Commander-in-Chief at Civil War: Abraham Lincoln

ECW welcomes back guest author Kyle R. Hallowell

The Civil War wasn’t just fought on the battlefield; it was fought in the halls of Washington and Richmond, and victory there counted for as much, if not more, than on the field. Because war is inherently political, the hand guiding the apparatus of the state through war matters a great deal. If a state’s political leaders develop a flawed policy, it will have cascading effects on the conduct of all other operations. Therefore, the competence of the politicians leading that state matters more so than the competence of its generals. Because military and political power were combined in the role of commander-in-chief, the skills, personalities, and competencies of Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis were essential to their nation’s quest for victory.

From a legal perspective, Lincoln and Davis had the same enumerated powers as commanders-in-chief in their respective constitutions; in fact, the Confederate Constitution copied Article II, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution verbatim.[i] However, both men differed significantly in their personalities and the resources their nations had access to during the war. Whereas Lincoln ruthlessly exploited advantages to achieve aims, Davis, through his actions and inactions, squandered the Confederacy’s war-making ability.

“The first, the supreme, the most far-reaching act of judgment that statesman and the commander have to make is to establish by that test the kind of war on which they are embarking; neither mistaking it for nor trying to turn it into, something that is alien to its nature.”-Carl von Clausewitz

Lincoln’s most important role as commander-in-chief was determining the nature and character of the war his nation would fight and what national objectives he sought to achieve. His chief and enduring objective was preserving the Union, with the abolition of slavery and preventing recognition of the Confederacy by Britain and France as secondary objectives.[ii] Lincoln believed that the Confederacy was not an independent nation, but a collective rebellion of several states that could only be subdued by the reassertion of federal power into every corner of the Confederacy. Lincoln used every instrument of national power at his disposal to achieve these aims.

Lincoln jealously guarded his role as chief policymaker and ensured military, foreign, and economic policies complied with his vision. A clear example of this is Lincoln’s declaration of a blockade on Confederate ports.[iii] The blockade contributed to Union victory by combining naval, economic, and diplomatic power to reduce Southern exports, decrease civilian morale, undermine the Confederate government, and overwhelm inadequate Southern rail networks. To further erode the Confederacy’s war-making ability, Lincoln, against the advice of some cabinet members and military advisers, took the politically unpopular yet necessary action to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which sought to deprive the Confederacy of its most valuable economic asset and to prevent foreign intervention by unequivocally making emancipation a Union war aim.

One of Lincoln’s most vexing problems as commander-in-chief was getting recalcitrant subordinates to recognize his authority and ensure they complied with his policies. One of the ways he did this was by selecting and, in turn, removing military and political subordinates who did not support his war aims or superseded their writ by developing policy. Lincoln removed Maj. Gen. John Frémont from command for insubordination after he independently announced emancipation.[iv] He also ensured compliance with his orders by remaining highly informed about military operations. Lincoln practically lived in the War Department telegraph office, where he spent hours communicating with his generals. The Official Records of the War of Rebellion is replete with Lincoln’s correspondence with his commanders, in which he is constantly probing for information, praising victory, and admonishing lackluster performance, with some of Lincoln’s telegrams being as curtly worded as “How does it look now?”[v]

