The Killer Angels Revisited – Part I

As the 30th anniversary of the movie Gettysburg fades away with 2023, the new year welcomes another important anniversary in the cultural annals of Gettysburg lore. This year marks the 50th anniversary of The Killer Angels, which remains the seminal work of historical fiction on the battle of Gettysburg. And it’s no wonder. Author Michael Shaara’s imagery and prose offer a vivid narrative of the three-day battle.

Published at the end of the Vietnam War, Shaara revisits a more noble, military age by delivering an epic novel of the greatest battle fought on American soil. The book follows the experiences of revered Confederate General Robert E. Lee; his pragmatic and cynical second-in-command General James Longstreet; sometime professor and colonel of the 20th Maine Regiment, Joshua Chamberlain; as well as the seasoned cavalryman, General John Buford.

While The Killer Angels bestows its audience with a vivid (and mostly accurate) account of the battle, Shaara’s true genius lies in his veiled commentary on the meaning of the war. Slavery therefore plays a prominent role in the ruminations and dialogue of the characters.

Shaara offers different, and often diverging, perspectives on the institution, particularly from the Confederate point of view. In one chapter, Confederate General James Kemper insists that the South is fighting for its “freedom from the rule of what is to us a foreign government.” The other Confederate officers agree “what a shame it was that so many people seemed to think it was slavery that brought on the war, when all it was really was a question of the Constitution.”[1]

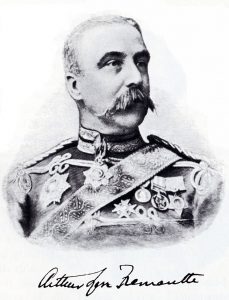

Some critics of the novel argue that it perpetuates the Lost Cause myth that the war was not about slavery. However, in Shaara’s view, the Confederate reluctance to admit slavery as the cause of the war began during the war, and he uses Longstreet to acknowledge this. Unlike his comrades, Longstreet does not ascribe to the delusion that the war is about a question of states’ rights or the Constitution. “The war was about slavery, all right,” he ruminates. “That was not why [he] fought but that was what the war was about.”[2] Shaara’s other foil to the Confederate cause is Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Freemantle, a British observer who is accurately depicted as a Southern fanboy. Freemantle acknowledges slavery as an “embarrassing” stain on an otherwise noble record of the Confederacy.[3]

Shaara contrasts the Confederate viewpoints with those of his Northern characters. When members of the 20th Maine Regiment stumble across a runaway slave, former sergeant Buster Kilrain mutters, “And this is what it’s all about.”[4] Tom, Colonel Chamberlain’s brother, is perplexed when a Confederate prisoner insists that he is fighting for his “rights” and not slavery. “We asked them why they were fighting this war,” Tom recounts the story to his brother, “thinkin’ slavery and all, and one fella said they was fightin’ for their ‘rats’”.[5]

Chamberlain’s inner conflict about the meaning of the war also represents the country’s divisiveness at large. As he approaches the runaway slave, Chamberlain experiences a “flutter of unmistakable revulsion” of which he is ashamed.[6] Later on, he wonders how much the slave knew of the war, of borders and states, and Dred Scott. “And yet he was truly what it was all about,” Chamberlain muses.[7] The experience calls to mind Chamberlain’s confliction. On the one hand, he mechanically recognizes the “divine spark” equal and alive in every man. However, Chamberlain is also troubled by his own “crawly hesitation” in approaching the runaway slave.[8] In this way, Chamberlain’s inner conflict is that of the nation, representing the diverging viewpoints of North and South.

