Initials or Nicknames Out of Some Now Incomprehensible Affection

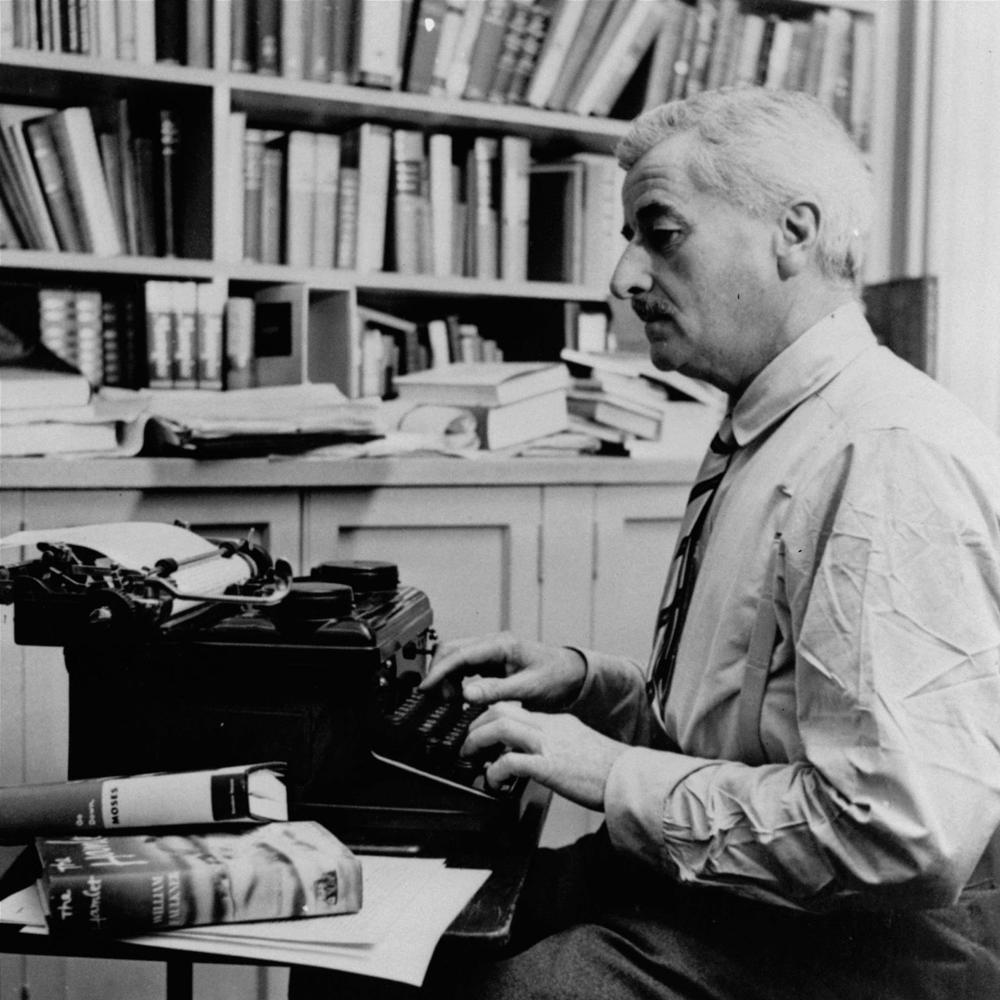

I just finished reading William Faulkner’s masterpiece Absalom, Absalom! It is a remarkable novel. Heavy in both subject matter and style, it’s not the kind of book you curl up with for some light entertainment, but it’s as insightful about the Old South as anything I’ve ever read. I highly recommend it to anyone up to the challenge.

The Civil War haunts the book through and through, but one particular part jumped out at me because it reminded me, in a way, of being a Civil War historian. Quentin Compton, a young man from Mississippi who serves as the book’s ersatz protagonist, is talking with his father, who shares an insight about the Old South:

We have a few mouth-to-mouth tales; we exhume from old trunks and boxes and drawers letters without salutation or signature, in which men and women who once lived and breathed are now merely initials or nicknames out of some now incomprehensible affection. . . . They are there, yet something is missing; they are like a chemical formula exhumed along with the letters from that forgotten chest, carefully, the paper old and faded and falling to pieces, the writing faded, almost indecipherable, yet meaningful, familiar in shape and sense, the name and presence of volatile and sentient forces; you bring them together in the proportion called for, but nothing happens; you re-read, tedious and intent, poring, making sure that you have forgotten nothing, made no miscalculation; you bring them together again and again nothing happens: just the words, the symbols, the shapes themselves, shadowy and inscrutable and serene, against that turgid background of a horrible and bloody mischancing of human affairs.

