The 1864 American Insurrection That Wasn’t: Presidential Election Day and the New York City Fires

ECW welcomes back guest author Stephen Romaine.

As the Civil War dragged on, northern opposition grew despite consequential victories in 1863 at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. By June 1864, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s army slogged its way to within twenty-five miles of Richmond. Critics argued the cost was too high, allowing “thousands of brave men to be slaughtered in vain.”[1] On August 23, 1864, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to his cabinet regarding the transition to a new president-elect. He filed it to be shared the day after the upcoming election, assuming he would lose.[2]

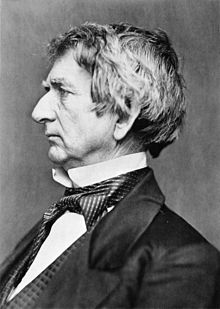

In the meantime, a shadow war had begun. William H. Seward, Lincoln’s secretary of state, was orchestrating a cross-border counter-insurgency against Confederate-sponsored terrorists from Canada. While Seward has been credited as the president’s “indispensable man,” his efforts in this regard are less well known.[3]

After consulting with Secretary of War James Seddon and Secretary of State Judah Benjamin, by March 1864, Confederate President Jefferson Davis approved a clandestine plan to provoke insurrection in the North.[4] Former US Interior Secretary Jacob Thompson would lead a team of escaped Rebel prisoners. One million dollars in Confederate gold was allocated for Canadian secret services.[5]

After a failed attempt by Confederate agents to instigate a rebellion across midwestern states in August 1864, Lincoln and Seward feared additional attacks. Before summer ended, Seward had a double agent, Richard Montgomery, passing dispatches between Richmond and Toronto. Stopping in Washington, Montgomery’s messages were decrypted. He provided early warning on plans to target principal northern cities with arsonist attacks for the purpose of inciting insurrection. He later testified that he was aware New York City was one of the primary targets but did not learn specifics until days before the November election.[6] The prospect of an insurrection in New York, where the previous summer draft riots tragically killed hundreds of African Americans and the governor opposed Lincoln, was concerning.[7]

Seward met on September 25, 1864, with Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler for two hours of undisclosed conversation. Surely Seward did not seek out the general for a “friendly chat,” as Butler later suggested.[8] It probably had to do with the intelligence-gathering capability he established a year before with the abolitionist Elizabeth Van Lew.[9]

Not knowing all the details but suspecting another impending terrorist event, Seward traveled to the general’s field headquarters in Virginia. What information was confirmed, disclosed, or requested at this meeting is not known, but after New York officials dismissed Seward’s warning as a “hoax,” he asked Grant to send Butler to New York City.[10]

Leader of a Richmond spy ring, Van Lew placed an agent in the Confederate White House in the role of a enslaved housemaid in 1863. Mary Bowser, a freed Van Lew slave, was taught to read and write by Elizabeth and sent North to a Quaker school before returning to Richmond.[11] Mary was in a unique position to spy on Jefferson Davis, who often worked from and held conference in his home office.[12]

The Confederate-funded plan devised in Canada was to set Manhattan hotels ablaze with incendiary devices first developed in a Richmond lab. A core team of escaped Rebel prisoners would ignite the fires on election day, November 8, 1864, with other cities to follow.[13]

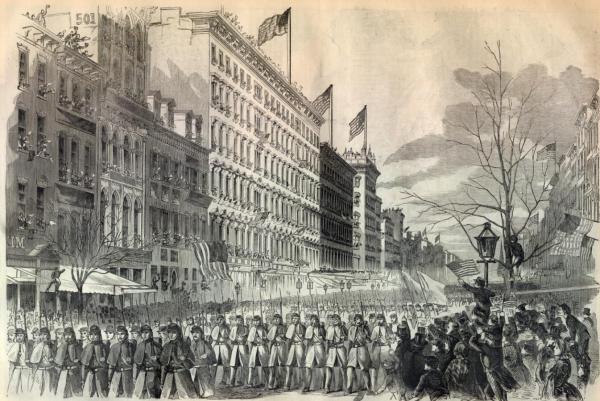

Before the conspirators could act, Butler marched Union soldiers into the city. One of the terrorists later penned, “The leaders in our conspiracy were at once demoralized by this sudden advent of General Butler and his troops. They felt that he must be aware of their purposes.”[14] The planned attack was called off. President Lincoln won reelection with 55 percent of the popular vote, defeating his former general, George B. McClellan. Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s capture of Atlanta swayed additional votes.[15]

