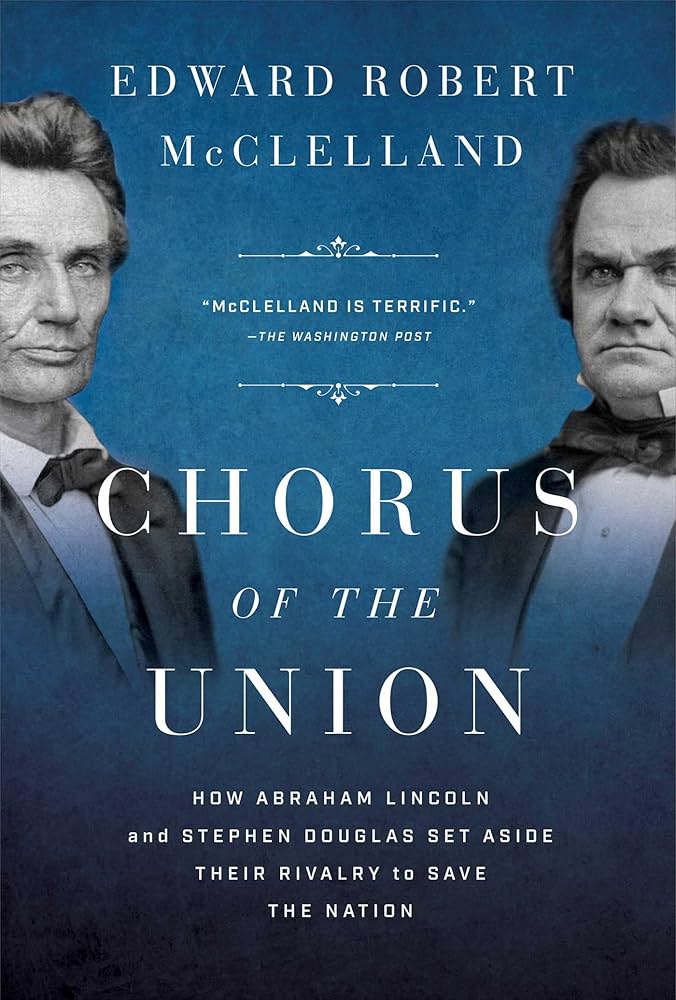

Book Review: Chorus of the Union: How Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas Set Aside Their Rivalry to Save the Nation

Chorus of the Union: How Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas Set Aside Their Rivalry to Save the Nation. By Edward Robert McClelland. New York: Pegasus Books, Ltd. Hardcover, 344 pp. $32.00.

Chorus of the Union: How Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas Set Aside Their Rivalry to Save the Nation. By Edward Robert McClelland. New York: Pegasus Books, Ltd. Hardcover, 344 pp. $32.00.

Reviewed by John B. Sinclair

Chorus of the Union: How Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas Set Aside Their Rivalry to Save the Union by Edward McClelland is roughly divided into four sections. The first examines the famous 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates for the Senate. The second part covers the 1860 presidential primary and general elections. The author then reviews the tumultuous events between Lincoln’s election and the firing on Fort Sumter. The final pages summarize Stephen Douglas’ efforts after Fort Sumter to dissuade secessionists from leaving the Union.

Any author of a new book involving Abraham Lincoln as one of the central figures bears a heavy burden. There are untold numbers of books on Lincoln, including books on his debates and relationship with Stephen Douglas. How then does this book stand apart from the crowd? Curiously, the author does not provide a preface or introduction to explain his intentions with this study. The front cover and dust jacket flap reflect a focus on an alleged “alliance” between Lincoln and Douglas to save the Union. The dust jacket flap also asserts that Douglas stopped campaigning for himself before the 1860 election and tried to convince Southerners to accept a Lincoln presidency. True? Not exactly.