And gosh, isn’t that, in a way, reminiscent of being a historian? We literally exhume old letters from forgotten places and try to resurrect, in a way, people who once lived? We try to breath new life into them through the words they’ve left us, through the tales we uncover, through the records that exist.

Yet something is missing. We try to piece their lives back together, recreating something meaningful and familiar, but something is always missing. And we puzzle and puzz ‘til our puzzlers are sore, but in the end, all we really have are the words, inscrutable, written against the backdrop of the war.

Yes, I’m waxing poetic. Perhaps I’m reading with too much sentimentality for what we, as historians do, or for those lost men and women whose lives we try to recreate. There’s a sadness to it all because we’ll never fully succeed, and those lives will remain as shadowy and inscrutable as the words they’ve left behind. Yet we still love it. We love these stories. We love what we do. At least I hope most historians do, although I shouldn’t speak for everyone—but how hollow the whole task would be if you didn’t love it.

Faulkner’s passage reminds me of the wonder of what we do, the wonder of the creative process, the wonder of those lives that touch us, across the ages, through those tales and letters.

Chris, what a sad and someways disheartening commentary on your reading of Faulkner’s passage and the way you tie it with your view of a historian’s plight. It seems to me that as a reader and interpreter of history, you are never satisfied, you never reach the end of the story. Something is always missing. The answer maybe found over the next hill or over the next trench line, but in walking up that now just a bump in a wooded field, the answer still eludes you. Then, I think,the “answer” is not what a historian should be striving for, he should be asking instead what these events and individuals who participated in these momentous mean to me.

I’m often reminded of the motto embraced by Goddard College, where I did my MFA: It’s the journey, not the destination. I think that speaks to your idea that it’s not “the answer” we seek but rather the process of finding the answer that’s important. We might not ever be able to know all there is to know about the people we write about, so we just have to do justice to them as best we can with what we have. The important thing is the good-faith effort at doing them justice.

It must be September. Chris has time for heavy reading.

I will be thinking about your essay for a while. This may be one of the places where being a writer of fiction is easier than being an historian. If you can’t penetrate behind the words, you can always make stuff up. In fact, that is what a fiction writer is supposed to do.

Yeah, Faulkner’s not light reading–but well worth the effort!

Talk about a run-on sentence!

I think Faulkner may have been the king of run on sentences.

I have to resist picking up my editor’s red pen whenever I read him.

Ah, but it’s punctuated so brilliantly. The sentence DOES what it’s describing, all that coming together, again and again, without firm, defined results….

I’m reading John Lewis Gaddis’s “The Landscape of History” right now, and he makes a similar conclusion. We, as historians, can’t recreate it replicate the past, so we must “approximate” it. That doesn’t preclude the worth of the profession in general, but it does acknowledge that there will always be gaps, and we will never be able to create a “perfect image” of the past.

I’m tempted to go back to Whitman’s famous line, “The real war will never get into the books.” There’s too much of it, just as there’s too much to these people. We can only get at it, even if we can never get it exactly and completely.

Some things never change, and are as true today as they were yesterday, yesteryear, yesterEver. “If this be error and upon me proved, I never writ, nor no man ever loved.” William Shakespeare

Hard to cap the Bard. That is a great response to Chris’ lament. Thank you.

I definitely fall into the “No one beats the Bard” camp. That’s not a knock on anyone. Shakespeare was just a writer in his own class!

Time for you to read “An Odor of Verbena.”

“The task of historians is to describe the past. The tools we use are words. The words we choose: that is a moral choice.”

John Lukacs

What a great quote (and so true!).

That is a great excerpt to present. In writing my own book, ‘Till The Stars Appeared,’ I have found endless joy, but also puzzlement and frustration, in piecing together full story from what is presented in a spectacular diary that is the centerpiece of the story. Where there are factual errors it is easy to correct the story, but where there are unexplained gaps and occurrences that are difficult if not impossible to explain or find evidence that explains them. it can be difficult labor, but every second is a labor of love. It has led me, as well, to a new perspective on writing history. As I state in an early chapter of the book:

“Only the Dead can write history. We sift and sort the facts and records, the official and personal accounts from the past, analyze what happened, conject what a general was thinking, how he hit upon a brilliant or daring maneuver or why he made a terrible error; many even do what is common now – dishonestly revise it so that a 21st century political ideology of dubious legitimacy can magically revise the truth of what occurred in the 19th century – or worse, simply erase it. But ultimately this is not writing history – it is merely writing about history. History is written by those who made it, or were there to witness it. It is impossible – and a great conceit – for us to think we can write history, for only the Dead can write history.”