What If James Longstreet Had Been at the North Anna River?

I’ve long maintained that James Longstreet’s wounding in the Wilderness had a bigger negative impact on the Army of Northern Virginia in the immediate moment than the wounding of Stonewall Jackson a year earlier at Chancellorsville. In fact, the wounding of Jackson when it happened may have been the most fortuitous accident that could have happened to Lee’s army (for more on that point, read here).

Longstreet’s wounding, in contrast, had no silver lining. It had several immediate, negative consequences and a negative long-term impact. I’ll touch on those momentarily, but one consequence I’ve been thinking about a lot lately has me looking down the road two and a half weeks beyond Longstreet’s fateful appointment along the Orange Plank Road.

As the night of May 23 turned into the morning of May 24, Robert E. Lee’s army reconfigured its defensive position along the North Anna River in one of the most inspired acts of improvisation in the entire war. The resulting position, an inverted “V,” forced the Federal army to advance across two fronts, separated by more than six miles and two river crossings. The farther each wing of the army advanced, the farther they both got from mutual supporting each other. It was the perfect trap. (Click here to read more about the inverted “V.”)

The Federal II Corps, in particular, found itself isolated along the Telegraph Road after crossing at the Chesterfield Bridge. It slowly advanced southward, finding only light picket resistance. Far ahead, the Confederate Second Corps waited in ambush while the First Corps lurked on the II Corps’ unprotected right flank.

Lee had the opportunity to crush this isolated Federal corps, sweeping it decisively from the field.

Yet his long weeks of little sleep and the open eruption of a percolating case of dysentery laid Lee low by mid-morning. Confined to his tent, the feverish Lee sounded delirious as he mumbled, “We must strike them a blow. We must never let them pass us again. We must strike them a blow.”

Lee was too ill himself to strike that blow. Of his three corps commanders, none held his confidence enough for him to entrust any of them to strike the blow, either.

First Corps commander Richard Anderson—Longstreet’s replacement—had only been in command for a couple weeks, and although he’d performed solidly enough at Spotsylvania, he was too green to take charge of a sweeping assault that required the coordination of most of the army.

Second Corps commander Richard Ewell—the second-in-command of the army by virtue of seniority—had lost Lee’s confidence after near-disastrous performances on May 12 and 18 at Spotsylvania. Like Lee, Ewell also had a case of dysentery coming to a boil. (Lee would make convenient use of Ewell’s illness just a few days hence as an excuse for replacing him.)

Third Corps commander A. P. Hill, the weakest of a weak lot, he just botched operations on the army’s left flank the night before. Hill had allowed the Federal V and VI corps to cross the North Anna rather than bottling them up at the river crossing. (Lee’s son, Rooney, was much to blame for this for providing Hill with poor intelligence, but Lee blamed Hill.)

And so I have been wondering: What if James Longstreet had been at North Anna? What if Lee still had his trust “Old Warhorse” available to take command of the army at a time when Lee could not command it himself?

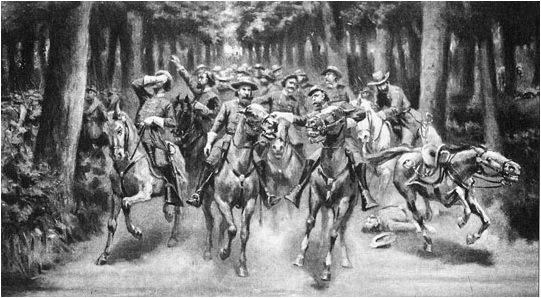

Longstreet had a talent for striking—devastatingly hard—the very sort of blow Lee had set up at North Anna. Look at Longstreet’s crushing blows at Second Manassas, Chickamauga, and the Wilderness. For that matter, look at the power of his strike on July 2, 1863, at Gettysburg. On May 24, 1864, the Army of Northern Virginia was poised to strike another hard hit, and Old Pete would have been the perfect commander to throw that punch.

Longstreet’s wounding on May 6 in the Wilderness was hugely detrimental to Robert E. Lee. It immediately sapped Confederate momentum in the middle of a crucial assault, giving Federals nearly four precious hours to fortify before Lee could send another wave forward—a wave that Federals successfully repulsed.

Longstreet’s loss also deprived Lee of vital insight into Ulysses S. Grant. Longstreet and Grant had served together in the prewar army and knew each other well. No one else in Lee’s army save Cadmus Wilcox (who had served with Longstreet and Grant) had that kind of personal first-hand knowledge about Grant. If Lee’s superpower was his ability to take the measure of his foes and then devise successful battle plans to foil those foes, that superpower utterly failed him with Grant, whom he misread over and over. Longstreet’s counsel would have been invaluable.

