Unexpected San Juan Run-In with President Lincoln

The same trip that brought me to Key West earlier this summer also took me to San Juan, Puerto Rico. The city is fantastic. My wife Brittany and I spent days touring the old Spanish fortifications, walking the picturesque streets, and feasting on beans, rice, piña coladas (at the site where they were invented no less), and mallorcas. One might think that there was not much to see related to the Civil War in San Juan, and indeed I was not expecting anything at all, but much like I did when visiting London two years ago, I stumbled upon a statue of Abraham Lincoln.

Out hotel in Old San Juan overlooked a square with a view of the Cathedral Basilica Menor de San Juan Bautista, where Ponce de Leon is buried, and was only a few blocks from both the vast Spanish colonial fortifications and the Lincoln statue. This statue sits at the southwest corner of Abraham Lincoln Elementary School, at the intersection of Calle Del Sol and Calle José Celso Barbosa. The statue has Lincoln sitting in the center. On one side of the president appears to be ancient Greeks, celebrating Lincoln as a champion of democracy. On the other are enslaved people offering Lincoln gifts as their liberator.

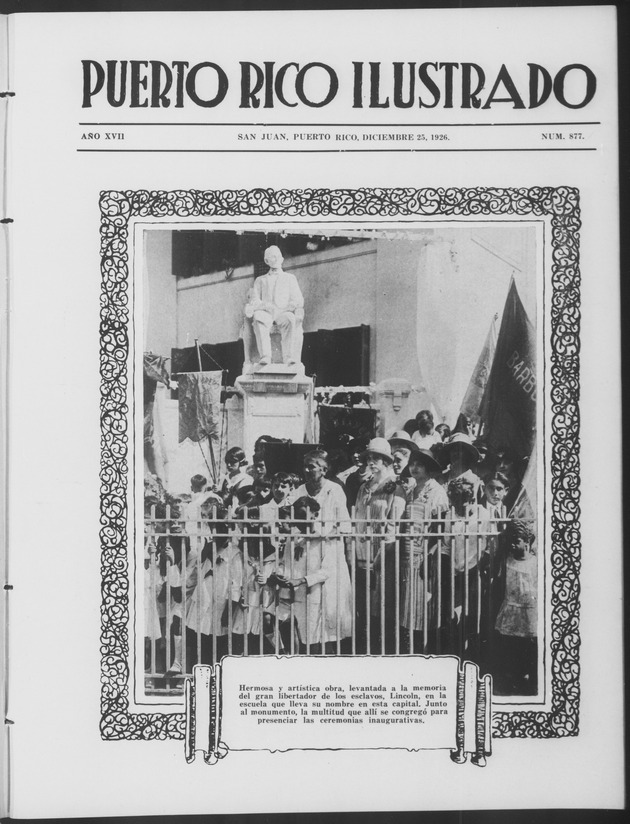

An inscription at the statue’s base explains it was erected in 1926 with funding from students, teachers, and local educational benefactor Rosario Andraca Contray de Timothée. Rosario herself had been a teacher in San Juan since the 1880’s, when Spain’s flag still flew over the island.[1] A 1926 newspaper called her a “la incansable educadora” – the tireless educator.[2] She helped organize balls held at San Juan’s municipal courthouse to raise funds for the project.[3]

The statue was unveiled in late 1926 to crowds packing the streets. There was a grandstand built across the street where local leadership gave speeches to a crowd of locals and school children to commemorate the day. One newspaper even insisted that Puerto Rican people as far as New York City celebrated the day.[4]

After seeing the statue, I started researching to see if there were other connections between the U.S. Civil War and Puerto Rico. Though there were no battles on the island, United States naval forces visited it during the war. These were mostly ships of the West India Squadron, searching for Confederate commerce raiders. One such case was USS Connecticut, which visited San Juan in early 1863.[5] Besides Lincoln Elementary, I also learned there was an elementary school named to honor David Farragut in Mayagüez that closed in 2021 and a school in Cabo Rojo named to honor Confederate Congressmen (and postwar U.S. minister to Spain) Jabez L.M. Curry that was renamed in 2023 to honor formerly enslaved woman María Civico.[6]

In trying to find other links, I also found a Sons of Confederate Veterans website honoring Hispanics who fought on both sides of the Civil War, claiming that a Confederate soldier designed the modern-day Puerto Rican flag. The site states that Cuban-born Ambrosio José Gonzáles, who served with P.G.T. Beauregard as a colonel in Charleston during the war, later helped designed the flag.[7] Gonzáles’s biography does mention he helped design the Cuban flag, and both flags have a similar design pattern, with different colors. Thus, Gonzales may have indeed either helped design or, at the very least, influenced thinking on a design for Puerto Rico’s flag.[8]

The only other links to the Civil War involve modern questions of territorial sovereignty. Puerto Rico is a territory of the United States and debates about granting either independence or statehood pervade. Organizations favoring Puerto Rican statehood use the Civil War as a case study to demonstrate that independence-movement organizations within the territory have no standing, as the Civil War proved the Union of states (and territories) is dissoluble (though perhaps they should also consider that the United States did allow independence of previous territory such as the Philippines, though that opens up a 20th century can of worms regarding incorporated versus nonincorporated territory status).[9]

It just goes to show that there are subtle links to the U.S. Civil War across the globe. I for one, am wondering where my next unexpected encounter with an Abraham Lincoln statue will take place and looking forward to when it happens.

Endnotes:

[1] “Secretaria,” Gaceta de Puerto Rico, Febraury 25, 1888, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

[2] “En La Escuela Lincoln,” El Imparcial, May 6, 1920, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

[3] “A Beneficio De La Estatua De Lincoln,” El Mundo, February 21, 1925, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

[4] “Sumario del Numero de esta Semana de “Puerto Rico Ilustrado,” El Mundo, San Juan, Puerto Rico, December 23, 1926.

[5] Boggs to Welles, March 6, 1863, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Ser. 1, Vol. 3, 447.

[6] Margaret M. Asencio-Lopez, “Confederate Memorial in Puerto Rico,” Portside, February 8, 2024.

[7] Hispanic Heritage Month: Hispanics in Gray and Blue, https://scv.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/hispanichistory-1.pdf, accessed July 12, 2024.

[8] Antonio Rafael del la Cova, Cuban Confederate Colonel: The Life of Ambrosio José Gonzales, (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1993), 20.

[9] “’Confederacy’ and ‘Commonwealth’ in America: A Parallel History of Failed Sovereignty,” PR51st, November 22, 2017, https://www.pr51st.com/the-commonwealth-and-the-confederacy/, Accessed July 12, 2024.

Neil mentions the link between the Civil War and Puerto Rico’s territorial status following its annexation by the US after the Spanish-American War. Here’s a physical manifestation of that link! George Boutwell was Abraham Lincoln’s first Commissioner of Internal Revenue in 1862-63 helping raise needed funds for the Union war effort. Forty years later he was President of the Anti-Imperialist League, working with Mark Twain, Andrew Carnegie, William James, and others to protest McKinley and Teddy R. acquisition of Puerto Rico and preventing either independence or statehood. In between George was Congressman, Senator, and Grant’s Treasury Secretary, helping write 14th and 15th amendments, impeach Andrew Johnson, and lead Senate investigation of white supremacist violence in Mississippi in the 1870s. My bio on George being published by WW Norton in January 2025. http://www.jeffreyboutwell.com