A Revenge Killing on Sherman’s March

ECW welcomes guest author Brian Krasielwicz

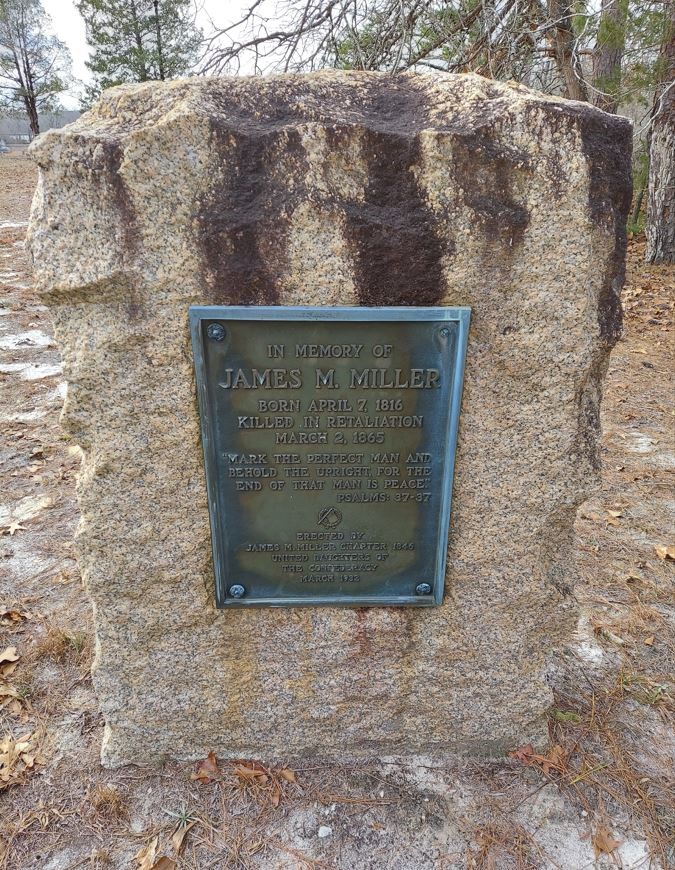

Five Forks Cemetery is situated about six miles south of the North Carolina state line, surrounded by a patch-work of farmland and crisscrossed by a tiny stream known locally as Little Fork Creek. The weathered headstones of the cemetery lack uniformity and the graves are seemingly placed at random within a tiny field that is surrounded by a chain-link fence. If it was not for the aluminum flagpole and the American flag gently rolling in the breeze, it would be easy to drive by this cemetery without even noticing it. Even more inconspicuous is a stone marker that sits just outside the cemetery fence near the edge of a copse of trees. The marker indicates the burial place of a James M. Miller and the story behind how he ended up near this otherwise unremarkable cemetery reveals a little-discussed piece of Civil War history.

On February 17, 1865, Columbia, South Carolina, formally surrendered to General William T. Sherman’s advancing Union Army. Confederate defenders, mostly mounted soldiers under the command of the newly promoted Lieutenant General Wade Hampton III, skirmished with the vanguard of the federal army for several days before finally retreating in the face of overwhelming numbers. Their withdrawal left the city unoccupied. Within hours of the Confederate evacuation, one-third of Columbia was on fire. Significant evidence exists to indicate that these blazes were lit by retreating Confederate soldiers in order to deprive their Union counterparts from obtaining cotton and other war materials, although it is likely that federal looting and copious amounts of suspiciously available alcohol also contributed to the conflagration.[1]

