The Second Assault on Port Hudson

For Nathaniel Banks, his defeat on May 27, 1863 at Port Hudson was the turning point of his life. A victory would have allowed Banks to proceed to Vicksburg and take command or at least share in the acclaim of the city’s fall. Now he was stuck besieging the secondary prize. To his wife Mary he wrote “I lay down my knife and fork at breakfast, I wake up at night and swear.” He was agitated, sleepless, and put on weight. Banks also spent time at the front inspecting the lines. In one instance while with the 8th New Hampshire, a sharpshooter nearly killed him.

Banks brought in more and heavier cannon, numbering 166 by June 13. Port Hudson was continually shelled. Entrenching tools were forwarded and the Federals built trenches and inched towards the Rebel lines. Over the weeks more regiments were called up. Banks expanded black recruitment, in no small part to make up for his losses. Banks also asked Grant for 8,000-10,000 men to supplement his ranks. Grant refused, and even turned the question back on Banks asking him for men. Lastly, Banks reorganized his forces from an unwieldy five divisions to four under William Dwight, Halbert Paine, Christopher Augur, and Cuvier Grover. Godfrey Weitzel held overall command of Paine and Grover’s divisions.

In the Rebel lines, powder was plentiful and food was not an issue at first. However, artillery ammunition was increasingly scarce, and even on May 27 the men used improvised canister, blasting the Federals with railroad spikes, broken pieces of metal, knives, and even nuts. Meanwhile, the men contended with rising temperatures and rain that turned newly dug trenches into quagmires.

Outside of the trenches of Port Hudson, John Logan’s Confederate cavalry did not do much at first. He spent the days organizing his command at Clinton while futilely searching for artillery ammunition. On May 29 Logan told Joseph Johnston a force 8,000 to 10,000 men could drive Banks out. Logan added that there was enough forage in the region sustain 10,000 men for thirty days of active campaigning. He restated the point on June 7, saying that without more men large stores in the area might fall. He also insinuated that if victorious at Port Hudson, a move might be attempted on New Orleans. Johnston did not act on Logan’s suggestions.

Banks decided Logan had to be defeated and he would use Benjamin Grierson’s cavalry. Grierson was in a bad mood and he preferred to be with Grant at Vicksburg. Grierson’s riders were an experienced and disciplined outfit who disliked their eastern counterparts. In one incident some of Grierson’s men disguised themselves as Confederates and captured a company of the 14th New York Cavalry, relieving them of their newly furnished weapons and saddles.

On June 3 Grierson, with 1,800 troopers, managed to approach Logan without being detected until they were one mile from Clinton. Logan’s advance guard ambushed Grierson along the Comite River. Logan, who was nearby playing poker, then rode out with the rest of his brigade. The forces skirmished for hours along Pretty Creek. The Federals withdrew due to Logan’s stout defense, the rough terrain, and low ammunition. Logan and his horsemen hotly pursued the Federals capturing most of Grierson’s wagons.

Banks was undeterred. He sent Paine with a column on June 5. They reached Clinton on June 7 and only managed to capture twenty sick Confederates. Paine likely lost more men than that from sunstroke. As for Clinton, it was looted and partially burned, with some men drinking a large cache of rum before torching it.

While Paine chased Logan, Banks planned another attack. According to captured men, Franklin Gardner’s garrison suffered from desertion and deprivation, although a few might have been plants since Gardner was confident he could repulse Banks if he struck again. David Farragut and Dwight took these stories at face value and Banks was won over. He began planning his attack on June 9 with Weitzel but the two argued, Weitzel claiming that Banks was “talking nonsense” while Banks stormed out saying he would “decide the matter himself.” On June 11 a series of probes were launched. These were done in a haphazard way and led to hundreds of losses, although two Rebel cannon were disabled. On June 12-13 Banks planned with Dwight, Weitzel, Paine, Grierson, Augur, and Grover. Banks accepted a plan put forth by Grover and Weitzel. Augur was to make a feint while Paine stormed the Priest Cap, a dominating height. Weitzel, directly overseeing Grover’s division, would hit Fort Desperate at dawn in conjunction with Paine. Dwight would also try to find a way along the river and gain the rear of “the Citadel,” a position on the extreme right of Gardner’s lines.

On June 13 at 11:45 a.m. a thunderous barrage commenced. Banks sent a letter to Gardner, complimenting his defense, but noting that it was hopeless to resist. Gardner laughed and merely replied “My duty requires me to defend this position, and therefore I decline to surrender.” Grover upon hearing of Gardner’s reply, said “Old Gardner was always as obstinate as a mule.” Weitzel said “Well, we all know what is to comes next.”