Shaara expands the meaning of the war through his commentary on the Southern aristocracy. While the North is progressive and forward-thinking, Shaara argues the South is stuck adhering to old aristocratic ideals, of which slavery is a symptom. He depicts Virginia generals like Lee, JEB Stuart, and George Pickett as chivalric. While Lee and his men approach the battle on the first day, Shaara describes them “moving toward adventure as rode the plumed knights of old.”[9] Freemantle also notes the similarities between the Southern and European aristocracy before the battle on July 2: “Here they have that same love of the land and of tradition, of the right form [….] But the point is they do it all exactly as we do in Europe. And the North does not. That’s what war is really about. The North has those huge bloody cities and a thousand religions, and the only aristocracy is the aristocracy of wealth. The Northerner doesn’t give a damn for tradition, or breeding, or the Old Country. He hates the Old Country. Odd. You very rarely hear a Southerner refer to “the Old Country.” In that pained way a German does. Or an Italian. Well, of course, the South is the Old Country. They haven’t left Europe. They’ve merely transplanted it. And that’s what this war is about.”[10]

This passage calls to mind a series of key divisions between North and South, which resulted in nineteenth century sectionalism. Freemantle references the North’s ethnic diversity as a nation of immigrants, contrasting it the South’s old, English blood. But by invoking the North’s desire to upend the remnants of the European aristocracy, Shaara suggests that the Civil War represents America’s last step in its separation from Great Britain and the Old World.

In tangent to this cadre of old-fashioned, Virginia officers stands Longstreet, who dismisses the Southern aristocratic view of war as outdated and foolish. Instead, Longstreet advocates a new, pragmatic formula of defensive warfare, according to Shaara.[11] This is contrary to the long-accepted, Napoleonic method of an army meeting its enemy out in the open to do battle. It also contradicts the Victorian ideals of bravery and honor that Lee and the other aristocratic officers embody.

While Shaara perhaps exaggerates Longstreet’s reputation as a groundbreaking, defensive tactician, his separation of the general’s thinking from that of his Southern comrades is noteworthy. In this way, Longstreet’s character illustrates a shift brought about by the Civil War as the last old war, led by Lee and his knightly officers, and the first modern war, led by Longstreet’s innovative tactics. Shaara further delineates Longstreet from the old aristocracy of the South by referring to him as a man of Dutch, not English, descent.[12] This is just one of a series of parallels Shaara draws between Great Britain and the South, both representing the traditions of the Old World. After speaking with Fremantle about tactics, Longstreet admits to himself that “like all Englishmen, and most Southerners, Fremantle would rather lose the war than his dignity.”[13]

On the other side of the battlefield, Shaara portrays Chamberlain as an embodiment of the patriotic and progressive ideals of the North. He writes: “The fact of slavery upon this incredibly beautiful new clean earth was appalling, but more even than that was the horror of old Europe, the curse of nobility, which the South was transplanting to new soil. They were forming a new aristocracy, a new breed of glittering men, and Chamberlain had come to crush it.”[14]

An academic by trade, Chamberlain does not hail from the English ruling class left over from before the Revolution; he is the descendent of French Huguenot immigrants who fled the persecution of Europe. In fact, Chamberlain “had grown up believing in America and the individual and it was a stronger faith than his faith in God.” [15] Chamberlain’s stake in the Civil War as a means of breaking the aristocracy marks the war as a final break from the ways of the Old World.

Through the characters of Longstreet, Fremantle, and Chamberlain, Shaara shows that the meaning of the Civil War is complex and messy. The war is the result of the South’s unwillingness to abolish slavery but also its unwillingness to break free of the Old World. The war is a clash of the progressive and industrialized North with the antiquated and agrarian South. But Shaara also illustrates that the Civil War exists within all of us, as it does in the character of Chamberlain who struggles to make sense of the conflict himself.

To be continued…

[1] Michael Shaara, The Killer Angels, (New York: Random House, 1974), 65-66.

[2] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 244.

[3] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 156.

[4] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 179.

[5] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 180.

[6] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 179.

[7] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 181.

[8] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 179, 186-187.

[9] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 60.

[10] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 156.

[11] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 141-142.

[12] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 174.

[13] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 142.

[14] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 179, 29-30.

[15] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 29.

Excellent article. Looking forward to next installment

I would be interested to know if Michael Shaara was a student of the civil war and Gettysburg in particular. How did he become familiar with chamberlain , Fremantle, the 20th Maine , little round top etc? I remember visiting Gettysburg as a child long before killer angels and just being so confused by cemetery ridge and seminary ridge, devils den, the wheat field and the peach orchard, little round top and big round top . It took years of reading and the movie to get it all straight in my mind.

