Fourteenth Amendment Day: Horace Flack, Champion of This Famous Reconstruction Amendment, Seems to have Evolved in His Views of the Civil War and Its Aftermath

On this day in 1868, Secretary of State William Henry Seward issued a proclamation declaring the Fourteenth Amendment ratified and ordering it to be published as law. The meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment has been in dispute from that day to this.

A key part of this debate is whether that amendment requires the states to obey the Bill of Rights (a doctrine known as incorporation). In 1908, the U. S. Supreme Court said mostly “no,” but by 2024 the court had turned around to saying mostly “yes.” An important development in 1908 was the publication of a book called The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, which became a weapon in the Supreme Court argument over incorporation as well as the foundation of subsequent scholarship on both sides.[i]

The author of the book was Horace Flack. This article is not a biography of Flack, but a reference for certain aspects of his early life which relate to the subject of his book.

Looking at Flack’s early career, we see him speaking against a community (albeit abroad) which seceded in support of slavery. But he also spoke of the Civil War and its aftermath in Southern-establishment terms, hinting that a robust interpretation of the Reconstruction-era Fourteenth Amendment would have been anathema to him. As a scholar of the Spanish-American War, rejecting the concept of humanitarian intervention, he gave examples of cruelty in the Union war effort. But none of this stopped him from advancing the thesis of his Fourteenth Amendment book.

Flack was raised in rural Rutherford County and sent by his father to Wake Forest. He was a member of the Euzelian Literary Society, one of two literary societies dominating student life at Wake Forest (the other society was the Philomathesian).[ii] On February 16, 1900, the anniversary of the literary societies, those societies, based on their practice at the time, held a debate with four debaters – a member of each society defending and opposing the proposition under consideration. The debate topic on that day was “Resolved, that England was not justifiable in making war upon the Boers.” Flack was the Euzelian Society member who defended the negative. In other words, Flack defended the British against the Boers in the then-raging Boer War.[iii]

The Boers were a group of white farmers who wanted to establish their own republics in South Africa, resisting the British who wanted the Boers to be part of their empire. The interesting part of Flack’s speech is the beginning, where Flack noted how the Boers were part of the British Empire in southern Africa in the first half of the 19th century – until the 1830s, when the British abolished slavery in their colonies, and the Boers moved away from the British to establish independent Boer republics. It was these republics which the British would successfully reconquer in the Boer War of 1899-1901. The Boer “trek” of 1834, out of the domains of the British flag, created their republics, and would become part of the Boer national mythology.

Flack denounced the trek because it was motivated by the desire to preserve slavery. “The Boers lived in peace under British control from 1814 to 1834 when England freed the slaves in all the colonies. She paid the Boers about one half the value of their slaves, but they did not like this and so ‘trekked,’ not for love of liberty and for hatred of oppression, but for the license of the task-master and of the slave-driver. They wanted to get from under English control in order to capture and enslave more of the natives.” Parallels would have occurred to the audience.

Since the rules of debate sometimes assign people sides, rather than giving them full play to express their private beliefs, I’m curious how much of his own views Flack was expressing in his speech.

Later in 1900, Horace Flack’s uncle back in Rutherford County, a farmer, fought with one of his Black farmworkers and died. Local whites lynched the farmworker without getting punished.[iv]

Did this affect Flack’s attitudes? On the evening of February 15, 1901, as part of the literary societies’ anniversary proceedings, Flack gave an oration on “The Old North State Forever,” later republished in The Wake Forest Student. Here Flack gave what, for the next several decades, would be the orthodox position on the Civil War and its aftermath in North Carolina, as promoted by the state establishment. Cliché after cliché poured from Flack’s lips in the section of the speech given to the Civil War and what happened after that.[v]

Flack’s version in a nutshell: North Carolina had supported states’ rights and compromise of the sectional dispute, but when “forced” after Fort Sumter “either to aid in the subjugation of her Southern sisters or cast her lot with them,” she joined the Confederacy. The state’s Confederate soldiers made disproportionate sacrifices, and “every fifth bullet which went to swell the Union casualties came from a North Carolina musket.” General Lee supposedly said: “God bless North Carolina! she is first and last in every charge.” “Never indeed,” said Flack, “have any Anglo-Saxons displayed higher qualities than the ‘tar-heels’ on every battlefield.”

“[T]he people of North Carolina bore themselves with unparalleled heroism,” including “ the patient and uncomplaining endurance of want and suffering by our fair womanhood.”

After the defeat, Flack went on, North Carolinians heroically endured the physical devastation of the war’s aftermath, as well as the supposed political horrors of reconstruction: “Into hands still trembling from the blow that broke their shackles was thrust the ballot. Carpet-baggers filled our offices and robbed our treasuries, corruption was everywhere, life and property insecure, death rampant, and darkness brooded over the land…” Flack even referred to “the shameful and dishorable legislation of ’68,” though I’m not sure if this means state or federal Reconstruction measures (or both). But 1868 was the year in which the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted.