Regardless of who was ultimately responsible for the inferno, the destruction of Columbia outraged southerners and seemed to validate the brutal reputation that Sherman held throughout the Confederacy. Much of the vitriol directed at the Yankee army was a result of his “bummers” or foraging soldiers who ransacked southern homes and farms in search of food and other materials which they confiscated for the Union war effort. This looting and foraging also took place during the Union occupation of Columbia and wild stories of barbarous behavior told by frightened residents spread quickly throughout the surrounding areas. Mary Chesnut, a resident of nearby Camden, South Carolina, and wife of Confederate Brigadier General James Chesnut, wrote of one particularly disturbing incident in her diary on March 5, 1865. In the entry, she recalls a story that was told to her by her husband following the fall of Columbia. He had stopped at the residence of a woman and her young daughter who lived along the path of the Confederate retreat. James suggested that the woman’s daughter be sent away from the approach of the federals but the defiant daughter refused to leave her mother’s side.[2] That evening, when Confederate General Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry troopers joined Chesnut’s camp northeast of Columbia, they told James of the “horror and destruction” they passed that day and of “the outrage” that was done to the woman’s daughter by seven blue-clad soldiers. Wheeler’s men reported that they went off in pursuit of the daughter’s assailants “overtook them, cut their throats—and marked up their breasts, ‘These were the Seven.’”[3]

A footnote to Mary Chesnut’s diary, written by the editor offers this curious addition to the tale: “[a]ngered by the death of Union foragers in incidents such as the one [James Chesnut] describes… Sherman wrote Wade Hampton on Feb. 24, 1865, threatening to execute a Confederate prisoner for each Federal killed. Hampton responded the next day in a letter promising the execution of two Union prisoners for each Southern prisoner killed, condemning the foragers as ‘thieves’ justifiably murdered, and accusing Sherman of ordering the burning of Columbia. Sherman did not reply, and no executions took place.”[4]

A review of some additional source material provides conflicting evidence of the claim that no executions happened following this back-and-forth between the generals. Alonzo Brown, a soldier serving in the 4th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry of the Federal Fifteenth Corps wrote in a diary entry from February 25, 1865 that: “[s]ome of our men who were captured while out foraging had their throats cut and a label appended to their bodies upon which was written, ‘Death to all foragers.’ In retaliation for these murders, two of the rebels whom we had taken during the attack were immediately tied to a tree and shot. This was done by the order of the general commanding.”[5] Indeed, as the footnote to Chesnut’s diary entry states, a communication was sent by Sherman to Hampton on February 24, 1865. The message advised him that “[i]t is officially reported to me that our foraging parties are murdered after capture and labeled ‘Death to all foragers.’ One instance of a lieutenant and seven men near Chesterville [possibly the same seven soldiers referenced in the story told by James Chesnut], and another of twenty ‘near a ravine eighty rods from the main road’ about three miles from Feasterville. I have ordered a similar number of prisoners in our hands to be disposed of in like manner.”[6] Sherman wasn’t bluffing. He sent a communication to Major General Oliver O. Howard, in command of the army’s right wing, instructing him to “take life for life, leaving a record of each case.”[i][7] Hampton responded to Sherman’s threat on February 27, 1865, calling the Yankee bummers “thieves” and stating his resolve to execute two Union prisoners for “every soldier of mine ‘murdered’ by [Sherman].’”[8]

It is after this exchange that a report exists of a group of Union foragers from the 46th Ohio led by a Sergeant Woodford who “kidnapped a slave who retaliated when Woodford took an after-dinner nap by crushing the sergeant’s head with a lightwood knot.” The report continues that “Sherman ordered prisoners to cast lots to be shot, in accordance with his warning.”[9] A different report of the event disputes this soldier’s identity and instead indicates that the unlucky bummer was “a member of the 30th Illinois [who] was found with his skull bashed in.” It adds that: “[u]pon his body lay a card with the warning to foragers. Through his adjutant, Colonel Cornelius Cadle Jr., [Union General Francis P. Blair of the Seventeenth Corps] ordered General [Manning] Force to retaliate by shooting one of the two hundred prisoners he had taken.”[10]