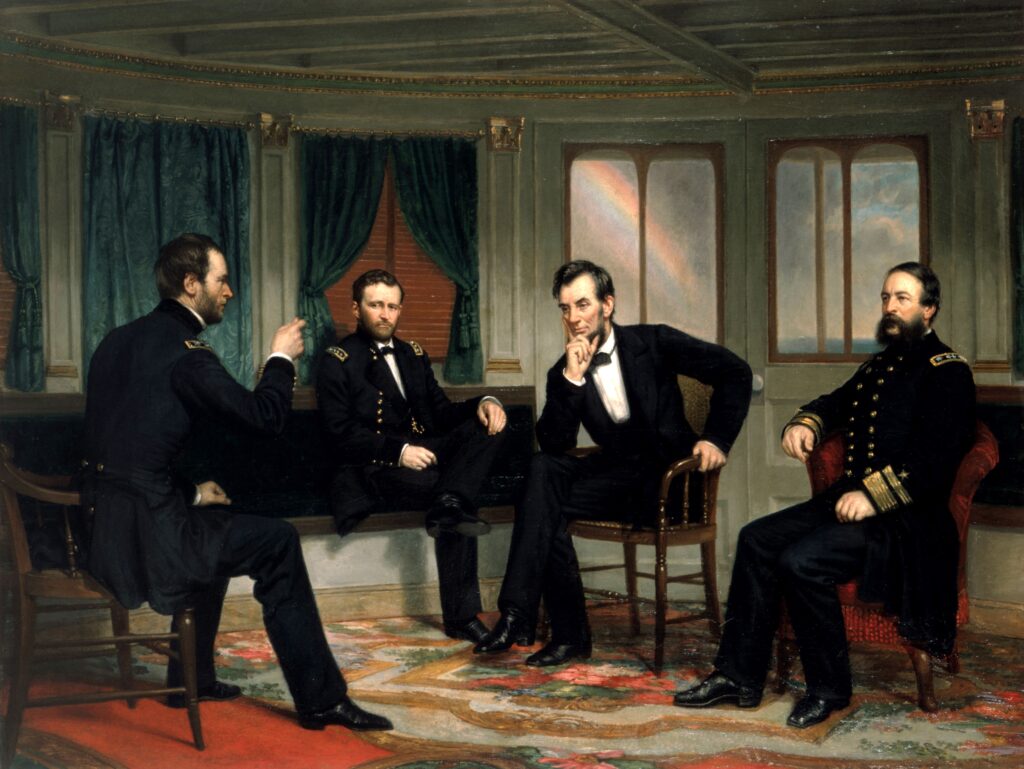

Despite marginal military experience, Lincoln entered office with several strengths, such as an autodidactic intellect, an ability to tolerate difficult subordinates, a willingness to listen to others, and self-awareness. Lincoln’s awareness of his inexperience was an advantage because it forced him to seek guidance from military leaders and educate himself on military matters.[vi] Lincoln, in contrast to Jefferson Davis, recognized that he lacked the recondite military knowledge to serve as his general-in-chief and perform his Presidential duties simultaneously. Therefore, he voluntarily reduced his power by appointing several talented men as general-in-chief throughout the war. In another contrast to Davis, Lincoln had a keen eye for human talent and possessed a deep bench of military and political subordinates. His appointments of Edwin Stanton, Henry Halleck, and Ulysses Grant, whose complementary strengths and weaknesses were crucial to victory, proved wise decisions. Despite their talents, Lincoln maintained control over the reins of power and ensured these three men complied with his orders. Most importantly, these appointments allowed Lincoln to focus on tasks that required his sole attention.

Unlike Davis, who did not have to manage domestic political parties, Lincoln had to manage a fractious coalition of radical Republicans, southern-sympathizing Democrats, border-state moderates, a cabinet of political rivals and opponents, and critical ethnic groups. To do this, he had to ensure that these groups were equally represented in government and high command, inoculating himself against charges by one party that the other was receiving all the military appointments. Notable Democrats such as John McClernand, Daniel Sickles, and Benjamin Butler became generals, along with Republicans such as John Frémont and Nathaniel Banks.[vii] Lincoln, despite the opposition of Stanton, wanted to guarantee the support of ethnic Germans by appointing Alexander Schimmelfenning as a brigadier general.[viii] To maintain the support of state governors and accumulate political capital, Lincoln took the risk of allowing the Union to implement an inefficient draft system where new regiments were raised instead of having recruits fill out the old ones depleted by battle, which had the negative effect of depriving new soldiers of the opportunity to learn from veterans.[ix]

