheless, a month and a half later Sherman was still smarting over that lost opportunity, as he showed in a letter to General Grant, June 18:

My first movement against Johnston was really fine, and now I believe I would have disposed of him at one blow if McPherson had crushed Resaca, as he might have done, for then it was garrisoned only by a small brigade, but Mc. was a little over cautious lest Johnston, still at Dalton, might move against him alone; but the truth was I got all of McPherson’s army, 23,000, eighteen miles to Johnston’s rear before he knew they had left Huntsville. With that single exception McPherson has done well.10

Nevertheless Sherman got over it, and throughout the campaign continued to turn to McPherson and his army as his favorite force to flank Johnston out of position.

Historians have seen Sherman’s Snake Creek Gap maneuver as bearing enormous campaign-changing potential. “Sherman was disappointed in this, and when they met, told McPherson that he had lost a great opportunity” (Cox, 1882); “McPherson did not press on to Resaca, but halted, after going a short distance south of the gap” (Hay, 1923); “Sherman was furious” (Horn, 1941); he was “bitterly disappointed at McPherson’s failure” (Julian, 1964); “fortunately for the Southerners, more reinforcements arrived to obstruct McPherson’s march” (McMurry, 1982); “if the Federals can destroy this bridge [across the Oostanaula at Resaca] they will slice Johnston’s lifeline to Atlanta” (Castel, 1992).11

Well, historical writing can involve the use of imagination as part of the process of constructing a narrative. So let’s imagine what might have happened if a more experienced—and less cautious—general in Sherman’s army group had been in charge of the Snake Creek Gap maneuver.

…like George Thomas.

In late February, Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland engaged Johnston’s forces for several days of skirmishing along Rocky Face. In the process Federals learned of Dug Gap, a man-made pass five miles south of Mill Creek/Buzzard’s Roost Gap (through which ran the railroad to Chattanooga). The discovery led Thomas to wonder if there might be more passes farther south that could allow a Federal turning maneuver around Johnston’s left flank. Poring over maps, Thomas learned of Snake Creek Gap, a defile that led to Resaca, the Western & Atlantic, and Johnston’s rear.

A month later, after Sherman had succeeded Grant in charge of the Military Division of the Mississippi and had begun to plan his spring campaign into Georgia, Thomas proposed that he lead his army through Snake Creek Gap while McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee and Schofield’s Army of the Ohio demonstrated against Johnston’s front. Sherman liked the plan—but not Thomas’ role in it. Rather, Sherman designated McPherson’s army as the force of maneuver. On May 5, 1864, Cump instructed his friend Mac on what he was to do: march through the gap, pounce on the railroad near Resaca, wreck it, then withdraw back into the gap and wait for Johnston to start retreating—as surely he must.12

So Mac missed the opportunity of a lifetime, and I would argue that George Thomas would have done better. When he was lobbying Sherman for his army to conduct the Snake Creek march, Thomas outlined what he would do once he had pushed his forces through the gap: after he cut Johnston’s railroad, he expected that the Rebels would retreat—not southward, as the Army of the Cumberland would stand in their way, but to the east, “through a difficult country poorly supplied with provisions and forage,” as Thomas Van Horne writes in his early history of the Army of the Cumberland.13 In such a logistical plight, Thomas envisioned Johnston’s army breaking up or melting away. If it did not, Thomas foresaw attacking it and with his superior force, defeating it in open battle.

Moreover, we may surmise that George Thomas would not have choked. At Chickamauga he had earned his spurs, and won his fame, by refusing to follow the fleeing Rosecrans and half the army on the road back to Chattanooga. While it may be too much to credit Thomas with saving the Army of the Cumberland there, as even one of his early biographers admits, there is no doubt that his lapidary stamina prevented Chickamauga from becoming more of a Union disaster than it already was.14

That very lapidation demonstrated a calm in the storm, a refusal to flinch that eluded McPherson on May 9 before Resaca.

Second, he would have cinched the opportunity to shine, as he had done at Chickamauga. Given the opportunity by Sherman to possibly win the campaign with one bold stroke, there is no evidence that Thomas would have shirked or skulked. Recall that it was Thomas who had conceived the plan to flank Johnston out of Resaca; that eyes-on-the-ball resolve would have propelled him through Snake Creek Gap had he been given the chance.

Then, too, the men who followed the Rock would have demonstrated their own bravery and initiative. Recall that it was Thomas’ men who, without orders, charged up Missionary Ridge and routed Bragg’s line at its crest.15 Such soldiers would not falter when given another campaign-changing chance; the laurels won earlier by their courage, particularly of its impulsive kind, would likely have been on the minds of Thomas’ men that May day.

Finally, numbers. McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee started the campaign with 25,000; Thomas’ was more than twice that size. While it is true that the entire Army of the Cumberland could not have poured through Snake Creek Gap as fast as the Army of the Tennessee, enough of them, in the thousands, would have given Thomas the further confidence to face the Rebels ahead who spooked McPherson. Richard McMurry blames Sherman for sending McPherson to Snake Creek, not Thomas: “Any one of Thomas’ three massive infantry corps was almost as strong as McPherson’s total force.”16

With all of this in mind, the prospect that the course of the Atlanta Campaign could have been set before it began is a counterfactual possibility too dramatic for historians of the campaign to overlook. “In retrospect,” Dr. McMurry writes of Thomas’ possible coup, “we can see that, in all likelihood, his seizure of the gap [would have] determined the outcome of the campaign.”17

This is a good way to conclude. If seizing Snake Creek Gap and bottling up or battling Johnston’s hard-pressed army could have won Sherman the Atlanta Campaign at its virtual outset, George Thomas would stand among Union war heroes even taller than he actually does today. The Rock of Chickamauga could have been the Sledgehammer of Dalton.