Confederate agents tried again after Butler left on Evacuation Day, November 25, 1864, celebrating the British leaving New York in 1783. Hotels along the Manhattan parade route were targeted. This time, after a second warning was provided in advance, police and fire fighters were placed on high alert.[16] The source was most likely a disgruntled conspirator turned informer.[17] Fires either failed to ignite or were extinguished in approximately thirteen hotels with minimal damage and no loss of life.

As noted in “Secret Service of the Confederacy,” published by the Signal Corps Association, “Every Confederate plot in the North was fated to fail.”[18] Ineptness, poor planning, and last-minute loss of nerve contributed to the failure of this and other Confederate-funded attacks. Preventive efforts certainly played a critical role and were not merely a series of one-off local responses, as often suggested. In December 1864, Jacob Thompson wrote from Canada to Judah Benjamin, “The bane and curse of carrying out anything in this country is the surveillance under which we act. Detectives, or those ready to give information, stand at every corner.”[19]

The little we know concerning the intelligence Richard Montgomery obtained comes from his post-war testimony during the trial of Lincoln’s assassins.[20] Consensus holds that whatever specific intelligence Mary Bowser passed to Van Lew and shared with the Federals has been lost to history. Lack of evidence does not imply a lack of effectiveness of those engaged in espionage. Good spies cover their tracks. It is a life-saving prerequisite. Van Lew destroyed information, including communications she requested back from Washington after the war. Almost half the pages from Elizabeth Van Lew’s recovered diary were destroyed, apparently to hide spying activity. However, a May 1864 Van Lew entry in recovered pages reads, “When I open my eyes in the morning, I say to the servant, what news, Mary? and my caterer never fails.”[21]

Mary Bowser continued to hide her past, moved often, and used different names her entire life. Her cover being blown, during or after the war, would have put her life in imminent danger. Elizabeth Van Lew, a profoundly religious woman, did not reveal her placement of a spy in the Davis household until she was on her deathbed in 1900. Mary Bowser’s name was not disclosed until eleven years later in Harpers Monthly.[22]

After the war, Ulysses Grant told Elizabeth Van Lew, “You have sent me the most valuable information received from Richmond during the war.”[23] Elizabeth relied on slaves and former slaves passing encrypted messages across enemy lines to Grant’s headquarters.[24] As president, Grant made her postmaster of Richmond. She lived the rest of her life shunned by former friends and neighbors, no longer welcome at her beloved place of worship. Her gravestone was desecrated.[25]

The desire to expedite the reinstatement of the secessionist states helped obscure associated events related to attempted insurrection. The Supreme Court dismissed charges against the captured Midwest collaborators after the first failed attempt.[26] Many other conspirators were never brought to justice. Pardons were granted. Only one of the New York City terrorists was sentenced and hung for violating the laws of war.[27]

Seward’s counter-insurgency campaign, with help from the US Army, spies, and detectives from Canada to Richmond, disrupted Confederate efforts to terrorize New York and other northern cities. The combined efforts of Elizabeth Van Lew, Mary Bowser, Richard Montgomery and other clandestine war heroes helped prevent a rebellion that could have derailed Lincoln’s reelection, led to the permanent dissolvement of the Union, and ensured that the Confederate brand of slavery remained intact, possibly for decades to come.[28]

Stephen Romaine is author of Secret Army Behind Enemy Lines. He was the keynote speaker at the Society for Women and the Civil War July 2023 Conference. His topic, “Elizabeth Van Lew, Mary Bowser and the Richmond Underground,” was subsequently published by the Society in their quarterly At Home and in the Field e-journal.

Endnotes:

[1] “The Situation. The Great Question – Should Lincoln be Reelected?,” New York Herald, (June 10, 1864).

