Franklin Martindale, the Burning of Bedford, and the Lee Family, pt. 1

By the summer of 1864, war was not new to Shepherdstown, West Virginia. Situated along the Potomac River, it had played host countless times to Union and Confederate troops. The entire town served as a hospital for the Confederate army following the nearby battles of South Mountain and Antietam. But the town’s residents were about to experience something new entirely on July 19, 1864.

General David Hunter was in charge of Federal troops in the Shenandoah Valley. During his campaign a month earlier, Hunter’s men laid waste to the Confederacy’s breadbasket. Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, commanding all United States forces, instructed Hunter “to eat out Virginia clear and clean as far as they go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of this season will have to carry their provender with them.” The orders explicitly stated, “I do not mean that houses should be burned, but every particle of provisions and stock should be removed and the people notified to move out.” Hunter exceeded these orders and directed retaliatory measures against some of the state’s leading citizens.

Previously, in Lexington, forces under Hunter’s directive burned the Virginia Military Institute and the home of Virginia’s governor John Letcher. Confederate forces under Jubal Early struck back when in Maryland, destroying Postmaster General Montgomery Blair’s home. Now back in the Valley by mid-July, Hunter upped the ante again.

According to Hunter’s biographer, Edward A. Miller, the general “clearly believed that he was forced to operate among a hostile and aggressive population and that it was therefore necessary to show strong authority and no tolerance of any actions or opinions that might be termed anti-Union or pro-Confederate.” Hunter’s next act leaned anti-Confederate.

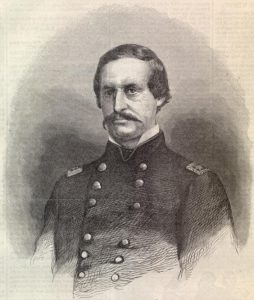

On July 17, Hunter issued Special Orders No. 128 from his headquarters in Harpers Ferry. It instructed Captain Franklin G. Martindale of the 1st New York (Lincoln) Cavalry to ride with 15 men to Charlestown “and burn the dwelling-house and outbuildings of Andrew Hunter, not permitting anything to be taken therefrom except the family.” Andrew Hunter was a distant cousin of Gen. Hunter’s and a Virginia senator. The orders then told Martindale to destroy Charles Faulkner’s home in Martinsburg. Hunter’s home burned to the ground that day, but Faulkner’s was ultimately left standing.

Two days later, Hunter ordered Martindale out again, this time to Shepherdstown. Martindale’s targets were two more homes, those of Alexander Boteler, a former Confederate congressman and staff officer, and Bedford, where Edmund Jennings Lee, a cousin of Robert E. Lee, resided.

Captain Martindale seemed an ideal fit for the task. While the men under Hunter’s command—and perhaps those under Martindale’s too—deplored this destruction “in the strongest terms,” Martindale was described as “a man who never shirked his duty, pleasant or disagreeable.”

Martindale and his fifteen men reached Fountain Rock, Boteler’s home, south of Shepherdstown, “just after dinner,” where they found Boteler’s daughters Tippe and Lizzie. Lizzie’s three children were also home when Martindale’s force reined up in front of the house. Dismounting, the captain handed the ladies a letter without saying a word. Addressed to Martindale from Hunter, the note stated, “You are ordered to proceed to the houses of A. R. Boteler and E. J. Lee and to burn everything under cover on both places with their contents.”

