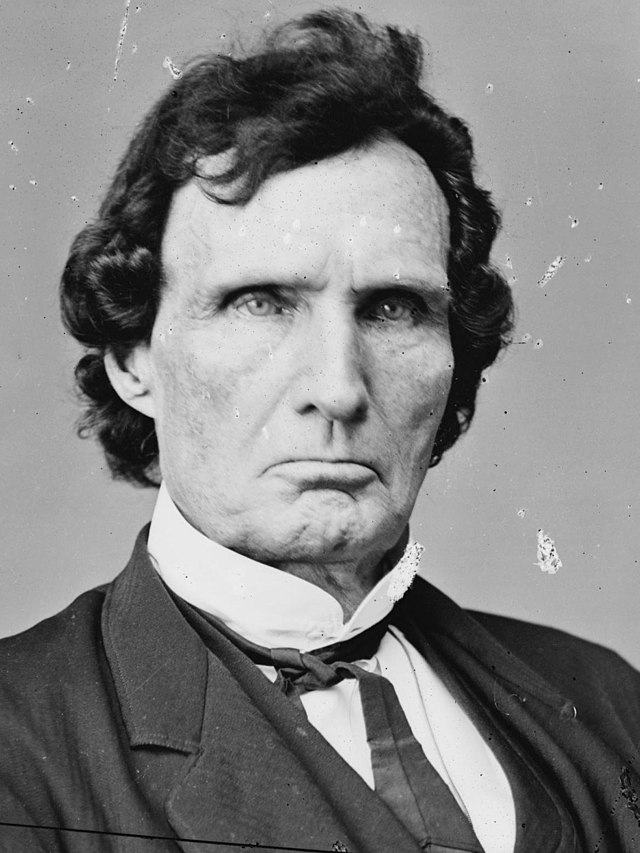

Was Thaddeus Stevens Baptized Into The Catholic Church Just Before His death?

During his career, Thaddeus Stevens was famous as a U.S. Representative for fighting for abolition and harsh war measures during the Civil War. It was during Reconstruction that he rose to his height, becoming highly influential as Congress devised stern measures for dealing with the conquered Confederate states and promoting rights for the formerly enslaved. Stevens was a key figure behind the unsuccessful impeachment of President Andrew Johnson. He died on August 11, 1868, soon after the failure of the impeachment.

The pro-Southern Catholic paper, The Morning Star and Catholic Register, published an obituary on August 30. The paper hadn’t particularly liked Stevens: “Bitter, unyielding, malignant, unscrupulous, unforgiving, this man lived, and humanity breathes a sigh of relief at his death. When the world heard that the great, hard leader was dying, it turned its back upon him as an outlaw from the human family, and its judgment went forth against him. Their universal verdict was: ‘He is lost.'”

Then the paper said: “At the same time God looked down from Heaven upon him, and said: ‘This day thou shalt be with me in Paradise.'”

This curious change of tone came about because, as the paper explained, if accounts of Stevens’ last hours were correct, the previously unbaptized politician had accepted baptism at the hands of one of the nuns who was attending him at his bedside (a priest usually has to administer baptism, but others can do so in an emergency and in the absence of a priest). By Catholic teaching, this meant Stevens had been saved at the last minute, and the Morning Star drew a moral lesson: If Stevens could be saved, who couldn’t be?

The Morning Star proclaimed that “his life was, probably, a prolonged and doubtful struggle against the excessive evil of his nature.” But the provisions of his will showed his affection for his mother. “Was he altogether bad?” the paper asked rhetorically, citing his brutal honesty and even a certain degree of “magnanimity.”

“Who knows the secret history of the man that has thus recently finished the battle of life.? Who knows the warfare he may have waged with his own harsh, stern character, and the evil that he may have often resisted and crushed? If the victory was deferred until the last moment, was it any the less glorious?” the Morning Star asked.

We may need to back up a bit and explain why two nuns were at Stevens’ bedside in his last hours. The nuns in question were Sister Loretto O’Reilly, administrator of Providence Hospital in Washington, and Sister Genevieve, one of the hospital’s directors. Both nuns were white, contrary to some Stevens biographers who reported them as black.

Providence Hospital had been set up on Capitol Hill by the Sisters of Charity, an order of Catholic nuns, to care for patients in a peaceful and calm environment. But this was 1861, so the original plans had to change slightly when the first casualties from Bull Run came to Washington – many casualties were taken in by Providence Hospital. The Sisters, and the hospital’s doctors, took care of wounded soldiers (from both sides) at Providence Hospital. The sisters, as if they weren’t busy enough, also worked at other hospitals in the city. Other than Providence Hospital, all the hospitals in the city were run by the military.

Civilian medical needs, including charity cases, persisted during the war, and Providence Hospital took in some of these patients, helped by Congressional appropriations. Thaddeus Stevens was a key leader in pressing for these appropriations. The hospital got a federal charter in 1864.

