Lieutenant James W. Dixon: The Baby Before the Breakthrough

I recently found some unique biographical information on a Sixth Corps staff officer in the form of his mother’s journal from the first year of his life. With a twenty-month-old of my own at home right now, the entries certainly resonated more than they would have before… even if this was not quite what I expected to be adding to my file on the soldiers who fought at the Petersburg Breakthrough on April 2, 1865.

Connecticut Whig James Dixon served two terms in the U.S. House of Representatives from March 1845-1849, concurrent with the James K. Polk administration. Elizabeth Lord Cogswell Dixon joined her husband in Washington in late November 1845. Seven months pregnant at the time, she also brought her two daughters—Elizabeth (Bessie), age 4, and Clementine Louise (Clemmie), age 1. Regarded by a contemporary as “the most accomplished lady I have ever seen in Washington,” Elizabeth and her husband prominently entered Washington’s elite social circle.[1]

Elizabeth chronicled her experience in the national capital in a journal preserved by the Connecticut Historical Society in the Dixon Family Papers, 1843-1864, Ms. 76582. Caroline Welling Van Deusen, Elizabeth’s great-great-granddaughter via Clemmie, transcribed the document for the White House Historical Association’s publication in 2013, providing this unusual glimpse at the Civil War officer’s early life.

James Wyllys Dixon, Elizabeth’s “darling little son” was born at 9:30 a.m. on February 9, 1846. His father was an outspoken proponent of completely annexing Oregon, then held in joint occupation with Great Britain, and the House of Representatives debated that possibility on the day of his namesake’s birth. Elizabeth insisted that James attend to his congressional responsibilities, noting, “I felt quite well & so delighted at being the mother of a little boy.” Major General Winfield Scott, the commanding general of the United States Army, called on the house that day and was informed the family “had a new recruit for him.”[2]

The two young Dixon daughters were especially curious about the new addition to the family, who they all took to calling Bunty. When the baby boy was laid down to sleep in a large armchair “sweet Bessie would stand & lean over him with her sweet face and golden curls looking like a little angel.” Meanwhile, younger Clemmie “would come & cry to see this pretty live baby & was so delighted with it she could not be bribed out of the room.”[3]

Despite the good cheer Bunty brought to the house, the baby struggled to feed. “The efforts I made to nurse the baby nearly killed me as I was determined to try, while life permitted,” wrote Elizabeth. “It is such a comfort to a baby but as I had to have several persons to hold me to do it & was so faint after it Dr. Lindsley advised me to give it up, as many hours as possible 36 or more & so I lost a great part of the milk & Bunty took to his bottle which the untidy nurse was not particular to keep very nice & that made me very nervous but I consoled myself as best I could thinking how many poor children live with no mother & no care—& so grew Bunty & was vaccinated [ed., presumably for smallpox]—& went on finely.”[4]

The family returned to Connecticut for the summer and again all traveled to Washington that November. Ten-month-old James did not enjoy the train passage, as he “got frightened at the noise & shrieked like a steam whistle” until a nurse pacified him with candy. The scared baby gummed at the treat with an empty mouth, as a doctor visited the following month to investigate why he was yet to show any teeth. That Christmas he received “a swan to move in the water with a magnet.” The parade of visitors through the family’s Washington home spoiled the children with presents. For his sister Clemmie’s third birthday, on which Bunty surprised the family by making his way across the room on his own, Bunty also received a “whip with which he was much pleased and a gingerbread horse whose qualities he soon tested.”[5]

Others in their Washington circle recently had babies of their own and the families wanted to compare the children. This included Secretary of the Navy John Y. Mason’s wife Mary, who had born eleven children, and of whom Elizabeth joked, “they have almost masons enough to build a house.” The Prussian ambassador’s wife particularly wanted to converse with Elizabeth, because “she knew my baby was brought up on the bottle” and had been unable to do so with hers. Madame la Baronne de Gerolt praised the Dixon children as the most beautiful she had seen, Elizabeth noted, so “of course I thought her lovely.”[6]