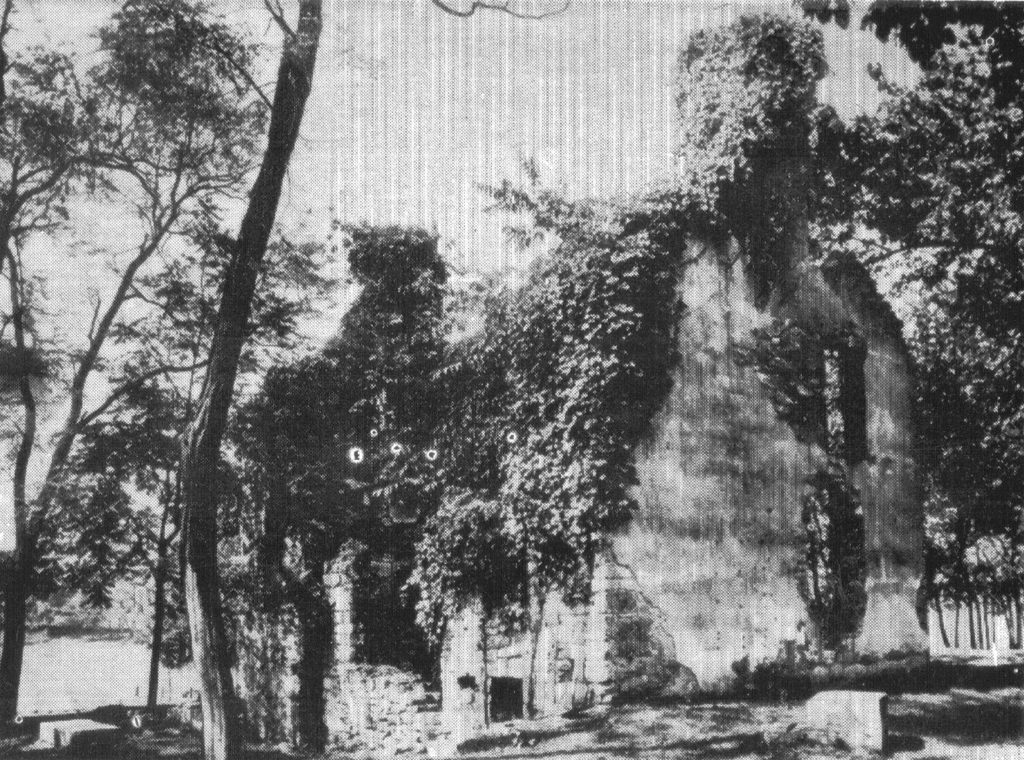

The Federals quickly began their work. “They piled up the furniture, and with camphene, &c., built the fire that has burned deep in our hearts.” It took 20 minutes for it to “have been dangerous to enter the house.” Tippe continued, “The barn, in which was stored all the hay, just cut, the servants’ house, the library, with the books, cabinet of minerals, valuable historical papers and documents—are all gone.” The only things spared from the flames were the smokehouse, dairy, springhouse, and five chairs.

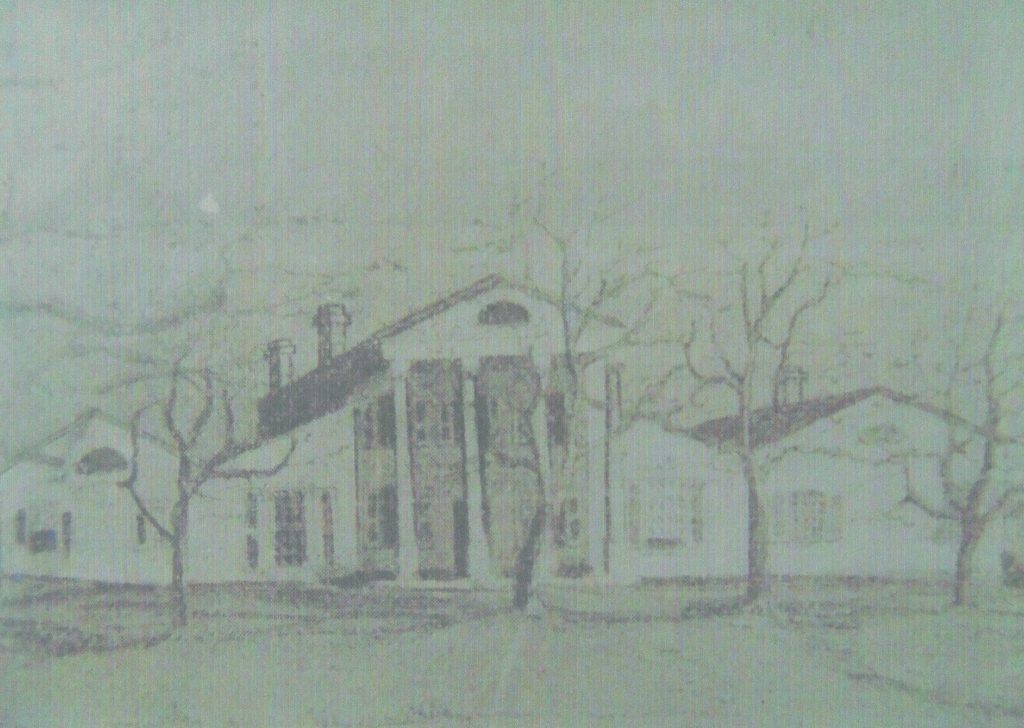

With one-half of their mission completed, Martindale’s column rode into Shepherdstown and then out the Duffields Road to Bedford, the Lee home. Bedford was described as “a large and handsome old colonial mansion, built of brick, with stuccoed walls. It had a splendid portico, supported by four large wooden pillars which were said to have been made from the masts of the famous revolutionary ship, the ‘Constitution.’”

At Bedford that night were Henrietta Bedinger Lee and two children, Netta and Harry, as well as the house servants, Peggy and Margaret. Edmund Jennings Lee II was gone from home. Henrietta had been unwell “for some days,” but well enough on July 19 to eat supper, which included some ice cream that Harry made.

