The Killer Angels Revisited – Part II

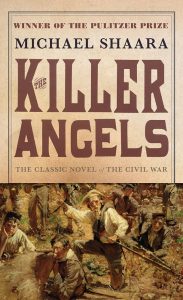

Part II of this series revisited some themes from the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Killer Angels in honor of its 50th anniversary this year. While author Michael Shaara offers a realistic and gripping account of the battle of Gettysburg, a deeper analysis of the book reveals his understanding of the Civil War’s layered and complicated meaning through the eyes of characters like James Longstreet, Arthur Fremantle, Robert E. Lee, and Joshua Chamberlain. While men like Lee embody the old traditions of the South (slavery and aristocracy), characters like Chamberlain represent the progressive and diverse North. In this way, Shaara sees the Civil War not just as a battle over slavery but as a clash between old and new.

Shaara also weaves the theme of reconciliation into his narrative. He sets the stakes of the battle (and ultimately the war) in a conversation between Chamberlain and his comrade Buster Kilrain. Chamberlain hypothesizes that if the Union loses the war, “there’ll be two countries, like France and Germany in Europe, and the border will be armed. Then there’ll be a third country in the West, and that one will be the balance of power.”[1] John Buford similarly wonders about what will happen if the North loses the war. “Could you ever travel South again? Probably not for a while,” he muses.[2]

Again, Shaara contrasts the United States with the Old World by comparing its fate with the warring nations of Europe. He argues that America, as a unified republic, hangs in the balance at Gettysburg. The Civil War will decide whether it will reunite as one country or crumble into belligerent factions, whether it will stand separately from the Old World or repeat the bloody history of Europe. In this way, Shaara presents the Civil War as a sort of second Revolutionary War, in which America must finally break away from the tenets of its European heritage. Slavery and the Southern aristocracy are America’s last ties to the Old World. Likewise, the Founders’ vision of America as a continental nation hangs in the balance as well. A Union victory would affirm this vision of a unified nation, but a Southern victory would not.

After the battle concludes, and the North emerges victorious, Chamberlain looks out across the carnage of the battlefield. He feels “an extraordinary admiration” for his enemy, “as if they were his own men who had come up the hill and he had been with them as they came, and he had made it across the stone wall to victory, but they had died.”[3] This reflection foreshadows the reconciliation of the two sides at the end of the war. By admiring his enemy “as if they were his own men,” Chamberlain recognizes that both the Union and Confederate armies are Americans.

If General Robert E. Lee represents the aristocratic past, Chamberlain symbolizes the reconciled future of the nation. The colonel notes to himself that he has “always felt at home everywhere, even in Virginia where they hate me. […] They give it all names, but I’m at home everywhere.” [4] Chamberlain’s reflection foreshadows the unity of the country after the Civil War, as he feels home even in the “enemy territory.” It also illustrates a dying devotion to statehood, embodied by Lee’s allegiance to Virginia. Chamberlain does not consider himself a Mainer; he considers himself an American.

Similarly, Chamberlain’s acknowledgement that the dead are “all equal now” also epitomizes the nation’s own recognition of equality and struggle to justify the war’s cost. This statement invokes the reconciliatory rhetoric of the post-war era, marked by images of veterans—from both North and South—shaking hands and embracing one another as fellow citizens.

The Killer Angels presents Chamberlain as a manifestation of America’s destiny. He acknowledges the sins of slavery (by fighting to absolve them) and looks to a more progressive and inclusive future. On the other hand, Lee represents the old aristocratic traditions and strict social hierarchy of Europe. Shaara depicts the general as a broken and tired commander after Pickett’s Charge.[5] Thus, Lee is a “dying breed” in a rapidly modernizing country.

Despite Shaara’s masterful and metaphorical writing, the truth of what happened at Gettysburg is probably different than seen through the eyes of his literary creations: the magnanimous Lee, the knightly Chamberlain—both of which probably thought different thoughts, felt different emotions, and lived different lives than portrayed in the novel. But The Killer Angels is a work of historical fiction and should be viewed as such. Much like its counterpart in cinema, the true power of the novel probably lies in its ability to garner public interest in the Civil War and affirm what the war’s participants thought it was really about. Despite some recent criticism to the contrary, The Killer Angels illustrates that slavery was at the heart of the Civil War.[6] But Shaara shows that slavery was also one irrevocable piece of larger tension between a diverse, industrial North and a traditional, agrarian South. The book characterizes the Civil War as a final test to see whether Americans are like their European forebearers and if democracy can survive to benefit all people.

Even 50 years after its publication, the novel continues to captivate new audiences. Just last month, I spoke with a first-time visitor to Gettysburg who told about a “new book” he read called The Killer Angels, which taught him more about the battle than any history class he took or documentary he watched.

Like many, I watched the movie Gettysburg before reading Shaara’s book, but both works remain a strong part of why I love history. I remember reading The Killer Angels and feeling like I was there, experiencing the battle alongside the characters. And I think the true power of the book is not how many minute details it gets right or wrong, but its ability to evoke a feeling in its readers and show what the war was truly about.

[1] Shaara, The Killer Angels, (New York: Random House, 1974), 189.

[2] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 48.

[3] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 365.

[4] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 127.

[5] Shaara, The Killer Angels, 359.

[6] Jeff Sherry, “Book Review-The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara,” Hagan History Center, June 12, 2020, (accessed January 3, 2024), https://www.eriehistory.org/blog/book-review-the-killer-angels-by-michael-shaara.

I read “The Killer Angels” many years ago, but the major impression I had was that it was only concerned with the commanders. Thousands of casualties are basically ignored while the author focuses only on the generals, what they are thinking, and how they are experiencing the battle. While that angle is important, I prefer the Civil War novels “The Red Badge of Courage” and Shelby Foote’s “Shiloh” any day–books that tell the story from the ground up, not the top down story of the elite.

The appeal of “Killer Angels” is the humanity of the historical figures. They struggle with poor health, exhaustion, family tragedy, resentments and rivalries with the folks on their own side. Sharra tells the story tightly focused on one point of view at a time. Mostly Longstreet and Chamberlain, but also Lee, Buford and Lewis Armistad. It humanizes them, and makes them accessible to a contemporary audience.

The professionals we spend time with, Longstreet and Buford, reject glory and the cult of honor, in favor of pragmatic and efficient war making, which is also the attitude of the modern reader.

Thank you for this insightful and interesting analysis of Killer Angles’ “back story” pertaining to the differences between North and South

The Killer Angels is a wonderful book, masterfully written and emotionally powerful, plus a lot of fun. However, I have a few problems with it, mainly the characterization and glorification of Longstreet. It also has some seemingly nationalistic views, like the Confederacy must be defeated because its too English (per Fremantle). But I think its virtues outway everything else. I do much more prefer Gore Vidal’s Lincoln.

An insightful post. Frankly, in the realm of Civil War historical fiction I rank Ralph Peters’ books far above this one and Shaara Jr.’s books. To follow up on Douglas Miller’s point, Peters portrays commanders but he also does a solid job of looking at the war from the “grunt’s” perspective. And among other things Peters – unlike the Shaaras – knows that Victorians didn’t speak in the non-profane, flowery way that they wrote.

Peters’s book is very good, as well. Definitely much more grittier and provides another perspective by highlighting the actions of Meade, Freeman McGilvery, and others.

Peters’s is much more real, but both books have their virtues.