There is some disagreement about what happened next. According to Colonel Cadle, the prisoners “drew slips from a hat. One had a cross on it. About halfway through the process a private from North Carolina threw up his hands and shouted ‘I have it.’” The soldier was described as a man “[o]ver six feet in height and about thirty-five years old… a good old grey haired man, the father of nine children…”[11] Burke Davis’s well-researched exploration of Sherman’s March indicates that “A gray-haired old man named Small drew the black-marked slip.”[12] Other reports indicate that the Confederate prisoner with the unlucky lot was a younger man and that it was “another prisoner, James Madison Miller,” also described as an older man with nine children, who “stepped forward and volunteered to take the younger man’s place.”[13] If it was, indeed, James Miller who was executed by General Force’s men (possibly taking the place of a soldier by the name of Small), his gravestone indicates that he was forty-nine years-of-age and not thirty-five as Colonel Cadle wrote. However, all accounts are in agreement that at the end of the process, the prisoner was shot and killed. One report indicates that Miller “was buried with a lightwood knot at his head” a memento that would have reflected the murder implement used on Sergeant Woodford.[14] In a concluding note, a Union soldier who witnessed the event wrote in his diary that the executed prisoner was “40 years of age and the father of a numerous family.” According to the same soldier “[o]n visiting his grave afterward I found the following inscription: ‘James M. Miller Co. C Browns Batt. S.C. Infy. Who was shot to death in retaliation for a regularly detailed forager who was murdered and found near Big Lynch Creek S.C., March 2nd 1865.”[15]

The tombstone inscription referenced by the Union soldier is long gone. It has been replaced by a new stone with a plaque that was dedicated by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in March of 1932. The new plaque contains the shorter message: In Memory of James H. Miller, Born April 7, 1816, Killed in retaliation, March 2, 1865. Following this death, the killing of bummers largely dissipated.

While the available evidence regarding these revenge killings isn’t completely consistent, it seems fair that a few conclusions about this event can be reached. First, the burning of Columbia and the fears of a marauding Yankee army generated persistent rumors about Union soldiers inflicting outrages on the nearby civilian population. It is also likely that some of these unsupervised soldiers did commit depravations. Whether the specific incident referenced by James Chesnut actually happened is unknown but it is probable that Confederate cavalrymen believed the assault took place and that the shooting of federal soldiers who were suspected to be guilty of crimes ranging from foraging to rape and even murder was deemed to be legitimate behavior. In addition, it is evident that reports of brutality and these retaliation killings found their way to the desks of the commanding officers, as the messages between Sherman and Hampton demonstrate. However, it is unclear if James M. Miller, a Confederate prisoner at the time of his execution, was selected for his fate by an unlucky lot or whether he instead sacrificed himself to save the life of a fellow soldier. What is certain is that the story of his death and the role it played in the Civil War can still be found on a stone near a remote cemetery that history has largely overlooked.

Brian Krasielwicz lives in Carrollton, Georgia and has a Master’s Degree in Public Administration from Walden University. He spent the last 30 years studying the Civil War and travelling to battlefields through the south. Brian has a fiction novel called “Marsupial Tracks” that is being published by Austin MacCauley and will be available for sale in the next few months.

[1] Hirshson, Stanley P. The White Tecumseh. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1997, pp 281-283.

[2] Chesnut, Mary. Mary Chesnut’s Civil War. Ed. C. Vann Woodward. New Haven: Tale University Press, 1981, p. 745.

[3] Chesnut, Mary. Mary Chesnut’s Civil War. Ed. C. Vann Woodward. New Haven: Tale University Press, 1981, pp. 745-746.

[4] Chesnut, Mary. Mary Chesnut’s Civil War. Ed. C. Vann Woodward. New Haven: Tale University Press, 1981, pp. 745.

[5] Brown, Alonzo Leighton. History of the Fourth Regiment of Minnesota Infantry Volunteers During the Great Rebellion 1861-1865. St. Paul: The Pioneer Press Company, 1892, p. 380.

[6] “Correspondence Between Gen. Sherman and Gen. Hampton.” The New York Times 13 March 1865, p. 1.

