Confederate Guerrillas: Effective Commands or Detrimental Service? Part 1

In spring 1863, the American Civil War had waged for nearly two years. In the East, over the course of the previous two years President Abraham Lincoln had desperately hoped for a battlefield victory after numerous commanding generals had failed him and the people of the North.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis, however, left things in the hands of his most trusted subordinate, Robert E. Lee. He had delivered victories and good news to the Confederate cause and government since he took command of the Army of Northern Virginia just a year prior.

Confederate success had not been in sight in the West for quite some time, and winning Union generals with names like Grant, Sherman, and Porter rose to prominence in the media and against their adversaries. This was the military climate across both theaters of war when in early spring 1863, a different approach to the war in Virginia was about to begin.

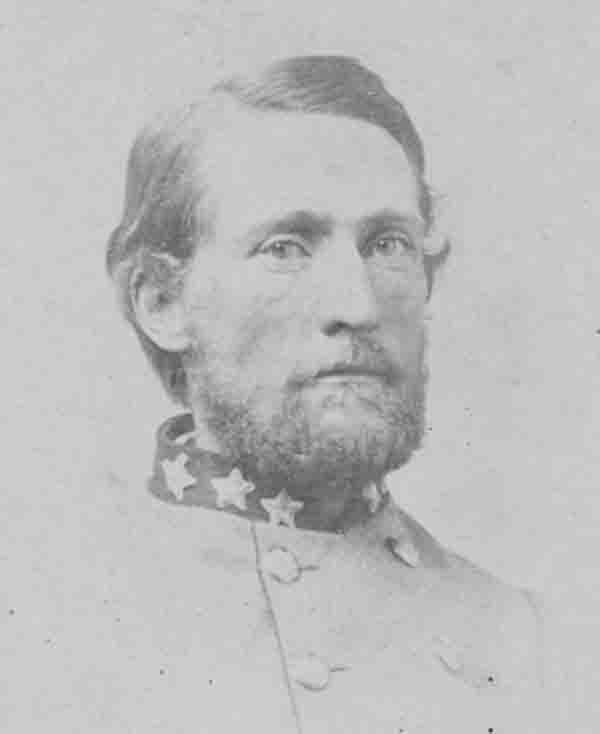

This new Confederate approach, guerrilla-, ranger-, or partisan-style warfare was occurring all through the Confederate states, but for the northern counties of Loudoun and Fauquier in Virginia it had yet to be exploited to its fullest potential. With the blessing of J.E.B. Stuart, John S. Mosby began operations in those two geographic regions of Virginia, soon to be known as “Mosby’s Confederacy.” For the rest of the war, Mosby’s activities in this arena saw its share of triumphs and defeats, but did his operations affect positively or negatively not only the Army of Northern Virginia, but the Union Army of the Potomac? To answer the overall effect of his and his command’s work in that portion of the state, one must first examine the operations themselves and a brief history of the unit.

