Colonel Thomas Jackson, a Navy Chaplain, and “False Faith”

ECW welcomes guest author Samuel Limneos.

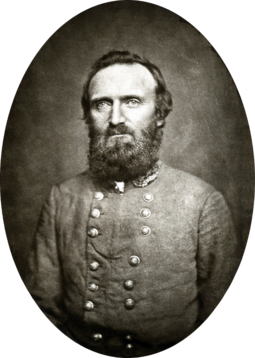

From the ridgeline along Maryland Heights in mid-May 1861, Col. Thomas Jackson looked over the winding Potomac River that wrapped itself around the quaint town of Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Jackson surveyed the town and surrounding encampments where nearly 4,000 Virginia militiamen, many of whom had seized the arsenal from the U.S. Army a month earlier, now lived under the colonel’s strict discipline. Jackson was already in communication with the chief commander of Virginia’s military forces, Gen. Robert E. Lee, who had ordered the colonel to remove the armaments and artillery stored at Harpers Ferry to the new southern capital of Richmond, Virginia. From his position at Harpers Ferry, only the 800-foot width of the Potomac River separated the United States of America from the newly formed Confederate States of America.[1] As he peered over the scene, Jackson noticed a pair of visitors trudging their way toward him up the ridgeline.

Less than two years earlier John Brown, an abolitionist partisan and veteran of the bloody guerilla combat that wrecked Kansas during the 1850s, led a contingent of twenty-one whites, as well as free blacks and fugitive slaves, in an assault on the federal arsenal at the town. In December 1859, Jackson led the artillery component of a security detail of cadets from the Virginia Military Institute – where he worked as instructor – presiding over Brown’s execution at Charles Town, Virginia.[2] Jackson had only recently been assigned by the Virginia armed forces to duty at Harpers Ferry. On April 17, 1861, the Virginia Convention voted to secede from the United States, and in late April the Virginia governor ordered Jackson to assemble a command at Harpers Ferry, the strategic town along the Potomac at the border between the Old Dominion State and Maryland.

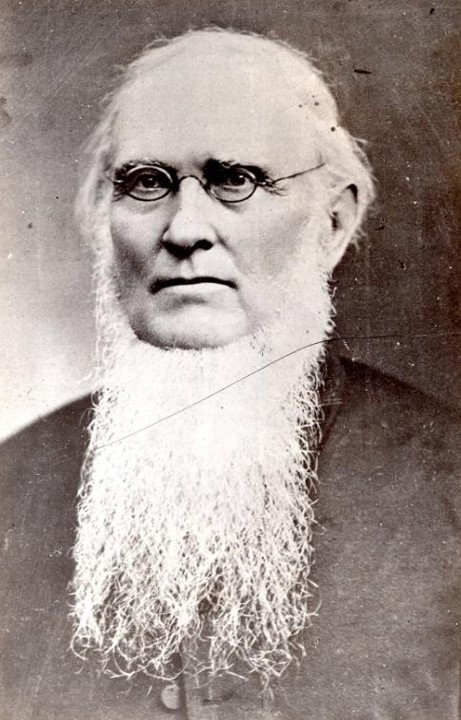

Jackson recognized the visitors approaching Maryland Heights as his loyal friend and subordinate, George G. Junkin, and the young man’s father, David Xavier Junkin, a grandfatherly looking elder behind thin spectacles, with a long face-framing white beard. Dressed in the simple, long blue coat of a United States Navy chaplain, the elderly Junkin was well received by Jackson, who was still wearing his dark blue uniform with the rank of colonel of Virginia infantry.[3] A Pennsylvania native and Presbyterian minister educated at Lafayette College, the 53-year-old Junkin was commissioned as a Navy chaplain just two weeks after John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry. After a short tour at Philadelphia, Junkin received orders to the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, where he took up the post of chaplain in January 1861.[4]

Junkin came to Annapolis with complex familial ties. His son, George, became close friends with Jackson while a student in the Class of 1859 at Washington College, which shared a home at Lexington, Virginia with VMI. For his part, Jackson had close ties to the Junkin family. In winter 1852, Jackson became engaged to a beautiful young lady he met at Lexington’s local Presbyterian Sunday School: Elinor Junkin, the daughter of George E. Junkin, the president of Washington College and brother to Chaplain Junkin. After marrying and spending a happy year together in Lexington, Elinor died in childbirth shortly after the newlyweds’ one-year anniversary, a tragedy that deeply affected Jackson. The bereaved Jackson remained close with his late wife’s family, even living with them at George E. Junkin’s residence on the Washington College campus until he remarried in 1857. For two years, young George G. Junkin and Thomas Jackson were constantly together.[5] After John Brown’s raid, young George, Chaplain Junkin’s son, enlisted in a Virginia volunteer unit. When Virginia seceded from the United States, George made his way to Harpers Ferry to join up with his friend and former mentor.