Twenty-year-old Netta was in her room writing a letter when Peggy burst in and drew Netta’s attention to the burning Boteler home. “Dem Yankess is a comin’ right here down de pike, as sho’ as I’m bawn,” Netta remembered Peggy saying. Alarmed, Henrietta rose from her bed and vowed to go to Fountain Rock to help the women and children. She was stopped by the arrival of more locals with information that Bedford was the next target. Henrietta told the children and slaves to “save what you can, but first of all, do not forget your father’s command: ‘Should the house ever take fire, save my papers first.’”

Everyone sprang into action and secured the papers in the garden “far from the house.” They rushed back into the house to grab whatever else they could, then Martindale and his men arrived. Martindale entered the house and found a sickly yet defiant Henrietta standing at the door to her room.

“Madam, I have orders from General Hunter to burn this house and its contents and also every outbuilding,” said Martindale. Henrietta expressed surprise that Martindale would carry out “such a wicked order.” Martindale replied that he would. “You shall not burn the house which my father, a soldier of the Revolution, built. What did he, or I, ever do to you?” Martindale shot back, “Woman, you must be a fool, here are my orders; read them; I shall carry them out to the letter,” as he thrust the paper into her hands.

While this tense conversation transpired, Martindale saw slaves, children, and other locals attempting to remove items from the house. He “ordered them to put down the things they tried to remove, threatening to shoot them,” recalled Netta Lee. “We defy you to shoot us, we will not take orders from you,” said Netta.

But it was too late. Martindale’s soldiers were already piling furniture in the dining room, packed straw underneath the mound, poured coal oil all over it, and struck a match. Quickly, the flames spread. The civilians watched as one by one, the columns crumpled under the heat and the fire consumed the historic home.

Before departing, Martindale approached Mrs. Lee. “Madam, I have come to tell you that I have been obliged to carry out my orders in burning your home; I also wish to offer you my pity—” but she cut him off there.

“Stop sir, I command you!” she screamed. “You pity me? I scorn your pity! But listen to me! Do you see the one remaining column, about to fall? That, sir, is the last of the original masts of the Federal frigate Constitution, ‘Old Ironsides.’ My Father, a brave officer of the Revolution, built this home after that war. He went in as a boy, young and strong; he came out after serving seven years, weak and broken. He died at the early age of forty-five. Your grateful country has honored his memory by turning me, his daughter, and these, my children, upon the world, homeless and destitute. Now you may go, sir. You have done all the harm of which you are capable; I defy you to do more, and I utterly scorn your pity. Be gone out of my sight!”

Witnessing her mother’s tongue lashing of Martindale, Netta recorded, “The brave Captain quailed…as he turned and slunk off like a whipped dog.” It would not be the last lashing Martindale would receive from Henrietta Bedinger Lee.

Stay tuned for Part Two.

I TRULY ENJOY THE WAY STORY IS PRESENTED. PLEASE CONTINUE=I AWAIT NEXT STORY WITH GREAT ANTICIPATION.

Sherman’s “make Georgia howl” often pales in comparison. Hunter and Grant by association were very equally rotten.

I’m always somewhat surprised that many seem to be surprised by the brutality of war. Throughout human history, war, by definition, brings destruction, savagery, retaliation, lawlessness.

By historical standards, the American civil war was comparatively mild in it’s impact on civilians.

Sometimes war is necessary, sometimes it’s just an emotional response to hurt feelings, but it is always devastating for anyone involved. Total destruction of the civilian population has been the norm, not the exception, up until now.

Great articles…

As Americans, particularly white Americans, it’s interesting how in reviewing our Civil War, we sometimes recoil from the perceived barbarism of specific, targeted house destruction, or the destruction of the husbandry of farms, often those owned by apolitical individuals. We have no such qualms, in general, when evaluating the bombing of Germany or Japan. It was “necessary”.

Perhaps our delicacy lies with the fact that the Confederacy did not, ultimately, create an existential threat to the Union. They were geographically constricted by their economic underdevelopment. Also, slavery, however vile, was not the horror of the Holocaust nor as brutal as the Japanese military elite. And finally, as our half hearted resolution to Reconstruction demonstrated, white Northerners wanted to get on with their lives, and not do the heavy load lifting we did post 1945.

However, we sometimes forget that this was, at least on the battlefields particularly from 1864 onward, a brutal Civil War. The soldiers, north and south, were having the veneer of civilization removed. Northern soldiers just had more opportunities to engage in retaliatory warfare. There are those observers, then and now, who rejoice in the destruction, often with non rational, emotive statements like “well, they deserved it.” The ultimate tragedy is that the memories of the war, particularly among white southern women, concerned the devastation left behind. As one historian has said, the northerners went home and created the future, the white south tried to recreate a past that never existed. We still live with that legacy today.

I have Pryor ancestry who were on the Confederate side, and while I deplore that they may have owned slaves, I have wished I knew their story, what their lives were like before and after they lost their home and moved westward in poverty. Wonder if we might descend from some of the same lines?