Surviving Spotsylvania

Sometimes death creeps too close. Sometimes real-life fears grow out of proportion. While I would never intentionally minimize the loss, suffering, and sacrifice connected to Civil War battles, I had to try to shift perspective slightly this week when approaching the anniversary of the battle of Spotsylvania Court House. Instead of focusing on the dead from Spotsylvania’s fields and hospitals, I needed to focus on some stories that ended with continued life.

Total casualties of this shifting colossal battle—fought May 8-21, 1864—numbered more than 30,000. But what about the soldiers who were injured and survived. What was it like to be wounded…but survive Spotsylvania?

Keyword searching through the volumes of The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion offered some stories. These volumes can be gloomy and gory reading, but the compilation of records in itself was an attempt to show life-saving learning. Among the medical cases of soldiers who died of their Spotsylvania wounds, there are also accounts of men who lived. Touched by war, but able to live on—many of them to longer, full lives. Here are a few that I found…what’s a good word? Hopeful, perhaps?

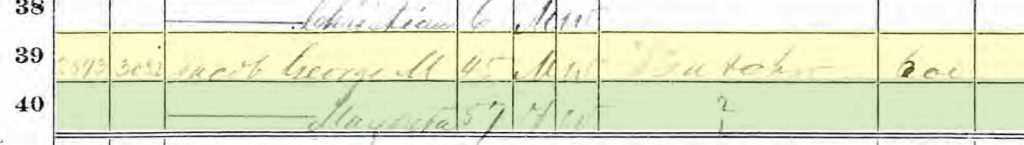

Thirty-nine year old Private George M. Jacob of Company D, 8th Maryland Infantry suffered a “gunshot wound of the right wrist, grazing bones of forearm” on May 8, 1864. Four days later he arrived at Fairfax Seminary Hospital, and on June 17, received a medical furlough, then a medical discharge from military service. In 1866, a medical examiner for Jacob’s pension application noted that the “ball fractured the radius near the wrist joint; a considerable portion of bone was lost. The wound has now closed, but several sharp spiculae of bone are embedded in the callus, their ends protruding in such a way as to interfere with the proper action of the muscles; the right hand is consequently almost useless.” Despite the after effects, Jacob had survived, and the later he received a pension.[i]

Private C. Ross of Company H, 90th Pennsylvania Infantry was 19 years old when he was shot in the left arm on May 10, 1864. The top of the humerus bone was splintered, and when he arrived at Washington D.C.’s Douglas Hospital 4 days later, fever, failing strength and “suppuration” (infectious discharge) from the wound forced the doctors to operate. Assistant Surgeon W. Thomson decided to resect the humerus—removing the splintered top of the arm bone—and performed the operation “by a straight vertical incision” and “but little loss of blood.” Ross “soon recovered from the shock of the operation, and continued steadily to improve in health and strength.” By September 20th the wound had “entirely healed,” and from November 1864 until August 1865, he worked in the hospital kitchen. “He has a very useful arm, the motions and strength of the forearm, hand, and elbow joint being as good as the uninjured side. He can raise the hand to the mouth.” Ross left military service on August 21, 1865 and later received a military pension.[ii]

On May 10, 1864, Private Ephraim J. Tripp in Company B of the 77th New York Infantry got whacked on the head “with the butt of a musket which produced a severe contusion of the scalp and a simple fracture of the cranium.” The 42 year old survived the skull fracture and had “no very serious derangement.” Tripp returned to his regiment in October—unfortunately in time for the battle of Cedar Creek where he fell with a groin wound. He moved between hospitals in Martinsburg, West Virginia and Albany, New York, eventually discharged from service on August 7, 1865 “on account of loss of power in the lower extremities, and impairment of the mental faculties, resulting from the injury of the head.” The Spotsylvania injury seems to have had longer-term effects than initially considered, but Tripp lived through two hospital experiences.[v]

Some wounded Confederates made their way into the Union medical records. For example, Lieutenant J. P. Wilson of Company B in the 9th Virginia Regiment got a wound about two inches in length across the top of his skull on May 10, 1864. Two weeks later, Wilson entered a Confederate hospital in Farmville, Virginia and was eventually furloughed on July 1. Though he later spent more time hospitalized with intestinal illness, “the injury of the head gave no further trouble.”[vi]

Twenty-year-old Private Alvin Hubbard fought in Battery M of the 5th U.S. Artillery. His injuries from May 12, 1864, may be difficult to read about, but he did survive. Hubbard was wounded “by a solid shot or a large fragment of shell, which struck both knees, fracturing the patella and opening the joint of the right knee, and inflicting a large flesh wound on the inner side of the left knee.” Hubbard was carried to a field hospital belonging to the “Artillery Brigade, Sixth Corps” and two days later taken by wagon-ambulance to Fredericksburg. By May 24, he had arrived in Alexandria with “his constitutional condition…much disturbed, pulse quick and frequent, appetite poor.” And no wonder—his right knee and leg were “badly swollen, painful” and retaining fluid with an “unhealthy discharge from the wound” while his “left knee was black and swollen.” The following day (May 25) surgeons administered chloroform, amputated his right leg, and cut to repair his left knee since that joint was uninjured. Hubbard “rallied well from the operation and the after treatment consisted of stimulants, opiates, and nourishing diet.” He moved to several different hospitals in Alexandria and Washington D.C. before receiving a military discharge nearly a year later on May 19, 1865. Twelve years later, a doctor reported: “The stump of the amputated limb is sound. The wound on left knee healed, leaving a large scar, and the patella so dislocated upward that this leg can be only semi flexed.” Hubbard received a pension.[xi]

