Our National Cemeteries: Chalmette National Cemetery and Nashville National Cemetery

When asked to write a blog post on national cemeteries, I had to jump at it. I have been doing cemetery tours in New Orleans for years. Locals generally do not shun such places either. Cemeteries are as dear to the city’s traditions as Mardi Gras and food. So I have visited many.

When asked to write a blog post on national cemeteries, I had to jump at it. I have been doing cemetery tours in New Orleans for years. Locals generally do not shun such places either. Cemeteries are as dear to the city’s traditions as Mardi Gras and food. So I have visited many.

My first thought was about how many national cemeteries I have visited in obscure places, such as Mill Springs and Popular Grove. When I visited Port Hudson in 2022, I was the only person there, besides my brother Daniel. The sun that April day was shining, and the sky had large white cumulus clouds: an ideal day for many people. The cemetery was immaculate, and yet it felt lonely all the same, much like the nearby Camp Moore Cemetery. Shiloh is also in an area few travel, but it is on a major battlefield so it gets more than the Port Hudson battlefield. Port Hudson’s battlefield park is maintained by Louisiana, not thoroughly advertised, and its rugged terrain makes it ideal for nature hikes as much as Civil War buffs and historians. I think the former outnumber the later among visitors.

I also thought of Chalmette National Cemetery. It is perhaps the oddest one of all. Chalmette National Cemetery sits on a battlefield, but not a Civil War engagement, but instead Andrew Jackson’s 1815 victory over the British. On the cemetery grounds, Edward Pakenham’s British regiments formed up and were then slaughtered in thirty minutes. Pakenham died heroically trying to press his men home. One can leave the cemetery and directly enter the battlefield park. Of those buried, only four fought in the War of 1812 and only one under Jackson. The site is little known even in the New Orleans area. In my visits, I am usually alone, save my brother.

Chalmette National Cemetery has only a little over 15,000 graves, mostly Union soldiers who died during occupation duty. It was a burial ground before its establishment in 1864, and the bodies of Confederates and freedmen were moved off the grounds after 1864. The freedmen cemetery was adjacent, but became overgrown and was abandoned soon after the war, but now has a historical marker. As to the Confederates, they ended up in Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2. It was a potter’s field like nearby Holt Cemetery, but it was abandoned in the 1920s and today Canal Blvd runs over it, between Greenwood Cemetery (resting place of generals Young Marshall Moody, Thomas M. Scott, and William Benton, the later the only Union general buried in New Orleans) and two old school New Orleans restaurants that recently moved there: Morning Call and Bud’s Broiler. This cemetery is gone and unlike St. Peter’s (a cemetery that was once in the French Quarter) wholly forgotten.

Chalmette National Cemetery was almost my sole choice. After all, I have been there many times. Its history is fascinating. It is unusual. It is in my hometown. Yet, I went with Nashville National Cemetery as well. I never knew of it until I wrote They Came Only to Die. I falsely believed an ancestor was at the battle on the Union side, and it drew me into the topic. Furthermore, I did have a Confederate ancestor in the campaign, but not the battle, serving under Nathan Bedford Forrest.

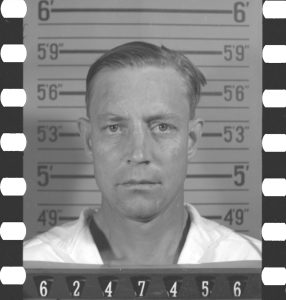

It would turn out I had a more direct familial connection to Nashville National Cemetery. My grandfather was James Leonard Chick. He was from Fayetteville, Tennessee, and his ancestor Samuel Chick fought in the 44th Tennessee at Shiloh and Perryville before deserting on the eve of Stones River. The family scattered in the Great Depression, one of James’s brothers dying in Pennsylvania in mysterious circumstances. James Leonard would be twice-married. His second wife was Alice, my grandmother, a fourth-generation product of the Irish diaspora to New Orleans and other cities. My father, William Joseph, knew little of his father. James Leonard fought in World War II as a member of the 11th U.S. Naval Construction Battalion (the unit’s tale was told in a personal history, Southern Cross Duty: 1942-1944). He fell ill in the Admiralty Islands, returned to San Francisco, and after disciplinary problems, was honorably discharged.

Facts about James Leonard become murky. My father knew little and was a man who would try to make relatives look better with half-truths. It seems though James Leonard suffered a terrible accident at the Half Moon Bar and ditched his family. Unlike my dad, I have no problem being blunt about relatives, and considering Alice’s temperament and cooking, I am not wholly unsympathetic to his decision. I confirmed he died in 1967 and found his grave in 2019.

It was not just that connection that drew me to Nashville National Cemetery as my favorite. It is expansive and in a quiet part of Nashville. That this huge cemetery is in a major American city makes it unusual. It is filled with Federals who died of disease while garrisoning the Confederacy and those who died in battle, particularly Franklin and Nashville. And there are two of the most beautiful cemetery statues I have ever seen.

In 1913, the Minnesota commissioned John K. Daniels to design five statues. The battle of Nashville was important to Minnesota. The 5th, 7th, 9th, and 10th Minnesota fought in the battle and distinguished themselves. I do not think any other battle had as many men from that state. The Minnesota state house contains a 1906 Howard Pyle painting featuring Minnesota regiments in the attack that broke John Bell Hood’s lines. Lucius F Hubbard led a brigade and became governor in 1881. Not until 1921 was the statue erected.

In 2006 another statue was erected to honor U.S. Colored Troops (USCT), of whom 1,910 are buried in the cemetery. The 12th, 13th, 14th, 16th, 17th, 18th, 44th, and 100th USCT fought in the battle. Most had never been in a fight, and it was a grisly baptism of fire. Many died in Nashville in two doomed attacks. The 13th USCT lost 40 percent of its number and five standard bearers in an attack on December 16. It impressed even some Confederates. James Thadeus Holtzclaw, who was wounded at Shiloh, Chickamauga, and Franklin wrote in his brigade report: “Placing a negro brigade in front they gallantly dashed up to the abatis, forty feet in front, and were killed by hundreds. Pressed on by their white brethren in the rear they continued to come up in masses to the abatis, but they came only to die. I have seen most of the battle-fields of the West, but never saw dead men thicker than in front of my two right regiments…”

Nashville National Cemetery is almost as unusual as Chalmette National Cemetery. It is in a major American city. Those buried are from garrison work, or they fought in battles less famous than Gettysburg and Vicksburg. While light on monuments, the two it has are impressive. It will never be as famous as Arlington and Gettysburg. But every cemetery means something to somebody, even if they do not know it. I wrote a book about the battle of Nashville and a grandfather I never knew is buried there, one of many descended from Confederate soldiers who fought for America after 1865. I am in that way more linked to Nashville than I am to Chalmette.

1 Response to Our National Cemeteries: Chalmette National Cemetery and Nashville National Cemetery