Our National Cemeteries: Contrasting National and Local Cemeteries at Camp Parapet in Greater New Orleans

In commemoration of Memorial Day 2024, Emerging Civil War has been exploring national cemeteries. We must not forget, however, that many Civil War veterans, and veterans of our nation’s other conflicts, are not buried at national cemeteries. These veterans were instead laid to rest often in local cemeteries. In keeping with the theme of spotlighting cemeteries, I wanted to take a moment and explore one such cemetery with deep ties to the Civil War that likewise houses veterans: the Camp Parapet Cemetery in Metairie, Louisiana.

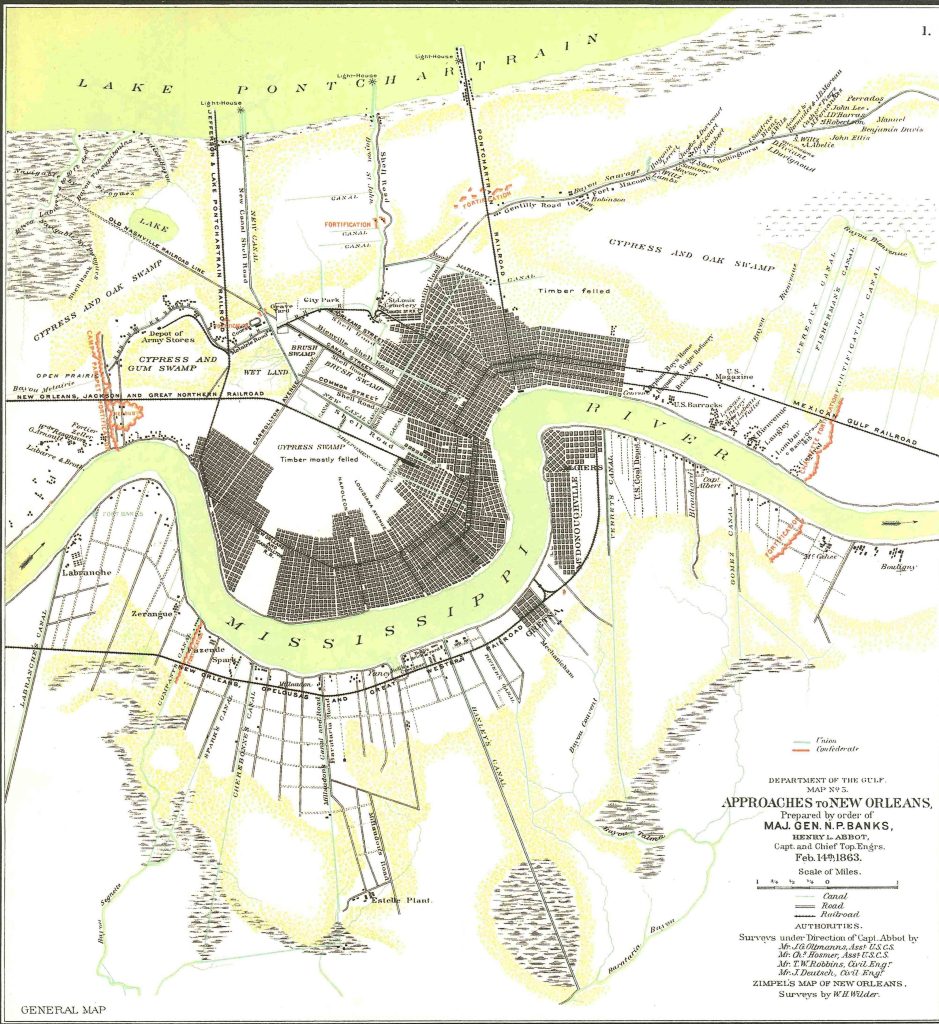

Fortifications related to Civil War New Orleans are mostly associated with the major defensive positions of forts Jackson and St. Philip covering the downriver approaches to the city. There were a host of others however, including coastal fortifications and lines of defense just outside the Crescent City’s outskirts. One of these, Camp Parapet, guarded the river and land approaches to New Orleans from upriver. Recently, I had the chance to visit the old cemetery that began as a burying ground for soldiers who died at the camp.

Camp Parapet was initially a Confederate bastion that went by the name Fort John Morgan. When the Crescent City was evacuated by the Confederacy in early 1862 however, the position was abandoned. Guarding the upriver approaches to New Orleans from where a Confederate counterstrike most likely would appear, United States forces immediately manned and strengthened the position, renaming it Camp Parapet and arming it with approximately twenty-four 24-pounder cannon.[1]

The fortifications are aligned with present-day Causeway Boulevard in Metairie, Louisiana. They began at the Mississippi River’s mouth and moved north. A large power magazine held the line’s explosives and cannon and entrenchments continued north past Metairie Road, stretching for over a mile. Today, two signs denote where Camp Parapet stood, one at the Mississippi River and another on the corner of Causeway Boulevard and Jefferson Highway. The camp’s powder magazine remains, but is difficult to visit and only sparingly open to the public.