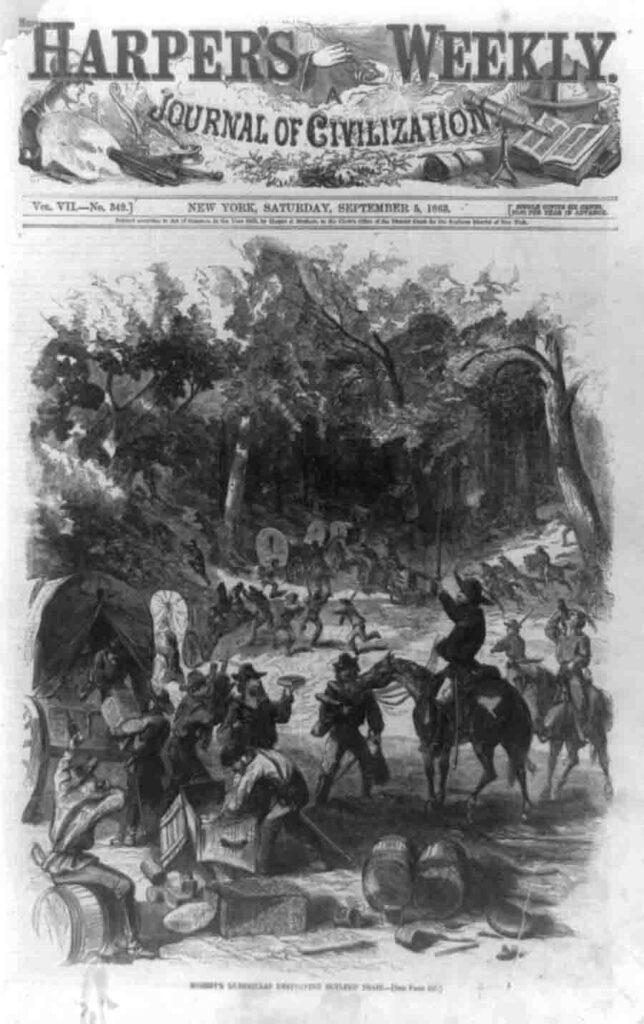

Mosby’s operations started small in this portion of Virginia in the spring of 1863, but it did not remain this way for long. Over the course of the next two years, Mosby and his partisans attacked Yankee troops, wagon trains, railroads, supply depots, rail stations, and communication and telegraph lines. One thing that did not change as these operations and activities blossomed during the later part of the war was Mosby’s command style or responsibility of having a semi-independent command with few officers above him. As Mosby’s fame and accomplishments mounted during the early months, his irregular group transitioned during the war to an official unit with Confederate service as the 43rd Battalion of Virginia Cavalry with continual additions of companies as the command expanded. Before Mosby acquired his “Confederacy,” the hero of Loudon and Fauquier counties had trained with some of the best cavalry officers in the Confederacy, training which aided in him in his future semi-independent command.

Like so many other guerilla partisans, the origins of their military experience began in the official, regular Confederate service, infantry, artillery, and cavalry units. For Mosby, his service began the same way. Joining up in the winter of 1861, Mosby served in Company D, 1st Virginia Cavalry, Capt. William “Grumble” Jones commanding.1 Mosby remained with his unit through the early winter of 1862 into January 1863.

Restless at the thought of winter quarters, Mosby requested of his superior, J.E.B. Stuart, a nine-man detail to stay behind to begin conducting forays into Loudoun County while the rest of the army went into winter quarters. Mosby recalled the early days, “At the time, I had no idea of organizing an independent command….I thought I could make things lively during the winter months.”2 With Stuart’s confidence and trusted consent, Mosby’s operations had their beginnings, operations that continued for the next 28 months.

Not all independent commands began this way, however. Some partisans and guerrillas within the Confederacy were deserters or men who chose not to go to the front lines in either theater of war. Often these bands were ruthless for plunder and did not associate any strategic, tactical planning, or initiative with formal, regular Confederate commands in their sphere of influence.

Mosby and his nine-man detail did not wait long before starting their active operations. One of the first raids and successes for Mosby was the “Stoughton Raid.” This raid not only bagged a high-ranking Union officer, but also provided Mosby with instant celebrity in the Confederacy. In addition, the success of this mission gave, “A sense of vulnerability [that] now pervaded Union camps and headquarters.”3

Not all of Mosby’s future operations focused on the capture of specific officers or commanders, and this success certainly was not the norm for guerrillas and partisans. Mosby, like all other guerrillas in the Confederate states, primarily focused on wagons with supplies, communications, railroads, and depots, and in worse cases, private plunder of civilians. It was here that Mosby’s command began to take a different course than many of those other commands, however.

From his early service with the Virginia Cavalry and the tutelage he received while with that unit, Mosby’s operations were calculated, planned, and scouted. He weighed risk versus reward, and in the later months of 1863 and 1864 respectively, offered his command to work in conjunction with Confederate armies moving through or operating in “his Confederacy.” Few other commands or bands of partisans in the southern states measured-up to these standards set by Mosby, nor would they be successful in maintaining them if they were set. The rarity of these standards, and the level to which these men operated gave the Confederate government great cause not to allow them to continue their activities.

Part 2 can be read here.

1 Jeffery D. Wert, Mosby’s Rangers: From the High Tide of the Confederacy to the Last Days at Appomattox – The Story of the Most Famous command of the Civil War and its Legendary Leader, John S. Mosby (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990), 28.

2 Wert, Mosby’s Rangers, 31, 33.

3 Wert, Mosby’s Rangers, 47.

Part 2 link is broken

Hey Tim, it looks like it’s working now. I think it was showing as broken because Part 2 wasn’t published until today.