The U.S. Congress was in session again on Bunty’s first birthday, so once more James Dixon had matters on which to attend. Elizabeth visited Capitol Hill that day and was invited into a side gallery to, for the first time, hear her husband address the House. Representative Dixon argued against allowing the extension of slavery into any territory gained from Mexico in the ongoing war between the two countries. “He celebrated thus Bunty’s birth day, and the speech was famous at home and praised by the papers as ‘one of the ablest & most eloquent’ of the session,” his proud wife wrote. Abraham Lincoln, just beginning his term as the representative for Illinois’s 7th District, later praised it as the best speech he heard on the matter.[7]

In that day’s journal entry, Elizabeth reflected on her one-year-old’s life and prophetically envisioned his future. “Tuesday was our dear Bunty’s birthday. James Wyllys Dixon, age 1, a stout, rosy noble little boy now at an age to be the least anxiety, as he cannot [illegible] into any mischief—. Who can tell his future? Oh, may he be spared to be useful and good and virtuous. I do not desire great fame for him unless he is eminently pious & virtuous and then I should love to have him serve his country with honor but if he can only inherit his dear father’s goodness will not that be enough?”[8]

James Dixon returned to Washington in March 1857 as a Senator. Having now also joined the new Republican Party, he campaigned in Connecticut for Lincoln’s election. In the wake of that victory in 1860, Dixon strongly pushed the new president to consider Gideon Welles for the Secretary of the Navy position in the cabinet, demonstrating the esteem in which Lincoln considered his opinion. Senator Dixon was reelected in 1863, thus serving through the entirety of the Civil War. Elizabeth meanwhile had struck up a friendship with Mary Todd Lincoln, with whom she ministered to the wounded soldiers recovering in Washington’s hospitals. Their oldest son found an important role to play in the war’s final months.[9]

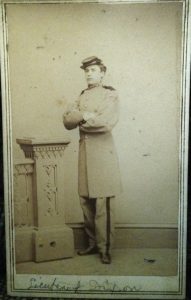

James Wyllys Dixon had attended New Haven’s Russell Military Academy and went by Jamie to distinguish himself from his father. In mid- January 1865, he received a commission as a first lieutenant in the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery and mustered into service on February 11. His anticipated unit served as infantry in Major General Horatio G. Wright’s Sixth Corps of the Army of the Potomac, but the veterans did not react fondly to the news. First Lieutenant Michael Kelly observed in his diary that many of the other commissioned officers and all the sergeants were “mad because Senator Dixon’s son has just joined this day as a Lt. to our Regt. They don’t call it right to put a stranger over them & indeed it is not.”[10]

However, Connecticut Governor William A. Buckingham made the appointment to secure the nineteen-year-old a spot as aide-de-camp on Wright’s staff. Wife Louisa Marcella (Bradford) Wright was a native of Culpeper, Virginia, but the general hailed from the Nutmeg State. The families became acquainted there and continued to call upon each other whenever their paths crossed.[11]

Young officers typically filled the role of aide-de-camp. They managed, delivered, and clarified communications and needed to maintain a full working knowledge of the organization in which they served, effectively bridging the gap between headquarters and the field during active operations. Dixon would have carried around the Army Officer’s Pocket Companion, which elaborated on his job:

“Aides-de-camp are attached to the person of the general, and receive orders only from him. Their functions are difficult and delicate. Often enjoying the full confidence of the general, they are employed in representing him, in writing orders, in carrying them in person if necessary, in communicating them verbally upon battlefields and fields of maneuver. It is important that aides-de-camp should know well the positions of troops, routes, posts, quarters of generals, composition of columns, and orders of corps; facility in the use of the pen should be joined with exactness of expression; upon fields of battle they watch the movements of the enemy; not only grand maneuvers but special tactics should be familiar to them. It is necessary that their knowledge by sufficiently comprehensive to understand the object and purpose of all orders, and also to judge, in the varying circumstances of a battle-field, whether it is not necessary to modify an order when carried in person, or if there be time to return for new instructions.”[12]