The hospital’s care for civilian patients, and the Congressional appropriations, continued after the war. So now we can get some idea of why two top nuns from the hospital were visiting their institution’s dying benefactor.

An August 13 account in the New York Herald said that “to the very minute of his death [Stevens] enjoyed the clearest use of his faculties.” The article also said: “About ten minutes before his death sister Laretta [sic] requested the permission of his friends to perform the religious ceremony of baptism, and no objection being offered the ceremony was performed amid impressive silence, which was rendered more impressive by the stillness of the late hour of the night. At this time his breathing was very much obstructed, and be seemed to suffer from a violent palpitation of the heart, but this passed off, and during five minutes before he breathed his last he lay motionless and quiet as if in a gentle sleep. To her who performed it this act undoubtedly appeared one of great importance, and the earnest and affectionate devotion with which it was done Strangely affected those who witnessed it, even those holding a different faith from hers.”

Other Catholic papers besides the Morning Star weighed in on the question of Stevens’ baptism. The Boston Pilot, which had supported the Union during the war while opposing the emancipation of the slaves, would have had no love for Steven’s “radical” policies. But the Pilot seemed optimistic about Stevens’ spiritual state: “[Stevens] himself did not appear to think his approaching dissolution was near at hand; and it was only an hour or so before his death that Sister Loretto O’Reilly, with his own assent, and that of his cousin and nephew, conferred upon him the rites of baptism. authorized by the Church in extreme cases, when no clergyman is accessible. It is devoutly to be hoped that the soul of the deceased has received the benefit of this holy sacrament.”

The Catholic Telegraph of September 9 said that the Pilot report “settle[d] beyond cavil that Mr. Stevens died a Catholic in the spirit as well as the letter.” The Telegraph, like the Archdiocese of Cincinnati under whose auspices it was published, had been a rare Catholic voice in favor of emancipation during the war, though that did not necessarily mean full support of “Radical Republicans” like Stevens.

Another Catholic paper opined on the baptism issue, and its skepticism about the baptism was reported in many secular newspapers. “Baptism to adults,” the Freeman’s Journal and Catholic Register in New York proclaimed, “is not given on the ground of ‘no objections,’ but on their ‘asking’ of the Catholic Church for ‘faith,’ to lead them to ‘life eternal,’ and professing their desire to be baptized.”

A 1930s biographer of Stevens, Thomas Frederick Woodley, cited this item and added that the “Freemen’s Journal [sic]” was the “official journal” of the Catholic Church. It was in fact an independent publication, albeit quite popular among Catholic readers (at least laypeople and priests, if not necessarily the favorite of the bishops). The editor, James McMaster, had been an active opponent of the Northern war effort. To put it euphemistically, McMaster was not a fan of Stevens.

Stevens had not been baptized previously to his deathbed scene. He was brought up, in an apparent irony, as a Baptist. This meant that his church would not have baptized him as a baby or a child, and it seems that when he grew up, he drifted away from his denomination, perhaps away from Christianity.

But Stevens was willing to invoke religious concepts. In 1865, apparently referring to Roger Taney’s pronouncement that black people had no rights that whites were bound to respect, Stevens referred to “the atrocious sentiment that damned the late chief justice to everlasting fame, and I fear to everlasting fire.”

And the nuns were not the only Catholics he knew. His trusted housekeeper, Lydia Hamilton Smith, was Catholic.

I’m not sure if the proper Church authorities ever decided the baptism issue one way or another.

For Further Reading

Philip A. Caulfield, “History of Providence Hospital, 1861-1961,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., 1960/1962, Vol. 60/62, (1960/1962), pp. 231-249.

Heritage: Honoring our Hospitals’ Early Years in the Nation’s Capital. Washington: District of Columbia Hospital Association, 2015.

Timothy S. Huebner, “‘The Unjust Judge’: Roger B. Taney, the Slave Power, and the Meaning of Emancipation.” Journal of Supreme Court History, Volume 40, issue 3 (2015), pp. 249-262.

William B. Kurtz, Excommunicated from the Union: How the Civil War Created a Separate Catholic America. New York: Fordham University Press, 2016.

Bruce C. Levine, Thaddeus Stevens: Civil War Revolutionary, Fighter for Racial Justice. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2021.

Max Longley, For the Union and the Catholic Church: Four Converts in the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015.

Max Longley, “The Radicalization of James McMaster,” U. S. Catholic Historian, Vol. 36, No. 4 (Fall 2018).

Sister Anthony Scally, “Two Nuns and Old Thad Stevens,” Biography, Volume 5, Number 1, Winter 1982, pp. 66-73.

Hans L. Trefousse, Thaddeus Stevens: Nineteenth-Century Egalitarian. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001.

Francis R. Walsh, “The Boston Pilot Reports the Civil War,” Historical Journal of Massachusetts, June 1, 1981.

I shared your interesting post with the head of the Thaddeus Stevens Society in Gettysburg.