Chorus of the Union begins with an immediate jump into the 1858 Illinois Senate debates (when Senate seats were decided by a state legislative vote and not a popular vote), with occasional “flashbacks” to earlier events. These debates are well-tilled ground for Lincoln scholars and others. Though there are no new striking revelations, the author does pen a workmanlike and creditable account. Douglas and Lincoln had divergent views on slavery. Lincoln was morally opposed to slavery (though he believed the Constitution permitted it in the states) and resisted allowing slavery to extend into new territories. Douglas, due to his first marriage, directly profited from slavery; pursuant to his belief in “popular sovereignty,” he argued that people in new territories should decide whether to allow slavery. Douglas criticized Lincoln for allegedly promoting Black equality and advocating civil war between the North and South. The debates drew enormous and enthusiastic crowds.

Though Lincoln lost the legislative vote for Senate, his political profile rose sharply after these debates, and he was eventually nominated as the Republican candidate for President in 1860. Douglas became the Democratic candidate after raucous conventions.

While Lincoln followed past practice of not campaigning for himself for the presidency, Douglas felt compelled to do so because of Lincoln’s popularity. Though late in the campaign, Douglas realized his chances of winning were diminishing, he never withdrew nor did he stop campaigning for himself. Referring to Lincoln, Douglas stated, “No man on earth would regret his election more than I would” and that Lincoln would be head of a party “subversive of the Constitution.” (227) Still, he attempted to reassure audiences that an elected Lincoln would be foiled by Democratic majorities in Congress. Again, the author provides a traditional account here.

Southern secession sentiment grew after the election. The book aptly describes Douglas’ legislative efforts in the Senate to stop secession through compromise proposals, which ultimately failed to achieve a consensus. In early April 1861, Douglas opposed the resupply of Fort Sumter and told his Senate colleagues that had he won the election the Union would not be facing this crisis.

The firing on Fort Sumter on April 12 changed much. Douglas met with Lincoln on April 14 and pledged support for the Union. He also recommended additional troops be raised and proposed strategic points to be defended. The author in one sentence states that Douglas was involved in “several more strategy sessions” with Lincoln and Winfield Scott, but unfortunately provides no details. (297) Douglas later issued what might be called a press release expressing support for Lincoln in defending the Union while being “unalterably opposed to the administration on all its political issues.” (298)

Between April 25-May 1, 1861, Stephen Douglas gave several impassioned speeches in Illinois, Ohio, and to a joint session of Congress in favor of preserving the Union. During this brief period, Douglas rose to what may have been his finest hour in public service. Sadly, he was already ill on May 1 and never reappeared in public before dying on June 3.

The final few pages dealing with Douglas’ post-Sumter efforts read more like a coda to his life than a premise for the book. Using the phrase “alliance with Lincoln” to describe his efforts seems a bit forced. Douglas was more a fellow traveler with thousands of Americans on the road seeking to preserve the Union.

The footnotes reflect quite a number of older sources with few references to newer scholarship on Lincoln. For those not familiar with the Lincoln-Douglas debates or 1860 election, however, Chorus of the Union is a fine place to start.

John B. Sinclair is a retired charitable foundation president and a retired attorney. He is a member of the Baltimore Civil War Roundtable, a member of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (James A. Garfield Camp No. 1), and a Life Member of the Lincoln Forum.

Good review. The Lincoln-Douglas relationship is an excellent subject to explore in our divisive times and with a divisive presidential election in full swing.

What the reviewer misses is that Douglas was the only true active presidential campaigner in the 1860 election. He, unlike Lincoln, realized that the fire eaters were in deadly earnest. He went south into the lion’s den to confront the secessionists, whereas the others campaigned through surrogates. He finished the campaign, I believe, in Mobile. To refer to Douglas as a fellow traveler is a travesty. As the Democratic chieftain, particularly in the upper Midwest, he was invaluable in cementing Unionist support for Lincoln’s initial war actions.

Mr. Pryor: The stated premise of the book is that Lincoln and Douglas formed an “alliance” and “worked together” to stop secession. It is in the context of that premise that I made the “fellow traveler” statement. Certainly, Douglas worked to allay Southern concerns of a Lincoln presidency as indicated in my review and continued his legislative compromise efforts up to the morning of Lincoln’s inauguration. I noted his laudable Midwest speeches to preserve the Union. Nevertheless, the evidence is at best scant to claim that Lincoln and Douglas had an “alliance” and “worked together.” So, I stand by my comment. I hope you read the book and let me know if you disagree.