Worried that his son was making a grave mistake, Chaplain Junkin hurriedly left Annapolis for Harpers Ferry. The three met atop Maryland Heights. For more than two hours, Chaplain Junkin used every oratorical skill he possessed trying to convince Jackson and his own son that the growing Southern secession movement was “a rebellion without a cause.” The newly inaugurated President Abraham Lincoln sincerely wanted to govern according to the Constitution, Junkin promised, and harbored no intentions to unilaterally abolish slavery in the southern states. All that southerners had to do was await a Democratic majority in Congress to secure their rights, Junkin argued. He reasoned that even a successful rebellion would eventually speed up slavery’s ultimate destruction on the continent.

Looking inevitable after the firing on Fort Sumter on April 12, the looming conflict between North and South, Junkin prophesized, “would inaugurate the wars of a hundred generations in America, and repeat the bloody history of Europe.” Jackson quietly listened to Junkin’s pleadings. “As a Christian man, my first allegiance is due to my state, the state of Virginia; and every other state has a primal claim to the fealty of her citizens, and they may justly control their allegiance,” Jackson told Junkins. “If Virginia adheres to the United States, I adhere. Her determination must control mine.” Chaplain Junkin poignantly described the scene:

“The time arrived that we must part. None were present but my poor boy, the General, myself, and our God. He held his magnificent field horse by the bridle-rein. His left hand was gauntlet-gloved. He grasped mine with his right. I said, ‘Farewell, General; may we meet under happier circumstances; if not in this troubled world, may we meet in’ – my voice failed me, – tears were upon the cheeks of both, – he raised his gloved hand, pointed upward, and finished my sentence with the words – ‘in heaven!’ And so, without another word, we parted; he mounted and rode away.”[6]

While lamentingly bidding his son and ex-nephew-in-law Jackson farewell at Harpers Ferry, on his ride back to Annapolis Chaplain Junkin lamented the fate and dire state of the country. David Xavier Junkin, Jackson’s former uncle-in-law, a Navy chaplain and fellow Presbyterian, had tried in vain to convert the future Confederate general and his own son from their unshakeable faith in state allegiance. “It was in vain we argued with him that this doctrine was false, disintegrating, destructive of all possible nationality,” Chaplain Junkin later wrote. “Like Paul when he persecuted the church, they verily thought they ought to obey each the behests of the State to which they owed allegiance. Their sin lay in a false faith.”[7]

Samuel Limneos is a government archivist and naval historian whose research focuses on military education, archives, artifacts, and the writing of history, as well as 19th and 20th century naval, military, and African American history. His work has appeared in the Journal of Military History, as well as Naval History and Army History. He is currently deputy director of the Navy Archives, and a former archivist at the U.S. Naval Academy.

Endnotes:

[1] Mark A. Snell, West Virginia and the Civil War: Mountaineers are Always Free (Charleston: History Press, 2011), 45-46.

[2] Charles P. Poland, Jr., America’s Good Terrorist: John Brown and the Harper’s Ferry Raid (Philadelphia: Casemate Publishers, 2020), 179-180.

[3] Snell, West Virginia, 45-46.

[4] Clifford Merrill Drury, United States Navy Chaplains, 1778-1945, Volume III – Biographical and Service-Record Sketches (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1948), 142.

[5] Addey Markinfield, Stonewall Jackson: The Life and Military Career of Thomas Jonathan Jackson (Scituate, MA: Digital Scanning, Inc., 2001), 23-24; W.G. Bean, “The Unusual War Experience of Lieutenant George G. Junkin, C.S.A.,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 76, no. 2 (April 1968), 181-183. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4247391.

[6] David X. Junkin, George Junkin, D.D. LL.D., A Historical Biography (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1871), 552-556. Of note, there is a scene in the film Gods and Generals that borrows some of this text and situation.

[7] Junkin, George Junkin, 556.

Well done sir

For those wondering what happened to the Chaplain Junkin’s Confederate son George, I highly recommend the reference in note 6 — it’s an interesting story …. if you can’t get access, here’s the reader’s digest version.

George, a Lieutenant on Jackson’s staff, was captured at the Battle of Kernstown during the Valley Campaign … his father petitioned the U.S. War Department for a parole, but was turned down … instead, George was offered his freedom if he swore an oath of allegiance to the United States … ever the proud confederate, George refused … the Chaplain again intervened, telling George that his mother was critically ill and her dying wish was to see her son … George relented, took the oath, and visited his dying mother who had miraculously recovered.

George, miffed about his father’s deception, headed south seeking his old position on Jackson’s staff … the position was filled so George joined the 25th VA Cav. and served as Captain through the rest of the war … post-war, George had a distinguished career as a commonwealth attorney, superintendent of schools, judge, and trustee at Washington and Lee University … he died in 1895.

And that, as radio commentator Paul Harvey used to say, is “the rest of the story.”