There are some good interviews with Jeff Shaara out there in which he talks about his father becoming interested in Gettysburg after taking a family trip to the battlefield. I believe he says, “My father knew a good story when he saw one. And he saw one here [at Gettysburg].”

As I am sure you can attest, that first trip to Gettysburg in quite impactful. I’ll never forget it at age 10. And to this day I continue to explore the many battlefields. Your analysis and reviews always inspire me to continue my Civil War journey.

This is wholly a misreading of ‘The Killer Angels’ and, by proxy, what the war was about, Longstreet, and the modern, progressive invented view of the war.

First, the novel is not mostly accurate, but mostly inaccurate. It relies hugely on Longstreet’s memoir, which has been debunked by anyone who closely reads the facts at hand – though this is not accepted by those who favor a revisionist view of the war and want to extoll Longstreet over Lee. One of the smaller errors, though one that has evolved into accepted belief somehow, is “the Confederate artillery always fires high.” I’ve read 1,500 books, memoirs, diaries and collections of letters from both sides of the Civil War. In not one of them does any historian or combatant, North or South, ever state any such thing. Where Shaara got this myth is anyone’s guess. But the real aim of the book is to say, “See? Just look at these arrogant Southern sons of bitches who deserve a thrashing from the noble, freedom and equality-loving DEI warriors of the North.” The review does the same, stating “While the North is progressive and forward-thinking, Shaara argues the South is stuck adhering to old aristocratic ideals, of which slavery is a symptom.”

If the North was so progressive and forward-thinking, why did six slave-holding States remain in the Union? Why did the Federal Government not immediately outlaw slavery in these States? Why did the North have in place for decades before the war the “Black Codes,” which severely restricted the freedom of resident blacks? Never heard of the Black Codes? Of course you have; when they were adopted in the South following the war, they were renamed “Jim Crow.” Why did slavery not end in the North until December 8, 1865? As for the “Lost Cause” and the issues of the war, it is modern dishonest revisionist that the South’s view of the war began only after the war began, and was furthered after the war. Entirely untrue. All one needs to do is look at the facts: The “Tariff of Abominations” of 1828. The Nullification Crisis of 1828-1832. The list is lengthy, and does not need to be included here, but the fact is that the South was contemplating secession for at least 30 years before it occurred, that numerous debates and crises occurred over its view that the Federal Government, intended to be small and limited by the Constitution, was growing dangerously large and powerful and quashing States’ Rights, which were supposed to be protected by the Constitution. Revisionists will deny these arguments existed because they don’t want them to exist; they want the Civil War to be simple, easy, and noble: “The Good Guys beat the Bad Guys and freed the Slaves! Don’t bring in complex and contradictory facts that make me read a lot and confuse me!” But their argument is ludicrous; after all, there was even a man named “States Rights.” A South Carolinian born in 1831 and served as a politician and officer in the Confederate Army. He was living proof that “The Lost Cause” was not invented during and after the war.

As historian Robert Ellis wrote: “By creating a national government with the authority to act directly upon individuals, by denying to the state many of the prerogatives that they formerly had, and by leaving open to the central government the possibility of claiming for itself many powers not explicitly assigned to it, the Constitution and Bill of Rights as finally ratified substantially increased the strength of the central government at the expense of the states.”

But if you want a deeper, closer explanation of the causes of the war, one that is balanced – though it does not hide bitterness – and correctly assigns blame to both sides, Southern diarist Mary Chesnut wrote this in real time – discussed in Southern society before and after the war began, and written down shortly after it began: “The war was undertaken to shake off the yoke of foreign invaders. So we consider our cause righteous. The Yankees, since the war began, have discovered it is to free the slaves they are fighting – so their cause is noble. They also expect to make the war pay. The Yankees do not undertake anything that does not pay. They think we belong to them. We have been good milk cows. Milked by the tariff, or skimmed. We let them have all of our hard earnings. We bore the bane of slavery. They got the money. Cotton pays everybody who handles it, sells it, manufactures it, &c &c – rarely pays the men who make it. Secondhand, they received the wages of slavery. They grew rich, we grew poor. Receiver is as bad as the thief. That applies to us, too – we received these savages they stole from Africa and brought to us in their slave ships. Like the Egyptians, if they let us go, it must be across a red sea of blood.”