After Reconstruction was overthrown, Flack went on, Democratic leaders like Zebulon Vance were able to pass needed reforms. “But there has ever been one great barrier to the investment of capital from other States, and that barrier has been the negro question. It were better for society to be dissolved into its original elements – better for the tide of colonial vassalage to sweep again over our extensive country from seacoast to mountain peak, than for our liberties and institutions to be imperiled by an inferior race. This foul blot on the fair escutcheon of our State has been wiped off forever….the white man has again resumed his sovereignty.”

After Wake Forest, Flack went to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, where he studied political science under Professor Westel Woodbury Willoughby, who in effect was the political science department at the time.[vi] In 1906 Flack published a study he had been working on at Johns Hopkins, Spanish American Diplomatic Relations Preceding the War of 1898 (Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins Press).

Flack rejected the argument that the United States was justified in going to war with Spain in what we would today call a humanitarian intervention, that is, to stop cruel Spanish war measures such as the reconcentration policy.

Cruel, indeed, agreed Flack, but it wasn’t appropriate for the American Union, if it valued consistency, to adopt a policy of humanitarian war. Concerning Spanish war cruelties, Flack responded:

“To the people of the South such acts are odious and call to mind Sherman’s march to the sea and through the Carolinas, and Sheridan’s orders to lay waste the Shenandoah Valley. These two acts, however much suffering and devastation followed in their train, have been justified, or at least tried to be justified, as necessary for military purposes, but who will deny that such acts were cruel? Was intervention of other nations justifiable on that account? The United States would have answered emphatically in the negative, but no nation ever intimated that such acts were cause for outside interference. There were many cruel, inhuman acts in the Civil War, as in all wars, but among civilized nations no country has ever assumed to interfere with war in another on account of cruel treatment or suffering resulting from the war. War is bad at its best, and when it assumes its worst form, General Sherman’s definition does not seem inappropriate….[French jurist Louis] Le Fur compares the devastation in Cuba to that of Sherman in Georgia and of Sheridan in the Shenandoah, and asks whether the latter justified European intervention.”[vii]

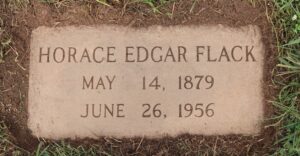

Two years later, Flack published his Fourteenth Amendment book, and later he became a well-respected legislative reference specialist for the Baltimore and Maryland governments. Flack died in 1956.

Regarding Flack’s Fourteenth Amendment book, had he changed his mind on the Civil War and Reconstruction as he contemplated the unpunished murder of his uncle’s alleged murderer? Or had he simply overcome his preconceptions and pursued honest scholarship, reaching what might have been the unwelcome conclusion that the Fourteenth Amendment was meant to strongly restrict the rights of the states?

When I contacted the Genealogical Society of Old Tryon Co., NC for this article, seeking photographs of Flack’s grave in the Mountain Creek Baptist cemetery in Rutherfordton, they most kindly obliged. Previously, the grave had been near-overgrown, but historical society volunteers uncovered the buried burial plaque.

Similarly, the sentiments Flack expressed in the aftermath of his uncle’s death were cleared away to reveal more clearly Flack’s discoveries in the Fourteenth Amendment.

Similarly, the sentiments Flack expressed in the aftermath of his uncle’s death were cleared away to reveal more clearly Flack’s discoveries in the Fourteenth Amendment.

[i] Horace Flack, The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1908). Part of the story of the influence of Horace Flack’s book in the Supreme Court’s discussion of incorporation of the Bill of Rights can be found in Noah Feldman, Scorpions: The Battles and Triumphs of FDR’s Great Supreme Court Justices (New York: Twelve, 2010). For a summary of Flack’s career, see “Dr. H. E. Flack, Ex-Law Data Chief, Dies,” The Baltimore Sun, June 27, 1956,

[ii] George Washington Paschal, History of Wake Forest College, Volume II (Wake Forest: Wake Forest College, 1943), 365-391. Flack’s membership in the Euzelian society is confirmed on p. 387.

[iii] Horace Flack, “Junior Thesis” (handwritten manuscript without page numbers), Wake Forest University Archives, Z. Smith Reynolds Library.

[iv] J. Timothy Cole, The Forest City Lynching of 1900 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishers, 2003. The familysearch family tree feature confirms that Horace was the nephew of Mills Higgins Flack, whose death triggered the lynching.

[v] Horace Flack, “The Old North State Forever,” The Wake Forest Student, Volume 20, No. 6 (March 1901), 366-380.

[vi] Robert Bunny Yoshioka, Westel Woodbury Willoughby, a Biography, PhD Dissertation, Syracuse University, 1971. Flack is referred to on pp. 115-16, n. 60 and accompanying text.