Dixon joined majors Arthur McClellan, Richard F. Halsted, Thomas L. Haydn, and Henry W. Farrar as aides-de-camp to assist Wright at the head of three divisions of eight brigades and forty-three regiments for a total around 14,000 men. Effective fulfilment of their assignment required far more than could be gleaned from a manual. Aides bore the responsibility of representing the general in his stead, including amending his orders on the fly given the ever-changing situation. Thus, the trust inherent in the position meant that generals frequently selected family or friends for the position. Nevertheless, the addition of a member to Wright’s staff from outside of the corps, particularly one who had not yet served in the army, rankled those who had coveted the assignment for themselves. Another Connecticut officer groused in his diary:

“General Wright must have a poor opinion of his corps, if he cannot by this time find timber in it good enough to make Aides de Camp of without going to Connecticut. There are plenty of men in this regiment yet uncommissioned, and yet unkilled, as respectable, as able, and probably as brave, as can be found anywhere,—and they deem it rather shabby treatment, after they have marched through fire and blood for months, after many of them have been perforated with rebel bullets, and are now on duty with scarcely healed wounds, for General Wright to fill a vacancy in the Second Connecticut by the ‘donation’ (that is what they call it) of a boy who has remained with his mother all through the war, until the fighting is all over, and the whole world knows that the rebellion is in the article of death. But then, you know, his father has been of enormous service to the country. Soldiers must take what they can get. They must put their heels together, keep their eyes to the front, and ask no questions.”[13]

With much to prove, Lieutenant Dixon joined Wright’s staff outside of Petersburg, Virginia in February 1865. The corps manned the stretch of Union earthworks south of the city, while the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia tenuously clung to both Petersburg and Richmond, their capital twenty miles to the north. Dixon rode along the Union lines conveying messages from corps headquarters. He took to the activity and grew just as familiar with the horses as their notable riders, recalling that Wright “was always well mounted, and his horses were invariably bays or dark browns.” Brigadier General Frank Wheaton, commanding one of Wright’s divisions, “rode a remarkable beautiful horse of dark copper color, almost black and handsomely dappled. This animal had luxuriant white and flowing mane and tail.” His first major combat responsibilities meanwhile came on March 25, when, after the Union Ninth Corps repulsed a Confederate offensive east of Petersburg, the Sixth Corps seized the enemy picket line immediately in their front.[14]

One final, bloody campaign remained for the Union forces to complete their victory. Grant incorporated elements of three different armies into his plan. On March 29, Major General Philip H. Sheridan’s mounted Army of the Shenandoah pushed for the Boydton Plank Road at Dinwiddie Court House and the South Side Railroad beyond to threaten the Confederate supply lines. Major General George G. Meade instructed the Army of the Potomac’s Fifth Corps (Major General Gouverneur K. Warren) and Second Corps (Major General Andrew A. Humphreys) to depart their entrenched Union camps and march west to support Sheridan. Three divisions from Major General Edward O.C. Ord’s Army of the James transferred from east of Richmond to fill the vacated lines to connect the mobile columns back to Wright’s static position.

The Sixth Corps and Major General John G. Parke’s Ninth Corps, southeast of Petersburg, had standing orders to assault the Confederate lines in their front should they detect any weakness. Whatever the strength that manned them, the fortifications remained an imposing obstacle. “No ordinary earthworks these; they had been for many months an impassable barrier to the Union forces,” recalled Lieutenant Dixon. “Erected scientifically by their troops under the supervision of competent engineers, they had been strengthened from time to time, as opportunity offered, until they were regarded by friend and foe alike as almost invulnerable.”[15]

At 4 p.m. on the campaign’s fourth day, April 1, Meade sent orders for the Sixth Corps to launch its fateful attack the following morning. As Wright prepared his men for the daunting assignment, Grant learned of Sheridan’s victory out at Five Forks and expanded Meade’s orders into an attack all along the lines as soon as the men could be put into position. Lieutenant Dixon had a busy evening as the orders kept changing to reflect the situation. Eventually the generals agreed to postpone each corps’ attack assault until 4 a.m. on April 2. In a war full of forlorn hopes, unsupported assaults (or piecemeal if so), and halfhearted charges, Wright’s final instructions to his eight brigades stand out as a premier example of how to decisively rupture the enemy’s fortified line. Dixon undoubtedly helped disseminate these orders to the corps.