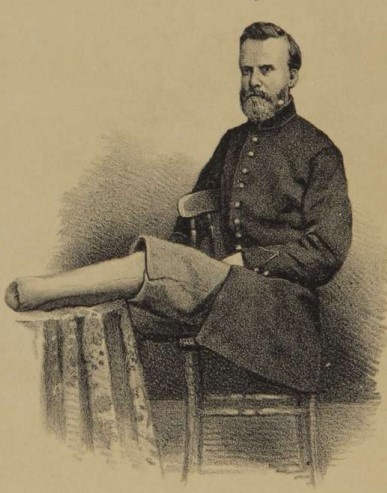

Whether he wanted to be included or not, Private A.K. Russell of Company H, 1st Massachusetts Heavy Artillery had his medical record fully recorded and his photograph included in the published volume. Russell was 43 years old when he was wounded on May 19, 1864. Shot in the left foot, the ball entered his heel and ploughed upward, crushing the metatarsal bones. Field hospital surgeons administered chloroform and performed a Syme’s operation that same day—basically amputating his foot at the ankle, but saving part of the uninjured heel pad. By the time Russell arrived at Emory Hospital, sutures had burst and signs of infection were present. Doctors and nurses fought the “unhealthy discharges”, using “linseed, charcoal, and yeast poultices” along with adhesive straps and cold water dressings. The prognosis did not look good since Russell was “much exhausted and suffering from loss of appetited, with derangement of the system generally.” However, by June 3, the medical team “thoroughly cleansed” the injury and added a padded splint to help the remaining limb heal properly. “By July 12th the patient was doing well and [the bone was healing]. About August 18th the stump had nearly closed and the patient’s general health was good. Two weeks afterwards he left for his home on furlough.” In August, Russell had a photograph taken of his injury. He was released form military service on June 2, 1865 and received a pension and a prosthetic. Unfortunately, Russell’s medical history doesn’t end there; sometime before January 1871, he had a second amputation, six inches below the knee. After the second operation, he seems to have recovered well, according to pension reports.[xii]

These men and these records represent the hundreds who did survive woundings at Spotsylvania. Not everyone died. I keep reminding myself of that this week. Even the total casualty numbers represent the dead, the wounded, and the missing. Yes, these soldiers were scarred by war, but they lived.

Spotsylvania battlefield was one of the places that I regularly went to find outer peace during 2020. I still do not understand how such once-deadly places can give a sense of relief now. Maybe they shake something within our souls; a knowledge that whatever fear, grief, or loneliness we think we face…it is not solely unique in the human existence. Perhaps at an old battlefield we feel that chain of human suffering and feel part of something bigger, something rather horrifying, and yet something with potential for stronger good. The ground holds the echoes of loss, courage, and endurance. Perhaps these hallowed fields can remind us that if some of them survived…then there is a way forward. Survival and scars is still a story with hope and life.

Sources:

Ancestry.com and Fold3.com archives were consulted for, census, enlistment, and pension papers.

[i] The medical and surgical history of the war of the rebellion (1861-65), Volume 2, Part 1, page 920.

[iI] Volume 2, Part 2, page 538.

[v] Volume 2, Part 1, page 45.

[vi] Volume 2, Part 1, page 105.

[xi] Volume 2, Part 3, page 273.

[xii] Volume 2, Part 3, page 596-597.

Here’s one – a Union soldier who survived his wound at Spotsy, as well as having been wounded at Gettysburg and Antietam, as described in that Victorian language pattern.

“George W. Maltby… at the age of seventeen he enlisted in Company H of the One Hundred and Eighth New York Volunteer Infantry, which history records as one of the most gallant commands in Hancock’s Army Corps. During his service Mr. Maltby participated … including Antietam, Gettysburg, and Spotsylvania Courthouse. He was wounded in all three of the battles mentioned, and at the last named was so injured as to be disabled for further service. He went to Satterlee Military Hospital at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania where he remained until he received his discharge in November, 1864…”

From “City of Buffalo Its Men and Institutions. 1908. Published by the Buffalo Evening News” page 137

Source: Google books https://books.google.com/books?id=S09KAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA158&lpg=PA158&dq=%22brady+%26+Maltby%22+Buffalo&source=bl&ots=yI8uIc3jHM&sig=ACfU3U0Nl7sSyQpi0P250AYOnGJA7m2u4Q&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjZ8Ie55e3-AhVDmGoFHXo2B7sQ6AF6BAgrEAM#v=onepage&q=%22brady%20%26%20Maltby%22%20Buffalo&f=false

Very thought-provoking, SKB. I appreciate your point: the big numbers of casualties @ Spotsylvania include long lasting disabilities that reminded the participants daily of the ferocity of fighting there.

Sarah Kay,

I was reading your last wonderfully thoughtful paragraph of this piece. Your words have echoed my feelings when I wondered why I find so much peace in a place where so much suffering and death occurred. I think your words in this article, in that paragraph, put a name to feelings that I thought couldn’t be right to feel in such a hallowed area. Thank you for expressing these thoughts to me and all the readers. I couldn’t help but validate my own feelings no matter what, but I am sure your words validate the feelings of others as they walk on these fields by what you’re shared in this paragraph. Thank you very much!

My great grandfather’s older brother was in the same battery M at Spotsylvania on May 12. 1864 as Alvin Hubbard. He too was badly wounded and sent to same places. He wasn’t so lucky. Discharged same time as Hubbard, but sent home to PA to die, Joseph Wilbur Stevens. His father, John Bowman Stevens was at Appomatoxs Court House and asked to be discharged after Lee surrendered to get home to PA before his son died. Army refused and he was discharged 3 weeks later. He got home 2 weeks after his son died. The father died in 1890 from disease contracted during the war.