————

Notes

1 Sherman to McPherson, May 5, 1864, Official Records, vol. 38, pt. 4, 39; Richard M. McMurry, Atlanta 1864: Last Chance for the Confederacy (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), 33-34, 38.

2 Stephen Davis, Atlanta Will Fall: Sherman, Joe Johnston, and the Yankee Heavy Battalions (Wilmington DE: Scholarly Resources, 2001), 35.

3 Thomas Lawrence Connelly, Autumn of Glory: The Army of Tennessee, 1862-1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971), 330.

4 Brian Steel Wills, George Henry Thomas: As True as Steel (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2012), 2, 17, 64.

5 Francis F. McKinney, Education in Violence: The Life of George H. Thomas and the History of the Army of the Cumberland (Chicago: Americana House, 1991 [1961], 100.

6 Ibid., 104, 282, 313.

7 Lloyd Lewis, Sherman: Fighting Prophet (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1960 [1932]), 299.

8 John R. Scales, Sherman Invades Georgia: Planning the North Georgia Campaign Using a Modern Perspective (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2006), 163.

9 OR, vol. 38, pt. 4, 39; Albert Castel, Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864 (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1991), 139, 141, 150.

10 Sherman to Grant, June 18, 1864, OR, vol. 38, pt. 4, 507.

11 Jacob D. Cox, Atlanta (Dayton OH: Morningside, 1987 [1882], 37; Thomas Robson Hay, “The Atlanta Campaign,” Georgia Historical Quarterly, vol. 7. No. 1 (March 1923), 22; Stanley F. Horn, The Army of Tennessee: A Military History (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1941), 323; Allen P. Julian, “From Dalton to Atlanta—Sherman vs. Johnston,” Civil War Times Illustrated, vol. 3, no. 4 (July 1864), 36; Richard M. McMurry, John Bell Hood and the War for Southern Independence (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1982), 102; Castel, Decision in the West, 137.

12 Castel, Decision in the West, 54, 121, 123.

13 Thomas B. Van Horne, The Army of the Cumberland (New York: Smithmark, 1996 [1875]), 361-62.

14 Van Horne, Army of the Cumberland, 282.

15 McKinney, Education in Violence, 296.

16 McMurry, Atlanta 1864, 65.

17 Ibid., 63-64.

I may be mistaken, but I believe that Johnston might have had to abandon most of his artillery if he fled East. I recall reading that there were no good fords for the guns in that section of the river. The war would have been over in 1864,

Great “What If”. A real missed opportunity.

Thomas’ scouts found the unguarded gap. He created the plan. He would have moved heaven and earth to make sure it succeeded.

Excellent, thought- provoking article… and the author, Steve Davis, provides an opportunity to reveal more information, relevant to “the Campaign in the West.”

Many do not realize how close U.S. Grant and James McPherson had become, after Henry Halleck “sent McPherson to keep an eye on Grant” during February 1862: Grant charmed Halleck’s spy; he “turned” McPherson from Halleck and incorporated the USMA Class of 1853 graduate onto his personal Staff, and then tested McPherson’s loyalty at Shiloh. And afterwards, Grant groomed McPherson for senior command in the Union Army. By the time of Vicksburg, the Union Team of the West was not Sherman & Grant, but Major Generals Grant, Sherman and McPherson.

Then, U.S. Grant departed for Washington and promotion to LTGEN. And just prior to commencement of the operation in Georgia, McPherson asked Sherman for a Leave of Absence in order to take care of personal business; but that request was ultimately denied… and events subsequently transpired as recorded, culminating with McPherson’s death in the field before Atlanta in July 1864.

Could George Thomas have accomplished the mission at Snake Creek Gap? Most certainly. However, LTGEN U.S. Grant had no intention of grooming MGen Thomas for increased responsibility within the Union Army.

“Could George Thomas have accomplished the mission at Snake Creek Gap? Most certainly. However, LTGEN U.S. Grant had no intention of grooming MGen Thomas for increased responsibility within the Union Army.”

Is this just George Thomas worship? Why would “LTGEN” Grant have any interest in “grooming” a general that had been around forever? Longer in the service than Grant. Why did Thomas need to be “groomed?” Was he still that inept after all those years of service?

In McPherson’s defense, I don’t think he had cavalry with him. That’s on Sherman, not him. Since he was moving blind, continuing the advance would have been a pretty big gamble. It’s an interesting point that Thomas probably would have made the advance, but he also had a much larger force. As the article points out, that again is on Sherman.

A cavalry division under Judson Kilpatrick was with McPherson. But Kilpatrick was wounded at Resaca. I’m not sure if he was wounded before or after McPherson missed his opportunity at Snake Creek Gap. But if it occurred before, the confusion that usually occurs when a commander is wounded or killed, could have made the cavalry recon less successful and helped to lead to McPherson’s cautious approach.

Really good article, learned alot, thank you for it. To Mr. Scales point, Ewell at Gettysburg?