The June 14 attack was not to be a repeat of May 27. The ground was thoroughly scouted and precise attack orders were given. However, the Rebels were in an even stronger position and many men now had two muskets, one rifle for long range work and a smoothbore loaded with buck and ball for a close volley. The furious barrage and Banks’ surrender demand meant Gardner’s men were alert and ready. Also, Paine was not confidant. He told the chaplain of the 8th New Hampshire that “he wished no order would ever again be given for a Sunday fight.” Final preparations were a bit rushed and Paine had to hurry his men into position.

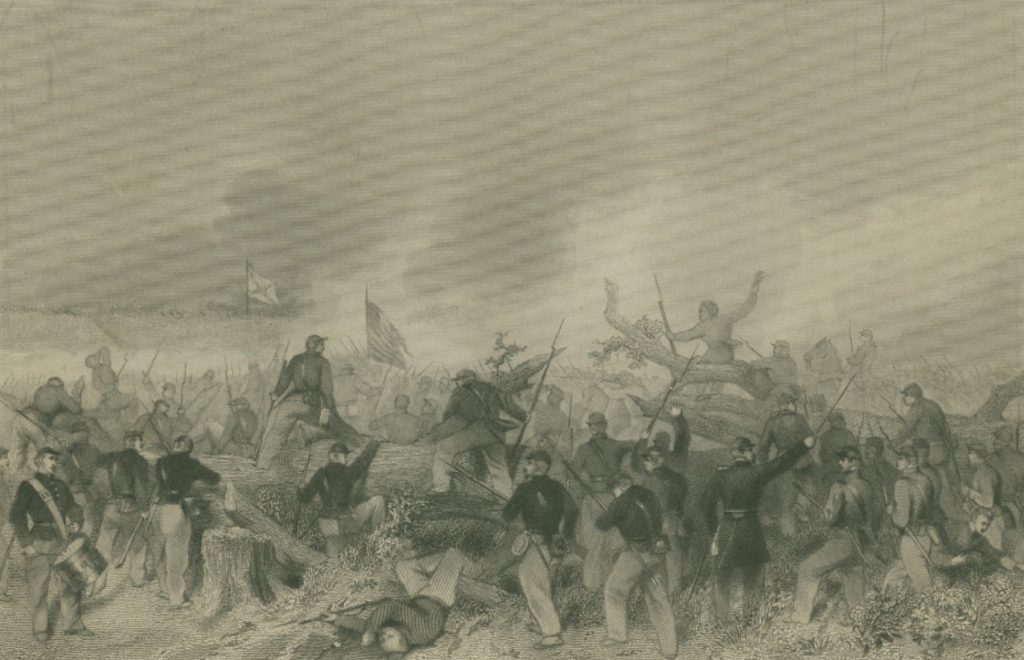

The barrage reached a crescendo around 3:00 a.m. Paine then aligned his men and they dashed into the fog and advanced within ninety yards of the Priest Cap. The Rebels were ready and his assault column was shredded. Paine heard a Rebel officer scream “Shoot that d––d long haired officer.” Soon after, Paine went down with a wound. In the shifting Confederate lines a hole opened and some men from the 4th Wisconsin, 8th New Hampshire, and 25th Connecticut breached the Priest Cap. However, with Paine down, there was no one to direct the reserves and the early morning fog added to the confusion. In the breach, the 1st Mississippi hurtled itself into the Union ranks. The fighting was savage, and the breech was contained although not erased. Meanwhile, Henry W. Birge took command of the division and threw two brigades in which were massacred.

Weitzel did not strike until 7:00 a.m. due to terrain and the failure of the 12th Connecticut to fill in a ditch. Even worse Weitzel was supposed to hit Fort Desperate, but the engineers confused it with the Priest Cap. The Federals were attacking one of the strongest positions in the line. However, the men did reach the lines, among them Color Sergeant Samuel Townsend, a Confederate deserter who joined the 91st New York in Pensacola. He planted the colors and was soon riddled with bullets, one of them apparently coming from his brother, a member of the 49th Alabama. He died six weeks later. Coming behind the 91st New York was Elisha B. Smith, leading Weitzel’s old brigade. The unit was shredded, and Smith went down with a mortal wound, extolling his men to press on. Weitzel by now was utterly convinced the assault was doomed, but Banks ordered him to storm Port Hudson no matter the cost. The attack would continue.

