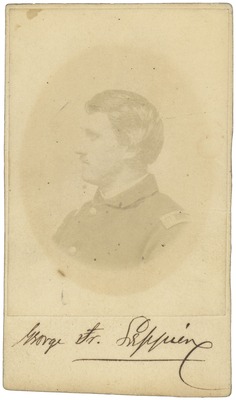

He Freely Gave Himself: George Leppien and His Maine Battery

In the midst of a growing crisis on the Army of Virginia’s left flank, a battery of Maine artillerymen trotted to the top of Chinn Ridge. The trained gunners unlimbered their pieces and prepared their guns to open on the nearby enemy. They fought for time, and suffered for it. But their commander, George Leppien, prepared them for this moment, even if sickness prevented him from being with them this day.

George Leppien was born in Philadelphia 1836 and spent his early youth in his native city. Leppien was born to a German immigrant father who had become a successful businessman in Philadelphia. George’s father believed his only son “should have the highest advantages for culture and improvement,” and he had the means to make that happen.

From 1845 to 1859, George Leppien schooled in Europe, including getting a five-year education at a Prussian military school. By the end of the 1850s, a learned George Leppien returned to the United States. Sadly, shortly after he did, his father died. To keep his family financially afloat, Leppien shouldered running his father’s business, a venture that he did not want to take on but his sense of duty to his family convinced him to.

The start of the Civil War two years later gave Leppien an outlet. Despite his extensive time spent overseas, “His feeling of nationality was intense—for from childhood’s years he had stood as a type of Americanism among his school fellows in a foreign land—and at once, without waiting for the aids and influence to give him a proper command, rushed to the defence of the nation’s flag.” Leppien briefly served as a second lieutenant with the 15th New York Heavy Artillery until November 1861.

Maine’s governor Israel Washburn, Jr., was busily raising troops from his state to defend the Union. When Washburn began work to piece the Fifth Battery, Maine Light Artillery together, he wrote Army of the Potomac artillery chief William Barry asking for an officer with military experience to command it. Barry replied that he could not currently spare such an officer. However, he did send Washburn Leppien’s name, a man in Barry’s estimation who “would answer the desired purpose as well as a West Point graduate.” One of Washburn’s Washington agents interviewed Leppien, was impressed, and forwarded him to Maine to report for duty. On November 18, 1861, Leppien was commissioned as the battery’s captain.

Leppien quickly molded the battery in his vision. “As a camp disciplinarian, as a scientific and practical artillerist, as commander of a Battery in the heat of action, he was everywhere the model soldier,” one newspaperman said. Despite the strict discipline he demanded of his men, they respected him. During Leppien’s time training in Maine, he gained many friends in the state and likewise earned their admiration. Leppien’s work paid off. When the battery joined the Army of the Potomac, its artillery chief declared, “no better battery than Leppien’s could be found in the U.S. service, either volunteer or regular.”

The discipline Leppien instilled in his men served them well on many battlefields, even when Leppien could not personally be with the battery. At the Battle of Second Manassas on August 30, 1862—where I first encountered Leppien’s name—Leppien could not lead his men into battle atop Chinn Ridge due to “a local affliction” which made it “impossible for me to remain in the saddle,” Leppien wrote in his unpublished after-action report. Command passed down to Lt. William F. Twitchell.

In the fight to buy more time to allow his army to withdraw across Bull Run and escape the attacking Army of Northern Virginia, Maj. Gen. John Pope fed any forces he could spare to Chinn Ridge on the afternoon of August 30. Armed with Leppien’s discipline, Twitchell’s leadership, and four guns, the Maine artillerymen trotted through the ranks of the 88th Pennsylvania and went into battery 200-300 yards north of the Chinn house. The advancing enemy was just 150 yards from the battery, but the disciplined Mainers rammed rounds of canister into their pieces to check the enemy. These blasts only slowed the Confederate assault. Lacking support, the artillerymen continued to load and fire. However, “in the short space of seven minutes,” wrote one battery member, “the conflict was over, the horses being killed, the guns were taken, and the enemy advancing drove everything before them.” Leppien’s men, like the thousands of other Federals on Chinn Ridge, did whatever they could and stood against an overwhelming enemy onslaught to buy time for the rest of the army. Leppien’s command lost 3 men killed, 11 wounded, and 2 missing in the quick struggle. One of the dead was Leppien’s replacement, 35-year-old William Twitchell.

Despite the losses suffered at Second Manassas, Leppien’s battery rebounded. By the winter of 1862-63, it was “first on the list of the eighteen best drilled batteries in the Army of the Potomac in the winter of 1862-63,” remembered a battery member. Leppien himself served as James B. Ricketts’s Chief of Artillery. Ricketts and his officers suggested to Maine’s governor Abner Coburn that Leppien should become a lieutenant colonel of Maine artillery. The commission did not become official until May 18, 1863. By that time, Leppien was fighting for his life.

On May 3, 1863, Leppien personally led the battery he molded into combat. Positioned near the Chancellor House, they suffered greatly. Six of the battery’s members were killed while 22 were wounded. Additionally, 43 of the battery’s horses died. While shouting orders to his battery, he was hit in the left leg and carried alive from the field. The wounded Leppien ended up in a hospital in Washington, where his leg was amputated. On his deathbed, he received his promotion to lieutenant colonel before expiring on May 24, 1863.

Despite being a Philadelphia native—his remains rest there today—and an internationally educated soldier, Leppien identified with Maine. He was fond of the state’s people and proud of his connections to them and to the state. He claimed the accolades he won were due to “those brave boys” of his battery that went on to fight at Gettysburg and beyond.

Mainers honored their adopted son. Grand Army of the Republic Post #136 in Stoneham, Maine was named in memory of Leppien. After the war concluded, Leppien’s mother gifted his sword to Maine’s sitting governor “to be preserved in the archives of the State.” One Maine newspaper editor eulogized the fallen artilleryman: “Possessed of all that could make this world desirable—wealth, culture, social position, grace of bearing, manly beauty, personal popularity—he yet accounted them all as nothing and freely gave himself to the cause which he regarded as the highest and the holiest.” Leppien also gave his life to train others to fight for the same cause. It showed on many battlefields, including 160 years ago at Chinn Ridge at the Battle of Second Manassas.

Kevin: Thanks for this informative article. Ironically, when Leppien went down at Chancellorsville, his place was temporarily taken by Lt. Edmund Kirby of Battery I, 1st US. Kirby was then MW and was promoted to Brig. Gen. on his deathbed.

One of many who fought and died to preserve the Union. A true patriot! What a shame it is again being torn asunder.

I appreciate the information about Leppien’s formative years and thank you for detailing the 5th Maine Battery’s experiences at Second Manassas.

Hello from a resident of Maine. Thank you for writing about this brave soldier.

My absolute favorite CW unit! Thanks for this article about this unsung but excellent artillery unit!

Lt. Edmund Kirby was tasked with extricating the 5th Maine Battery from the Chancellorsville clearing on May 3 because all the officers in the battery were killed or wounded, including Leppien. Kirby left his command and was in the process of supervising the task when a shell exploded nearby, wounding him. Both Kirby and Leppien had legs amputated in the subsequent days and they died four days apart, Kirby receiving a deathbed promotion to brigadier general.