Camp Parapet quickly became a refuge for enslaved people who self-liberated themselves as the war continued. It housed “several large contraband camps” that grew after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed.[2] Men in these camps were often “employed in the construction and repair of roads, fortifications and the line of railway” in the New Orleans area.[3]

Soldiers from New England, the Midwest, and New York, as well as locally recruited units such as the Louisiana Native Guards and First Louisiana Engineers, were assigned to the position throughout the war.[4] In his postwar memoir, soldier George C. Harding recalled landing at Camp Parapet and first observing “what I had often heard of but never expected to see – an entire regiment of slaves, regularly organized and drilled.”[5] Historian James G. Hollandsworth has noted that Camp Parapet was where “Brigadier General John W. Phelps had started everything” regarding African American wartime military enlistment by asking Maj. Gen.l Benjamin Butler “for weapons to arm fugitive slaves” in July 1862.[6]

As the war ground on, the inevitable occurred as people at Camp Parapet died. Though there was never any active combat at the camp, diseases and other problems took their toll, both among the soldiers assigned to the fortification and among those formerly enslaved who worked nearby. On the camp’s northern end, “near the Jackson Railroad track, ground was so unhealthy it was nicknamed ‘Camp Death.’”[7] By the end of the war, thousands of people were interred at the camp’s cemetery, which was established just west of the camp and just south of the railroad line.

Civil War veterans buried at Camp Parapet were reinterred at the Chalmette National Cemetery after it was established in the years immediately following the war just east of New Orleans, at the site of Andrew Jackson’s famed 1815 victory against the British. The Camp Parapet Cemetery lived on, however. Those who died there during the war who were not veterans remained, and it quickly became a cemetery for locals. It remains so today, serving as the burying grounds for the nearby Ross Church and First Zion Church.

Most of the attention regarding Camp Parapet is focused on its location as a U.S. military encampment and location where enslaved men joined the army. Very little, if anything, has been written documenting the cemetery. Thus, in a recent trip to New Orleans, I had some time and wanted to visit the cemetery, which is now sometimes called the Shrewsbury Cemetery and sometimes called the Fist Zion Cemetery. It is relatively small, and though it remains an active cemetery with burials from recent years there, the grounds are largely unkempt. Several headstones are laying loose with debris dotting markers and plots. There is not even a sign marking the location, though a few large oak trees provide some shade. The wartime railroad tracks remain just north of the cemetery.

Though veterans of the Civil War are no longer present, I found other connections among those buried there. Several graves marked the resting point for people born during the war, and the cemetery contains a host of military veterans from the Spanish-American War, World War One, World War Two, and the Korean War. I estimated that between 10 and 20 percent of those interred there are military veterans.

Among the veterans now buried at the cemetery were members of the 9th Regiment of U.S. Volunteers from the Spanish-American War. This was a segregated military unit of African American soldiers largely recruited from the New Orleans area and sent to fight in Cuba.[8] Perhaps it is most fitting that soldiers from this organization rest where their fathers and grandfathers from the Civil War may very well have also been initially laid to rest.

There are millions of veterans from the United States Civil War, and even though many are concentrated into our national military cemeteries, we cannot forget those who are buried elsewhere, or those who were temporarily buried elsewhere. Even the smallest cemeteries off the beaten path house hosts of veterans from the Civil War and beyond, and their resting places are worthy of acknowledgement and dignity in keeping with the magnitude of their sacrifices.

Endnotes

[1] Codman Parkerson, New Orleans: America’s Most Fortified City, (New Orleans, LA: The Quest, 1990), 90-91.

[2] Charles P. Bosson, History of the Forty-Second Regiment Infantry; Massachusetts Volunteers, 1862, 1863, 1864, (Boston: Mills, Knight, & Co, 1886), 335.

[3] Samuel C. Hyde, Jr. ed. A Wisconsin Yankee in Confederate Bayou Country: The Civil War Reminiscences of a Union General, (Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press 2009), 119-120.

[4] Hyde, A Wisconsin Yankee in Confederate Bayou Country, 119; Bosson, History of the Forty-Second Regiment Infantry; Massachusetts Volunteers, 1862, 1863, 1864, 219-220, 242, 332, 350.

[5] George C. Harding, The Miscellaneous Writings of George C. Harding, (Indianapolis, IN: Carlon & Hollenbeck, 1882), 309-310.

[6] James G. Hollandsworth, Jr. The Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience During the Civil War, (Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, 1995), 102.

[7] Bosson, History of the Forty-Second Regiment Infantry; Massachusetts Volunteers, 1862, 1863, 1864, 332.

[8] W. Hilary Coston, The Spanish-American War Volunteer: Ninth United States Volunteer Infantry Roster and Muster Biographies, Cuban Sketches, (Middletown, PA: W. Hilary Coston, 1899).

As a young boy in the 1950’s, I often rode my bike past Camp PArapet powder magazine before it was repaired and recognized as an historic site. I never knew about the cemetery. Is it near Causeway Bild and the railroad tracks?

It is , where you thought, I too , living on the river side of Deckbar Ave. road my bike in the area, it was a great place to grow up.