A Slave Ship Crewman in the 8th Ohio at Antietam?

On September 16, 1862, a man in a Union blue coat hid in the ranks of the 8th Ohio Infantry Regiment. If the stories he had told his friends were true, he could have been indicted by a Federal court for taking an active role in human trafficking — specifically, the importation of African slaves. Four years early, on September 16, 1858, the slave ship Wanderer had arrived at the entrance to the Congo River, and he claimed he had been a crewman.

His comrades in the 8th Ohio knew him as Jack Sheppard. To one of his closer friends in the regiment, Thomas Francis Galwey, Sheppard confided a different story. Galwey apparently believed his friend’s tale or at least was curious enough to record it in his diary:

“Jack Sheppard’s real name was Victor Aarons. He was a full-blooded Jew. At eleven years of age he had shipped as a common sailor and had led a life of adventure until he enlisted with us in the summer of 1861. He had made several voyages on board a slaver to the coast of Africa. He had been involved in a mutiny on board the bark Wanderer, was captured with his associates by an American man-of-war, and brought in irons into the port of New York. Here he was imprisoned, but in some way or other succeeded in escaping from the hands of the law. On his way to a brother in Nashville, Tennessee he met a party of boon companions, recruits of ours, with whom he enlisted.”[i]

While Galwey’s summary is not as clear as a researcher might wish, the name of the ship Wanderer catches the eye. Is it possible that a crewman from the second-to-last known slave ship to land on United States shores fought in the ranks of the 8th Ohio Infantry at Antietam?

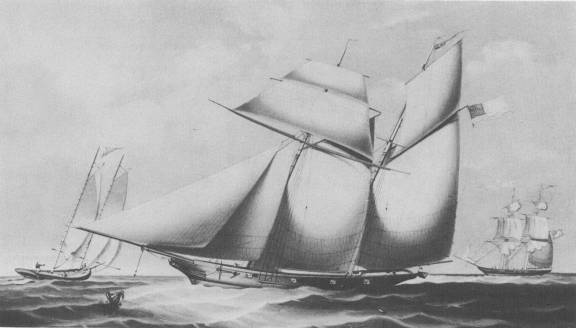

First, a little background on the Wanderer… Ship owner William Corrie from Charleston, South Carolina and Charles Lamar of Savannah, Georgia, hatched a scheme to send convert a luxury sailing vessel into a slave ship, sail to the west African coast, and return to a southern port with human cargo. Everything about the scheme was illegal. The United States had outlawed the importation of slaves since 1808, but since that time, some southerners had been talking about the possibility of reopening the slave trade and making it legal again.

Lamar refitted the Wanderer in New York harbor and somehow the ship passed inspections, despite additions that indicated the likely transport of hundreds of passengers which theoretically should have been red flags.[ii] The Wanderer stopped in Charleston harbor and took on pine boards which the crew would construct into additional narrow decks once the voyage started. In the summer of 1858, the ship left South Carolina and sailed to Africa. On September 16, 1858, the Wanderer arrived at the mouth of the Congo River and shortly after, Lamar contacted Captain Snelgrave who operated for an illegal New York-based slave trade company; Lamar arranged to purchase approximately 500 slaves, paying approximately $50 per individual.[iii] Nearly a month later, the human cargo had been delivered to the ship, and the return voyage started.

Few details are known about the Wanderer’s transatlantic crossing. However, by the time the ship arrived at its clandestine location on Jekyll Island, Georgia, 78 of the enslaved Africans had died. The horrors for those in bondage must have been similar to what occurred on other middle passage voyages, and the captain and crew likely acted with similar callous cruelty. News of the slave ship’s arrival leaked, but not until after the enslaved individuals had been sold. Importing slaves was a crime and eventually authorities also discovered falsification on the ship’s records, leading to the imprisonment of Lamar, Corrie, and other conspirators on charges of piracy in May 1860. However, a local jury in a Federal court in Georgia found them “not guilty.”[iv]

The Wanderer was taken into slave trading again, however. In November 1859, a crew numbering 27 men stole the ship, while the port authorities looked the other way. The ship sailed to Africa again. Approaching the African coast, the first mate instigated a mutiny, claiming that he had been forced onto the ship. The mutineers cast the captain adrift, and then the first mate sailed to Fire Island, New York, then to Boston where he turned over the ship to Federal officers on December 24, 1859. Ten men were imprisoned, but those who claimed they had been forced to crew the ship were allowed to go free. “Victor Aaron” does not appear in the list of crewmen printed in the early reporting by the abolitionist paper The Liberator.

While there are some detail discrepancies between the history of the Wanderer and what Galwey wrote about in his diary. But there are a few piece of evidence to consider when questioning if Sheppard could’ve been telling the truth.

First, the regimental historian of the 8th Ohio confirmed the alias name. In the regiment’s roster for Company B, “John Shepherd” appears with the statement “Killed at Antietam, Sept. 17, ’62.” But there’s an asterisk beside the name. At the bottom of the page, there’s a note: “This man’s true name was Victor Aaron, as the writer afterwards learned from his brother of Nashville, Tennessee.”[v]

This suggests that Sheppard was an alias and that the officers did not know about it during his enlistment. It also corroborates the fact that there was a brother who lived in Nashville.

Sheppard’s tale gets confusing that he made “multiple voyages” unless he means the two of the Wanderer. It’s entirely possible that he could have been involved in other nations’ slave trading voyages. Or he could have been on other American attempted voyages that were either not made or not completed. It’s also interesting that he said he was taken to New York by a warship. Online archived newspapers did not give results for the name “Victor Aaron” and his name was not listed among the crew that arrived in Boston. Of course, he could have been using a different name or perhaps had already made his escape.