One mile of open ground separated Wright’s main line from the Confederate entrenchments. The Sixth Corps pickets, because of the fighting on March 25, posted themselves in rifle pits halfway across the field, with their Confederate counterparts just a quarter mile in front of their own entrenchments. This provided Wright with ample space to position the forty-two regiments he committed to the attack into a giant wedge with Brigadier General Lewis A. Grant’s Vermonters centering the corps along Arthur’s Swamp. Two brigades formed in echelon to the left and another five formed in echelon to the right. Most had a regimental front, compacting the formation and providing the opportunity to hit the Confederate lines in waves.

Wright instructed each brigade commander to distribute axes to those in the lead to cut through the obstructions. The remainder relied mostly on the bayonet, as Wright cautioned against pausing to open fire in the assault. Artillery batteries stood ready to follow up each division’s attack, while twenty Rhode Island cannoneers accompanied the assault with their firing implements to use any captured pieces against the defenders. Many of Wright’s subordinates specifically briefed their commands on the task that awaited them, a preparatory measure not always taken before a battle. This extra step contributed to one of the most important conditions for a successful frontal attack—high confidence among the men who were making the assault. Above all, the Sixth Corps commander stressed the need for silence among the men while getting into position overnight and then awaiting the forward movement. “The fire of the enemy’s pickets was received by the solid columns in grim silence,” noted Dixon, who struggled to keep his horse calm under the barrage.[16]

Finally, at 4:40 a.m., a single cannon’s blast from Fort Fisher signaled the assault. Wright’s men rose and immediately swarmed past the Confederate pickets, who managed to frantically alert those back in the main line of the massive onslaught before them. The pioneers swiftly chopped at the obstructions while the most enterprising soldiers in the front ranks found paths used by the Confederate pickets to navigate through the obstacles. Within minutes, the lead companies bounded into the ditch fronting the main line of entrenchments and immediately clambered up the other side to engage the ten North Carolina and Georgia regiments targeted by Wright’s assault.

So long as the 14,000 Union infantrymen kept moving forward, the 2,800 defenders could not feasibly repulse them, and the battle plans—clearly impressed upon the men prior to the assault—had factored in many of the conditions that could stall their progress. Chaotic hand-to-hand struggles broke out along the wall as the Union soldiers threw themselves among the Confederate garrison, but each bayonet thrusted toward a bluecoat meant one less rifle firing into the next wave that followed. Wright’s men quickly subdued those Confederates who had not already broken for the rear. “The living wedge was driven home, wider and wider grew the gap, and soon the whole corps was in the works,” Dixon recalled.[17]

The staff officer remained active throughout the day as the Sixth Corps expanded their breach all the way to Hatcher’s Run before turning north toward Petersburg. That afternoon they settled into place with their left flank on the Appomattox River, blocking the direct Confederate route out of the city. Robert E. Lee’s army began circuitously pulling out of the defenses that night, entirely abandoning both Petersburg and Richmond. The Sixth Corps joined the pursuit westward and helped corner the Confederates at Appomattox seven days later. The decisiveness of their attack on April 2 forced Lee during that final week to abide by the Union timeline without real opportunities to escape and prolong the war. Wright acknowledged Dixon’s role in his official report following Lee’s surrender and recommended a promotion to captain.[18]

At that time, Elizabeth Dixon was still in the nation’s capital. She nervously awaited updates regarding her son in his first active campaign. She awoke at 11 p.m. on the night of April 14 to a carriage hurriedly pulling up to her house bearing a message from Captain Robert Lincoln. “I immediately thought he had come from the Army, and brought some bad news from Jamie,” she confided to her sister. Rather, she received summons to join the distraught First Lady at the Petersen house across from Ford’s Theater. Elizabeth consoled Mary Todd throughout the night and was present in the house until President Lincoln died. Her lieutenant son received permission to return to Washington to accompany the funeral procession in full uniform.[19]