Next into the maelstrom was Richard Holcomb’s brigade. Holcomb was killed instantly, a bullet splattering his brains. Simon Jerrad of the 22nd Maine found himself in command. At 10:00 a.m. another attack force was gathered, but Jerrard had enough. He had earlier waved his sword and shouted “Come on my brave boys; follow me!” Now he declared before his regiment commanders “If General Banks wants to go in there, let him go in and be damned. I won’t slaughter my men that way.” Banks was determined and asked that a storming party of 200 volunteers be gathered, every man guaranteed a promotion. The group was formed, but Banks thankfully relented.

Augur’s sham attack was also a failure. The Rebels were hardly fooled and suffered few losses. At the Citadel, Dwight made his move. He originally wanted Grierson to force his way into Port Hudson by moving along the river’s edge. They would then nab Gardner and fight back to the lines. Grierson deemed it lunacy, while Dwight said “In spite of the reputation he has gained by his raid, that damned militia officer was afraid to execute my plan.” Dwight instead would rely on 150 horsemen from the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry. It was a bad plan, made worse by Dwight and his staff getting progressively drunk as the morning wore on. Dwight’s men were instantly pinned down and his attack produced even fewer results than Augur’s demonstration.

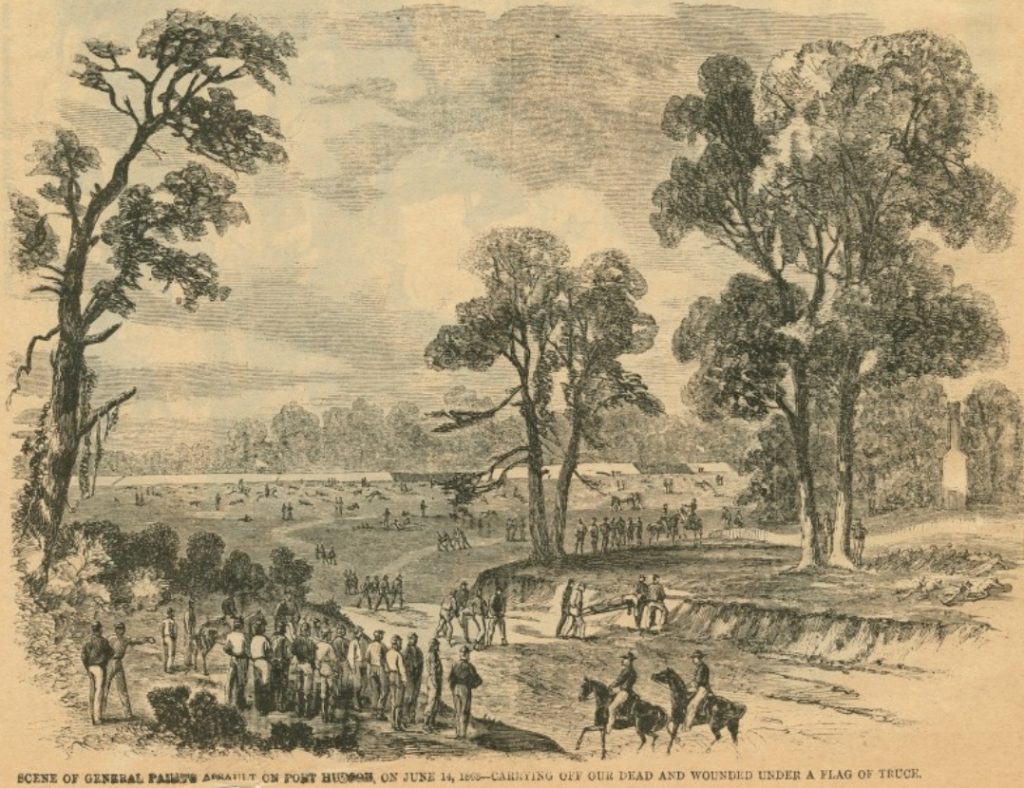

Most of the fighting on June 14 was confined to a relatively narrow area and Paine recalled it was “blue with the uniforms of our dead, wounded, and dying.” Losses on June 14 were nearly as bad as May 27’s official numbers, totaling 1,800. The 4th Wisconsin and 8th New Hampshire suffered around 60% losses.

Banks and Paine blamed the nine months regiments. Banks even had Jerrard “dishonorably dismissed” and the order of his dismissal read before the brigade. Jerrard’s men sided with him and did not witness his removal. For Banks, it was a personal low point and a useless act of pettiness, but it did show his will. In spite of the fiasco of June 14, Banks told his men “One more advance and they are ours!”