Whether or not Sheppard got his details right (or Galwey recorded them correctly), it begs the question: is some or all of it true? The counter question: would someone what to lie about this? Would someone risk claiming to have committed a Federal crime as a joke? Would lying about this have somehow raised Sheppard in the eyes of his comrade? It seems unlikely. Even Galwey later wondered in his diary if Sheppard had been “guilty of great crimes.”[vi]

Another question rises: why would Sheppard have told Galwey about his real name and his past? Galwey makes no mention of remorse in his comrade. It comes across more like the later-recorded notes from a conversation tinged with “you won’t believe this!” Maybe it made Sheppard feel better in some way to tell about his past?

A few weeks prior to the battle of Antietam, Galwey wrote in his diary about the company’s lack of clean clothes. “We are very dirty and very lousy. The shirts we have on our backs now, we have worn for about a month.” As tormented as all the men were by these bugs, one fellow had a strange solution: “While I was on picket one night, one of my men, a hard case but a jolly fellow, Jack Sheppard, amused himself by stringing vermin on needle and thread for a necklace, gathering his jewels from the inside of the ankles of the men’s pantaloons.”[vii]

Two days before the battle, Galwey and Sheppard went foraging before the regiment reached Boonsboro. Galwey scrounged potatoes, but Sheppard returned with a duck. “So we have dinner. Forward again.”[viii]

On September 17, the battle of Antietam swept across the Maryland farms along the infamous creek and at the outskirts of Sharpsburg. The 8th Ohio was one of the early regiments to attack toward the Confederate position in the Sunken Road.

“General Kimball, our brigade commander, riding along the line, says “Now boys, we are going, and we’ll stay with them all day if they want us to!” Forward we go over fences and through an apple orchard. Now we are close to the enemy. They rise up in the sunken lane and pour a deadly fire into us. Our men drop in every few files. The ground on which we are charging has no depression, no shelter of any kind. There is nothing to do but to advance or break into a rout. We know there is no support behind us on this side of the creek. So we go forward on the run, heads downward as if under a pelting rain…”

“About fifty yards on this side of the enemy’s improvised trench in the sunken road is a slight elevation. Here we halt. The ground is covered with a soft turf speckled with white clover. To our right is Caldwell’s brigade. To our left, comes shortly Meagher’s Irish brigade. Beyond (south) of the sunken lane rises a low ridge. This ridge is a cornfield, and just back of it we can see the tops of the trees of an orchard. Line after line of the enemy’s troops are advancing along the ridge, through the corn. They come up opposite us and sink out of sight in the sunken lane. It is a mystery that so many men could crowd into so small a space. In the meantime the work of death and destruction goes on. Two Irishmen are carrying the colors of our regiment today. Sergeant Conlon has the battle flag and Corporal Ready the National Colors. By some miracle these two men, whose bravery is conspicuous, escape all injury. But our men are falling by the hundreds. Our brave Orderly Sergeant, Fairchild, sticks doggedly to his position, his face streaming blood. Jack Sheppard, my old mess-mate, jovial companion, and favorite with everyone, drops. He is shot in a dozen places. He never even groaned! Poor boy! This morning he boastingly said that the bullet was not yet struck that was to kill him!”[ix]

Sorrowfully, Thomas Galwey closed his thoughts on “Jack Sheppard” or Victor Aaron’s life. “So died “Happy Jack.” He had, perhaps, been guilty of great crimes. Perhaps not. During my acquaintance with him, I found him to be a brave, generous, and conscientious fellow. Full of honor, and as gentle as a woman. I couldn’t help forgetting the battle for the moments I thought of the loss of my friend.”[x]

Galwey seemed unsure about the truth of his friend’s life prior to his enlistment in the 8th Ohio. There are hints that he was uncomfortable if the story were true. It may be one of those historical stories that can never quite be proven true or false. Just a huge lie to pass away bored hours? Or a dark, dark truth?

If Sheppard’s story was true, then a former crewman from the second-to-last known slave ship to land on United States coast marched and fought in the ranks of the 8th Ohio Regiment. If it is true, then a slave trader wearing a blue uniform died in front of Antietam’s Sunken Road in the battle that led to the promise of freedom with the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

Sources:

[i] Galwey, Thomas Francis. The Valiant Hours; Narrative Of “Captain Brevet,” An Irish-American In The Army Of The Potomac (p. 56). Golden Springs Publishing. Kindle Edition.

[ii] Rohrer, Katherine. “Wanderer.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Sep 24, 2020. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/wanderer/

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Franklin Sawyer, A Military History of the 8th Regiment Ohio Vol. Infantry: Its Battles, Marches and Army Movements (1881). Page 201. Accessed through Google Books.

[vi] Galwey, Thomas Francis. The Valiant Hours; Narrative Of “Captain Brevet,” An Irish-American In The Army Of The Potomac (p. 56). Golden Springs Publishing. Kindle Edition.

[vii] Ibid., 46.

[viii] Ibid., 50-51.

[ix] Ibid., 55-56.

[x] Ibid., 56.

This is an engaging story that adds to the history of the Civil War. Thank you!

What a great find! Thanks for sharing.

What an odd story. Thanks for sharing it.

great story and another fine example of slick detective work by ECW historians … i am pressing the “i believe button” on the veracity of your primary source … thanks!

Sarah has provided more interesting information on the very interesting 8 OH. Incredible to think of the regiment’s duty at Sunken Road @ Antietam and Pettigrew-Trimble’s Flank on July 3 @ Gettysburg.