James Wyllys Dixon continued his army career for five years, including additional service on Wright’s postwar staff. He settled in Flushing, New York, where he held various roles in municipal government, served prominently in veteran organizations, and wrote for newspapers and magazines. A New York contemporary claimed: “Few writers of his day wrote more prolifically or from so many interesting angles concerning news and sports, and none was better acquainted with the Civil War period in all its aspects.” He and wife Frances Stillwell Dixon had ten children of their own before his death on March 9, 1917.[20]

Endnotes:

[1] E.O. Jameson, The Cogswells in America, Boston, MA: Alfred Mudge & Son, 1884, 295.

[2] Elizabeth L.C. Dixon, diary, February 9, 1846, in “Journal Written During a Residence in Washington during the 29th Congress,” White House History, Volume 22, Summer 2013, 66-68.

[3] Dixon diary, February 9, 1846, 67.

[4] Dixon diary, February 9, 1846, 68.

[5] Dixon diary, December 5, 22, and 29, 1846, and January 16, 1847, 73-84.

[6] Dixon diary, January 1 and February 6, 1847, 81-93.

[7] Dixon diary, February 9, 1847, 97. Nelson R. Burr, “United States Senator James Dixon, 1814-1873: Episcopalian Anti-Slavery Statesman,” in Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church, Volume 50, Number 1, March 1981, 44. For the complete speech, see Speech of Mr. Dixon, of Connecticut, Against the Expansion of Slave Territory Delivered in the House of Representatives of the U.S., Feb. 9, 1847, Washington, DC: J. & G.S. Gideon, 1847.

[8] Dixon diary, February 9, 1847, 96.

[9] John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1973, 310. Commemorative Biographical Records of Hartford County, Connecticut, Chicago, IL: J.H. Beers & Co., 1901, 1. Burr, 57.

[10] Michael Kelly diary, February 2, 1865 in Michael Kelly Diary, MS 79237, Connecticut Historical Society.

[11] “City Intelligence,” Hartford Courant, August 4, 1865. “Sundries,” Hartford Courant, September 24, 1866.

[12] William P. Craighill, The Army Officer’s Pocket Companion; Principally Designed for Staff Offices in the Field, New York, NY: D. Van Nostrand, 1863, 51-52.

[13] Theodore F. Vaill, History of the Second Connecticut Volunteer Heavy Artillery, Winsted, CT: Winsted Printing Company, 1868, 140-141.

[14] James W. Dixon, “Some Army Horses,” Army and Navy Journal, June 3, 1911.

[15] James W. Dixon, “The Sixth Corps in the Appomattox Campaign,” Springfield Republican, September 13, 1886.

[16] Horatio G. Wright to George D. Ruggles, April 22, 1865, in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Volume 46, Part 1, 902. “Credit to Sixth Corps,” Connecticut Western News, October 3, 1912.

[17] “The Flushing Veterans,” Brooklyn Times, April 1, 1890.

[18] For more on the Petersburg Breakthrough, see A. Wilson Greene, The Final Battles of the Petersburg Campaign: Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion, Second Edition, Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee Press, 2008, and Edward S. Alexander, Dawn of Victory: Breakthrough at Petersburg, March 25-April 2, 1865, El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2015.

[19] Elizabeth L. Dixon to “My dear Louisa,” May 1, 1865, in “Lincoln’s Death: Eye-witness Account,” The Collector, Volume 63, Number 3, March 1950, 49-50.

[20] Henry Isham Hazelton, The Boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens, Counties of Nassau and Suffolk, Long Island, New York, 1609-1924, New York, NY: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1925, 293.

First of all, what a cute cat. I nominate the name “Inky” for the kitty. I vote the Dixon family photo’s caption say, “James Wyllys Dixon, wife Frances, and their ten children and cat, Inky” Is Caroline Welling Van Deusen a relative of Dixon?

Second of all, what a great description of the responsibilities of aide-de-camp! A great article with new-to-me info. Thank you ECW