Lincoln also had to appease the radical element of the Republican party, especially in the latter half of 1864 when the Confederacy sent representatives to negotiate peace. Word of this leaked to the public, which was depressed due to the seeming lack of military results and high casualties. Thus, it was amenable to peace, even if it meant denying emancipation. In August 1864, when the prospects of Union victory looked bleak, Lincoln had a meeting with Alexander W. Randall, the former Republican governor of Wisconsin, where he vociferously stated his opposition to the idea proposed by Northern Democrats to end the practice of allowing black men to be soldiers. Lincoln is quoted as saying:

“There have been men who have proposed to me to return to slavery the black warriors of Port Hudson & Olustee to their masters to conciliate the South. I should be damned in time & in eternity for so doing. The world shall know that I will keep my faith to friends & enemies, come what will. My enemies say I am now carrying on this war for the sole purpose of abolition. It is & will be carried on so long as I am President for the sole purpose of restoring the Union.” [x]

Despite this pressure, Lincoln did not back away from reunification or emancipation and followed his advice to “hold on with a bulldog grip.” Had Lincoln given way, it would have made him look impotent, undermined his support from Radical Republicans, and compromised his war aims.[xi]

General Douglas MacArthur said many years after the Civil War, “In war, there is no substitute for victory.” The Union was victorious in the Civil War, and one of the primary reasons for its victory was Abraham Lincoln’s leadership. Never before had an American president carried such a tremendous burden as Lincoln did as wartime commander-in-chief. For all his excellent qualities, the one that proved crucial to his success was his unwavering dedication to achieving his war aims. Lincoln clearly defined and articulated his aims and ensured that every sinew of national power was dedicated to accomplishing his goals. He truly was the indispensable man, and had he not been president, the war would have ended differently.

In my next post, I will evaluate Jefferson Davis as commander-in-chief and describe how he played a decisive role in the Confederacy’s defeat.

Kyle R. Hallowell is an active-duty U.S. Army Strategist currently studying International Policy at Texas A&M University. He has a BA in History from Norwich University and has been passionate about the Civil War since childhood. He lives in Northern Virginia with his wife and son.

Endnotes:

[i] Confederate States of America. President and J.D. Richardson, A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Confederacy, Including the Diplomatic Correspondence, 1861-1865 (United States Publishing Company, 1904), 9.

[ii] Lincoln brilliantly articulated his aims in the Gettysburg Address.

[iii] Abraham Lincoln, President Abraham Lincoln’s Union Blockade Proclamations, National Archives Identifier 620244 (National Archives: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685 – 2004, 1861).

[iv] The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1881), Ser. 1, Vol. 3, 467, 553; Herman Hattaway; Archer Jones, How the North Won: a Military History of the Civil War. (Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 270.

[v] OR, Ser. 1, Vol. 19, Part 2, 210.

[vi] Donald Stoker, The Grand Design: Strategy and the U.S. Civil War (Oxford University Press, 2010), 36.

[vii] T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and His Generals, (New York: Vintage Books 1952), 191.

[viii] Ibid, 11.

[IX] Eliot A. Cohen, Supreme Command: Soldiers, Statesmen, and Leadership in Wartime (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2003), 49.

[x] “Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Volume 7,” University of Michigan, accessed June 17, 2024, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln7/1:1109.1?rgn=div2;view=fulltext.

[xi] James M. McPherson, Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief (Penguin Publishing Group, 2008), 242.

In the 1860s, Lincoln was just as much a racist as every other white man in the United States. He made it very clear he would not go to war to free the slaves. His decision to issue the Emancipation Proclamation was a political decision to gain support from northern politicians and abolitionists to continue the war. Yes, he maintained the Union which is a great thing to accomplish. But to continue memorializing him as the savior of the black race is gratuitous at best. Lincoln was a very smart politician who used everything at his disposal to maintain the Union, including violating the Constitution and the Federal laws in effect during his administration. Every historian knows this quite well, but most continue with the early northern teaching that the war was caused totally to keep slavery and Lincoln went to war to end it. Why can’t we write the truth, the good and bad?