[2] “Letter from Abraham Lincoln to his Cabinet Members” Library of Congress, (August 23, 1864) https://www.loc.gov/resource/msspin.pin2201/?st=gallery

[3] Walter Star, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man, (New York: Simon & Schuster; 2013), 546.

[4] John Breckinridge Castleman, Active Service, (Louisville: Courier-Journal Job Publishing, 1917), 134-137.

[5] Margaret E. Wagner, Gary W. Gallagher and Paul Finkelman, Eds. Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002), 453.

[6] Benn Pitman, Ed, The Assassination of President Lincoln and the Trial of Conspirators (New York: Moore, Wilstach & Baldwin, 1865), 25.

[7] “The Draft,” New-York Tribune, (July 14, 1863).

[8] Benjamin F. Butler, Correspondence of Gen. Benjamin F. Butler (Bellevue: Big Byte Books, 2014), Vol. 5, Kindle Edition Location, 4551.

[9] David D., Ryan, Ed, A Yankee Spy in Richmond the Civil War Diary of “Crazy Bet” Van Lew (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2001), 51.

[10] Butler, 8619

[11] Ibid, 11.

[12] James M. McPherson, Embattled Rebel: Jefferson Davis and The Confederate Civil War (New York: Penguin Books, 2015), 7-9, 112.

[13] John W. Headley, Confederate Operations in Canada and New York (New York: The Neal Publishing Company, 1906), Kindle Edition Location, 4574.

[14] Ibid, 4552.

[15] Wagner, 223-224.

[16] “The Plot,” The New York Times, (November 27, 1864); Jane Singer, The Confederate Dirty War, (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc. 2005), 65.

[17] Headley, 4736; Singer, 89.

[18] “The Secret Service of the Confederacy,” Signal Corps Association 1860 to 1865, (Glen Burnie), http://www.civilwarsignals.org/pages/spy/confedsecret/confedsecret.html

[19] The War of the Rebellion: The Official Records of the Union and confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 43, Part 2, 934.

[20] Pitman, 24-26.

[21] Ryan, 94.

[22] Beymer, William Gilmore. “Miss Van Lew.” Harpers Monthly, (June, 1911), 86-99.

[23] Peter G. Tsouras, Major General George H. Sharpe and The Creation of American Military Intelligence in the Civil War, (Philadelphia: Casemate, 2018), Kindle Edition Location, 7134.

[24] Ryan, 108, 116-117.

[25] Ernest B. Furgurson, Ashes of Glory, Richmond at War. (New York: Vintage Civil War Library, 1996), 361.

[26] James D. Horan, Confederate Agent, A Discovery in History, (Auckland: Pickle Partners Publishing, 2015), 483.

[27] Singer, 70-72.

[28] Tony Horwitz, “150 Years of Misunderstanding the Civil War,” The Atlantic, (June 19, 2013) https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/06/150-years-of-misunderstanding-the-civil-war/277022/

Very interesting. You write: “Only one of the New York City terrorists was sentenced and hung for violating the laws of war.” Who was that unfortunate, and why him?

Kevin, only one of the conspirators was arrested after the arsonist attack by detectives who had followed him from Toronto. Another conspirator traveling with him managed to slip away.

Thank you. A very interesting story.

“The Confederate brand of slavery would remain intact, possibly for decades to come”….it’s acknowledged that slavery would have ended at least by the 1880s. so for those who think the North fought to end slavery, consider that c. 700,000 people died in that event. But, while slavery was an issue of that day, it wasn’t the reason for the War, so c. 700,000 people died to prevent the U.S. from losing its tariff revenue and the South from being able to establish free trade, neither of which would have been a problem for the U.S. or anyone else if Lincoln had been willing to negotiate.

My antenna goes up when a writer speaks in the third person … for example, your statement ” … it’s acknowledged that slavery would have ended at least by the 1880s … ”

What historian — no fringe weirdos or post-war Lost Causers please — acknowledges that slaveholders would have willing ended the institution by the 1880s … and if slavery was on its last legs, what was the rationale for secession after the 1860 election?