It’s impossible, though, to extrapolate events from May 6 in any way that reasonably puts Longstreet along the North Anna River on May 24. In the course of the Overland Campaign, those eighteen days were a lifetime. We would need Longstreet to escape injury and then have every other event take place in the exact same way for eighteen days in order to have Longstreet in a position to strike the blow. To expect such a sequence of events is to stretch credulity beyond its breaking point.

For instance, if Longstreet had not been wounded, then how would the assaults along the Orange Plank Road have played out on May 6? Would there have been a four-hour delay in the fighting? Would the Federals have been able to fortify their position? Would they have been able to maintain control of the Brock Road/Plank Road intersection? If not, Grant’s options for “no turning back” would become significantly altered—so would he move toward Fredericksburg? Or maybe toward Spotsylvania via the route the IX Corps ultimately took, bringing the army to the gates of the village from the northeast instead of the northwest? How would that have impacted the way the battle of Spotsylvania Court House unfolded—if the battle ever happened at all?

On the night of May 7, Lee ordered Longstreet’s replacement, Anderson, to start marching toward Spotsylvania at 2 a.m. on May 8. A forest fire in the area of the First Corps’ position promoted Anderson to instead move out at 10 p.m.—a four-hour head start that proved decisive for the morning battle in Spindle Field. Would an unwounded Longstreet have moved out early? Would there have even been a need to (considering all the questions I just mentioned in the previous paragraph)?

And so the list of contingencies goes on.

It’s like trying to plop Stonewall Jackson onto the July 1 battlefield at Gettysburg: too much could potentially happen in the two-month aftermath of Jackson’s wounding to realistically imagine him getting to Gettysburg in the first place. We can’t get Longstreet to North Anna, either, as intriguing as the scenario might be.

Considering Longstreet at North Anna does bring into sharper focus the leadership crisis Lee actually faced by mid-May 1864. He had long since become the Confederacy’s indispensable man. North Anna threw that reality into stark relief. No man, and no old warhorse, was able to step up and strike.

I have a better one for your ‘What if” category – What if, on May 31, 1862, Longstreet actually followed Joseph E. Johnston’s orders at Seven Pines?

Had Longstreet performed in the manner in which he was expected, his division would have smashed the right flank of the exposed IV Corps and then placed the III Corps in peril with its back to the flooded Chickahominy River.

According to Capt. George Mindil, then a staff officer of David Birney’s, wrote: “Had his [Johnston’s] plan been fully executed as to the time and place as contemplated; the left wing of McClellan’s army would have sustained irreparable disaster and the retreat of the whole army would have followed.”

Longstreet’s failure to enact Johnston’s desired plan resulted in a major lost opportunity for the Confederacy. One can only surmise the impact of a Federal disaster at Seven Pines, when combined with Stonewall Jackson’s successful Valley Campaign, would certainly have placed the politicos in Washington, DC into turmoil.

What if Chris Mackowski changed from a Jackson fanboy to a Longstreet fanboy. Now there is a “what if” that could happen? Just kidding. Great “what if” article, a lot to think about from the North Anna expert.

Ha ha ha! Funny thing is, a lot of people think you have to like Jackson OR Longstreet but that liking one has to bee mutually exclusive of liking the other. I actually like Jimmy Longstreet a lot–I have mad respect for him!

Nice to hear from you, Larry!

Excellent post! The one man who knew Grant the best was down two days into the Overland Campaign.

As a caveat to the what if/fantasy-football game….what if Longstreet would’ve been at the North Anna AND used George Pickett (who just rejoined the ANV at the North Anna) to snap the trap and lead a devastating charge that could’ve potentially crippled Hancock’s II Corps and redeemed himself. Grant’ed, Pickett had fallen out of favor with many by then. Still, something to think about.

There are more preservation opportunities at the North Anna. The Castle Glen Winery was selling due to covid losses and would make up the left flank of Wilcox’s division going into the Jericho Mill fight. Also, the farm field is up for sale across from the historic Dr. Miller house and between Ewell and Hancock’s Corps. So far, nothing has been saved east of the Jefferson Davis Hwy/Telegraph Road.

do we know if Lee arrayed his forces in the inverted V with the intent defeating the AOP in detail … or did the deployment of Federal forces so far apart offer this opportunity?