Jim,

I think you are reading into this post and taking things from it that are not there. I am not stating that Lincoln is the “savior of the black race.” I fully admit that Lincoln, as was commonplace in his time, was racist. He is on record as saying that blacks and whites are not equal and should live separately. However, Lincoln made it very clear that he thought slavery was morally wrong. Yes, Lincoln suspended habeas corpus for American citizens, thus violating the Constitution. However, I would argue that Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus was done to serve a higher purpose: the preservation of the Union and the Constitution itself. Numerous other Presidents, including FDR and Obama, would deprive individual Americans of their rights to protect the security and rights of all Americans. Preserving the “last best hope of earth” should not be shrugged off. The cause of the United States in the Civil War was a noble one that enjoyed international support, especially from those people smarting under the despotic monarchies of Europe, the rulers of which were eager to see the American experiment in self-government fail.

I do take issue with your statement that it is a “Northern teaching” to state that the principal cause of the war was slavery. These “Northern teachers” were fortunate to have primary sources to support their arguments. Documents such as the South Carolina Declaration of Secession and the Cornerstone Speech make it very clear that the southern states resorted to war to preserve their economic and social institution of slavery. Lincoln succinctly states this in his second inaugural address. Yes, arguments can be, and were made that economic, political, and social differences played a role, but all those disputes were soluble. Slavery was not. Lincoln correctly deduced that slavery was a threat to individual liberty. Having been politically active since 1846, Lincoln knew that all previous attempts to resolve the slavery issue had failed, thus making it the primary cause of the war. Historians such as David M. Potter and Gary Gallagher have addressed this topic at length.

Good article! One disagreement: The US Army’s reliance of raising fresh “green” regiments as opposed to building up veteran regiments was a serious drawback that the Confederates managed to (in part) avoid. Second point: one of the reasons that Lincoln pushed the abolition is that he hated slavery. But in the context of fighting the Civil War, its not just that slavery was wrong. Slavery was also what was wrong with the United States, and had to be eliminated in order to remove the root cause of secession for all time.

Hi Matt, I am glad that you enjoyed the article. I don’t think that we disagree. Lincoln’s decision to create new regiments was militarily problematic, but his decision supports the main point of the post, which is that Lincoln subordinated military interests to political interests to achieve his aims. I do agree that Lincoln hated slavery, and he made that clear on several occasions.–“A House divided against itself cannot stand.”

To expand the draft system point further, the Confederacy managed to mobilize close to 80% of its eligible male population and keep them in uniform for the duration of the war. Talk about an asymmetric advantage for the Confederacy.

Sorry, but you are, in my opinion, drawing conclusions from the ultimate results, results that Lincoln’s continuing bunglings AFTER THREE YEARS AT THE HELM nearly squandered. He had a much fuller deck to play with, but by July, 1864 he himself was convinced he was doomed.

Very interested in your comments about Davis and his cabinet

Hi Joe,

Please check out the post that went up today!

Great essay … and you’ve cited some of my favorite works on civil-military relations – Cohen, Williams, and McPherson … Lincoln had a steep learning curve, but by 1863 he had all the qualities of an effective wartime leader: common sense, intuition, ability to judge human character, the knack for asking hard questions and challenging assumptions, the ability to connect military matters into the strategic political outcomes, et al.

Perhaps his Lincoln’s greatest trait was his understanding that civil-military relations must be, when Cohen calls, a dialogue of unequals … that the President was ultimately responsible for outcomes and must exercise leadership when needed – questioning, interrogating, probing, directing and sometime dictating.

As Cohen writes in Supreme Command “It is always right to probe … politicians should make no apologies for putting their military subordinates under severe pressure because war is a business of terrible pressures.”

Thank you Sir. I am glad that you enjoyed reading it! I think Cohen’s book is canon that will endure in its importance.

I really enjoyed your essay. I heartily agree with your assessment of Lincoln. The only point I would disagree with is the statement regarding Alexander Schimmelfennig (hope I got that spelled correctly). I think the appointments of Franz Sigel and Carl Schurz had a bigger impact on retaining Germans.