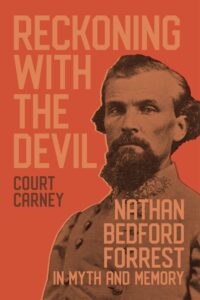

Book Review: Reckoning with the Devil: Nathan Bedford Forrest in Myth and Memory

Reckoning with the Devil: Nathan Bedford Forrest in Myth and Memory. By Court Carney. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University 2024. Hardcover, 213 pp. $44.95.

Reviewed by Brian Steel Wills

Confederate cavalryman Nathan Bedford Forrest generated numerous controversies in his own time and since, buttressed by a powerful reputation as a warrior/general that various entities have incorporated for their purposes and symbolized ultimately by an equestrian statue that stood in a park named after him in Memphis, Tennessee. Even so, the term “controversial” when applied to him has also come into question. Some feel that Forrest was an extraordinarily gifted military practitioner, accomplishing feats of arms often against superior odds. Many of these individuals have felt that his military career and successes trump all other aspects of his life.

Others condemn Bedford Forrest as evil incarnate and guilty of the most heinous activities throughout his lifetime. They see a man, at best symbolic of the scourge of slavery that wracked the region and the nation, a soldier whose unbridled bloodlust showed no mercy and a less than recalcitrant figure in defeat who refocused his racist hatreds on newly freed peoples through a vile secretive institution. Of course, the Forrest of whom both camps have written was a complex personality and a product of the times in which he lived.

Court Carney attempts to grapple with this Forrest phenomenon, delving into specific periods associated with his life and legacy. As Carney maintains, in the years after the cavalryman’s death, adherents to the general won the initial battle for the soul of Memphis, a city not yet in a position to confront its corporate demons. Then in a haze of “Lost Cause” memorialization and gentle, if not genteel, examinations that focused almost entirely on the military story, Bedford Forrest’s persona grew, even as his shadow blotted out other elements of the city, its diverse population, and its collective history. Only as progress occurred in other locales, in the modern era, carried on the momentum of repulsion at racism and violence, could the city and its citizens at last purge themselves of the tainted past that the Confederate and his compatriots represented, by removing the memorials to the general. A reckoning had finally come to the devil in gray.

Again, the story is more complicated than this volume suggests. At the end of the conflict, Union generals such as William T. Sherman expected Forrest to continue to wage war, even as larger formal armies surrendered. Instead, he accepted the outcome of the war and went home to rebuild. Part of this effort involved paving Memphis streets and lending his name to insurance and railroad enterprises, which the author essentially ignores.

After the Civil War, a Freedmen’s Bureau report noted that Forrest offered former slaves higher contracts than other planters were willing to give. This was typical of Forrest, who acted in that case not for humanitarian purposes, but because he knew that this was the means by which he could secure those workers for himself.

Yet, Nathan Bedford Forrest, the pre-war slave trader, commander of the troops who attacked Fort Pillow in April 1864, and first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, could not escape these elements of his life. He understood the position this gave him to many detractors but remained unapologetic. As such, the 1905 statue served, in the author’s estimation as “a kaleidoscopic avatar of Memphis,” which radiated “variegated flashes of history and myth, folklore and dishonesty.” (48) This memorialization of the Confederate Forrest was just the first of a series of “palimpsests” (174) or rewritings of the story until the 1905 statue (and another outside the city) came down.

Throughout the course of his examination, Carney’s approach leans heavily toward dismissiveness regarding any efforts to contextualize Forrest less negatively. He questions the stances of previous Forrest historians and biographers, particularly more recently the colorful personality Shelby Foote. Most fascinating is the author’s latter focus on a salacious and provocative novel and warped wartime Union newspaper editorials. Forrest’s mother, wife, and even the young Emma Sansom of Gadsden fame, come under a lens that questions the Confederate’s morality and his relationship to women. There are many dark corners of Forrest’s life that not a few biographers and historians have already shed light upon, but the evidence is scant and flimsy that miscegenation was one of them.

There is no need to look for objective balance here, although buried in the notes is a quote from historian Doug Cupples that would have been a much better method for assessing Forrest and his memorialization without supporting him or condemning him outright. (191n47) Indeed, this would have been a more useful approach to understanding and assessing the legacy of the Confederate and his statue and its removal for the author to employ.

Brian Steel Wills is Professor of History Emeritus at Kennesaw State University and the university’s former Director of the Center for the Study of the Civil War Era in Kennesaw, GA. In addition to leading tours, offering lectures, and conducting programs, Dr. Wills is the award-winning author of many books relating to the Civil War, including biographies of Confederate generals Nathan Bedford Forrest and William Dorsey Pender, and Union General George Henry Thomas. Brian has also written about the Civil War in the movies and recently published a study on noncombat deaths in the Civil War. He is a graduate of the University of Richmond, Virginia, and the University of Georgia.

A fair and nonpartisan review. One other facet of Forrest’s life often neglected by historians is his conversion to Christianity after the Civil War. Most just demonize Forrest and ignore the positive changes he made during his post war life. They get so involved with supporting the Confederate Lost Cause myth they refuse to acknowledge the Federal Righteousness myth.

I’ve come to accept that “controversial” and “problematic” figures from this era are merely easy templates and targets for many modern writers. Ironically, their approach to objective history is no different than that of the most zealous of the Lost Cause advocates they pretend to excoriate.

Excellent review of a book intended not as a scholarly work but to ride the popular wave that was the cancel culture war.

Amen, y’all. Read Carney’s bio: he would be better off sticking to Bob Dylan and jazz.

Excellent as usual, Wills! I’ve seen the sex slaves accusation elsewhere, at it seems unlikely.