[7] Howard, Otis Oliver. Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard, Major General, United States army: volume 2. New York: The Baker & Taylor Company, 1987, p. 130.

[8] “Correspondence Between Gen. Sherman and Gen. Hampton.” The New York Times 13 March 1865, p. 1.

[9] Cromie, Alice Hamilton. A Tour Guide to the Civil War. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. Inc., 1975, p. 277.

[10] Hirshson, Stanley P. The White Tecumseh. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1997, p. 287-288.

[11] Hirshson, Stanley P. The White Tecumseh. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1997, p. 288.

[12] Davis, Burke. Sherman’s March. New York, New York: Random House, 1980, p. 104.

[13] Roden, C. W. “A Final Act of Retaliation — The Execution of James M. Miller CSA.” Southern Fried Common Sense, 12 March 2015, https://southernfriedcommonsense.blogspot.com/2015/03/a-final-act-of-retaliation-execution-of.html. Accessed 21 January 2023.

[14] Cromie, Alice Hamilton. A Tour Guide to the Civil War. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. Inc., 1975, p. 277.

[15] Roden, C. W. “A Final Act of Retaliation — The Execution of James M. Miller CSA.” Southern Fried Common Sense, 12 March 2015, https://southernfriedcommonsense.blogspot.com/2015/03/a-final-act-of-retaliation-execution-of.html. Accessed 21 January 2023.

I find it difficult to tease out what actually happened from the many reports some at second or third hand

There was a Catholic convent in Columbia. Sellina Bollin, then 17, was a student at the Ladies’ Ursuline Convent. Later, she would write her memory of that awful day when Sherman came to town. Toward nightfall, the Mother Superior, Baptista Lynch, went up the cupola of one of the convent buildings. Mother Superior Lynch was born Ellen Lynch in South Carolina to Conlaw Peter and Eleanor McMahon Lynch of County Monaghan, Ireland.

Earlier that day, Mother Superior Lynch had received written assurance form Gen. Sherman that the convent would be safe. Mother Superior Lynch and her brother, Fr. and later Bishop Patrick Lynch knew Sherman from their days in Ohio and Kentucky teaching in other Catholic schools. But, she saw something from that cupola, because she burst down the stairs saying the convent was doomed.

The sisters bundled the girls in nun habits against the cold air. By this point, most of the city was on fire. They proceeded to lead the students out of the convent. Fr. Jeremiah O’Connell led them out of the building complex.

Just before the school girls and the sisters left the Convent, a crowd of soldiers broke down the chapel door. They entered the sanctuary. One of the students, Sara A. Richardson would later recall that riot in the church: “While we were down on our knees, we were brought standing by the most unearthly battering in of the chapel door behind us, and rushed by a stairway from the Main street side. It was like the crush of doom. Drunken soldiers piled over each other, rushing for the sacred gold vessels of the altar, not knowing they were [already hidden].”

The altar vessels had already been secreted against this very event by a priest. The church was saved by the intervention of some of the soldiers. But, the Convent was destroyed. It was plundered first, before it was torched by the soldiers

Sara Richardson recorded that they could see soldiers with torches firing the roof of the convent. Some of the soldiers asked the sisters and pupils, “What do you think of God now? Is not Sherman greater? Do you think now you are sanctified? We are as sanctified as you.”

The next morning as the Federals were riding through the remains of the city, Mother Superior Lynch recognized Gen. Sherman. She confronted him about the plight of the now homeless sisters and their pupils. She reminded the general of his promise to protect the Convent. She managed to get the general to agree to allow the sisters the use of one of the few homes still standing.

Tom

Hard to press “Like” for this horribly sad article, but I do appreciate it!

” Significant evidence exists to indicate that these blazes were lit by retreating Confederate soldiers in order to deprive their Union counterparts from obtaining cotton and other war materials” Come again? Eyewitness testimony says the cotton was fine when the Confederates left.

Tom