Modern progressives and revisionists don’t want to admit it, because it futzes with their arrogance and sanctimoniousness, but what Chesnut wrote is the true perspective of Southerners – and honest Northerners agreed. Besides, let us not forget that only 1/125 Americans owned slaves, only 7/100 in the 11 States that seceded owned slaves, only 4/100 in the Confederate armies owned slaves and that, while slavery was protected in each of those States’ Constitutions once they joined the Confederacy – popularly used by progressives to insist that slavery was the sole cause of the war – slavery was also protected by one other Constitution in North America: the Constitution of the United States of America. And that Constitution, by the way, did not outlaw slavery until eight months after it had ended in the South.

Last – though the examples could fill a thousand pages – was the negative response in the Federal armies to the Emancipation Proclamation. In large numbers, officers resigned their commissions, soldiers deserted or refused to re-enlist when their terms were finished. Historian James M. McPherson admits in his book ‘For Cause & Comrades’ that he, too, initially thought the war was about slavery, but that reading thousands of Civil War soldiers’ letters for the book largely changed his mind. Without doubt, the overwhelming view of Northerners and Southerners, soldiers and civilians, was NOT that the war was about slavery. But to accept this truth is too much for revisionists and progressives to handle. They want the war to be simple, easy, and moral – that way, there is an All Good side and an All Bad side. With such, they can pronounce judgement, use the judgement to condemn half of American society and label them “racists” and “White Supremacists” – ignoring, by the way, as did Michale Shaara, that blacks and Native Americans also owned slaves – and then use the Civil War to promote their 21st Century ideology. In a word, it is dishonest.

But, Michael Shaara ignores all these contradictions. No pun intended, his novel is “black and white,” and as such is, along with the military errors, omissions and biases, a simple one, not a complex or great one – and certainly not an accurate novel of the Civil War. It is an enjoyable read, especially for youth – I liked it when I read it at 10 or 11 – but it is inaccurate in its portrayals of many of its characters (this also includes the fact that Chamberlain’s speech to the 2nd Maine mutineers took place in February 1863, not just before the Battle of Gettysburg), is unbalanced in that it takes the discredited Longstreet view of Lee and Gettysburg, and simplistic as well as dishonest in its assertions of the Northern and Southern perspectives on the war.

Wow! How do you find the time to troll the internet with all that reading??

Well Dan, I read books – not the Internet. Apparently, you do not. So that puts me 1,500 Civil War books ahead of you.

Holy States Rights Gist Batman! Not slavery; more the ramifications of slavery. In 1820 Thomas Jefferson saw it all coming with the Missouri Compromise: “we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go,” quoting a famous line from the Roman playwright Terence: “Auribus teneo lupum.”

I don’t really know how to respond to this assessment. I read this book decades ago. It’s a good book, in that it is entertaining. It’s also a novel. Novels are generally fictions. They might be rooted in historical events involving historical figures but they are still fictions. Mr. Sharra took significant ‘artistic license’ to ‘flesh out’ characters and the like. While he received many accolades for his portrayals of various battle scenes and locations and characters, he’s also received criticism for some of them (Chamberlain’s character and actions on Little Round Top are among those). I’m not here to comment about anything positive or negative about what was written, I just want to emphasize that referencing a novel for insight on a subject as complex as the American Civil War should be done with the proverbial grain of salt in mind!

Not sure if this the fact, but it does describe the theory of shooting high by two examples:

For rifles the projectile drops as the distance to the target increases. For artillery, the guide and historian at the Battle of Franklin battlefield stated three ways cannons were used, one being basically a lit shrapnel filled bomb that exploded over the on coming enemy regiments.

It was/is a great novel with a strong historical basis, but still fiction. But a great book

The book does present such a simplistic view of the causes of the war, that it is hard to read now. But, I suppose it appeals to folks with a certain self-righteous view of the war.

Tom