The 1811 Slave Revolt Trail and Destrehan Plantation

While visiting historic Destrehan Plantation outside New Orleans, I came across a sign for a fascinating history trail the focused on an 1811 slave revolt in the area.

While visiting historic Destrehan Plantation outside New Orleans, I came across a sign for a fascinating history trail the focused on an 1811 slave revolt in the area.

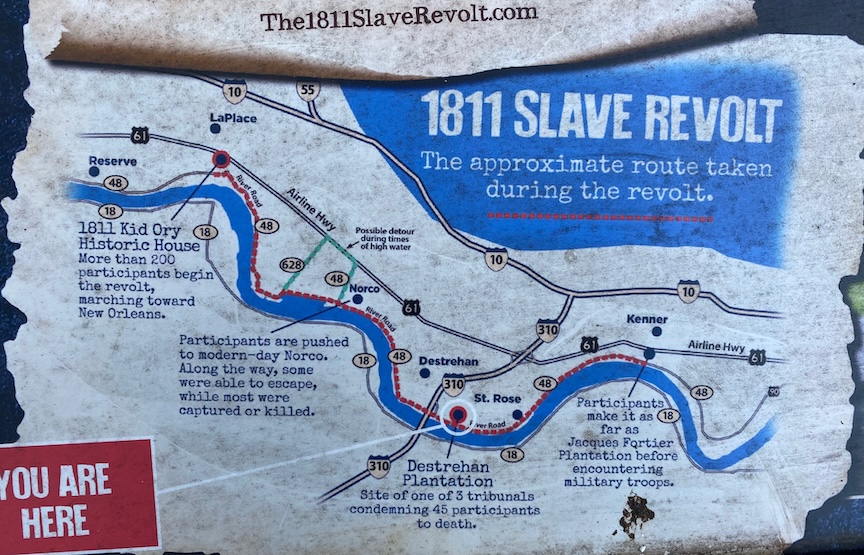

On January 8, 1811, as many as 500 enslaved men and women engaged in a two-day uprising that had far-reaching implications. The group marched toward New Orleans, burning buildings along the way and killing two plantation owners. The revolt was soon repressed, and public executions followed.

You can read a short overview of events at The1811SlaveRevolt.com, which also provides information about the trail. According to the website:

The 1811 Slave Revolt Trail follows closely the pathway the original participants took on their journey toward freedom. Follow in their footsteps on bicycle or foot along the current levee pathway, or follow along on the Great River Road. The route will take you on an approximately ten-mile trek between the 1811 Kid Ory Historic House in LaPlace and Destrehan Plantation in Destrehan (slightly longer via car, and if high-water detours are needed). The trail will take you across the Bonnet Carre Spillway and several small towns along the way.

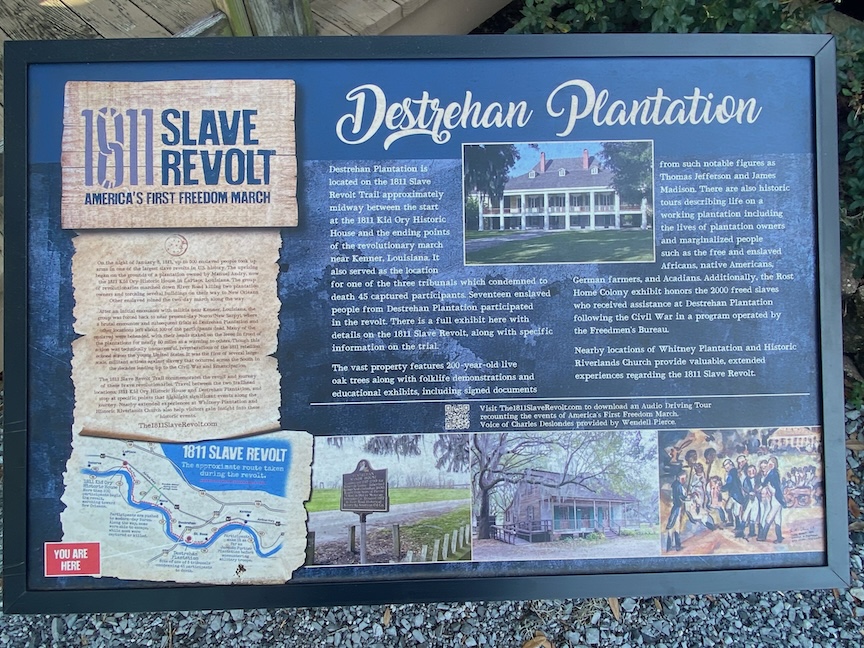

I wasn’t able to visit the Kid Ory Historic House, but Destrehan Plantation was fascinating. Interpretation offered the full story of the plantation, including the lives of the people who lived in the house and the enslaved people who worked the grounds. Rather than present a white-washed view of slavery, the site dealt with it fully and honestly—good, bad, ugly, and rebellious—which deepened my understanding of the plantation’s entire history.

The main house itself was grand and well preserved, with rooms restored to tell the stories of residents at different eras over the house’s long life. A climate-controlled museum space showed off a number of key artifacts and documents, including a rare portrait of Thomas Jefferson, and exhibits showed off the extraordinary craftsmanship of the building’s carpentry.

A small cluster of buildings behind the main house provided a glimpse into the lives of the enslaved population that operated the plantation, and another museum space displayed artifacts that helped tell the stories of those people. A list of their names, which any known basic biographical information, is mounted on the front porch of one of the buildings as a kind of witness to people who might otherwise be forgotten or overlooked by history.

The grounds were beautiful, too, and a number of ancient live oaks, which bore witness to events at Destreham, still stand like noble stewards, thick with beards of Spanish moss.

I wasn’t sure what to expect when I arrived, but I was really pleased with my experience at Destrehan Plantation and highly recommend it to anyone interested in Antebellum history.

I apologize that I did not have the chance to walk around to the front of the main house and grab any pictures. I was tour leader that day and busy herding curious cats.

I apologize that I did not have the chance to walk around to the front of the main house and grab any pictures. I was tour leader that day and busy herding curious cats.

Always interesting to see how America reacts to revolts. The 1811 revolt led to the execution of many of the insurgents. The 1861 revolt did not. The difference might be attributable to the color of the rebels.

I’ve been thinking about that a lot lately in terms of Nat Turner and his rebellion. How did that event differ in spirit and in action from colonists in Boston in the 1770s? I am not suggesting they are equivalent–they are not–but their similarities and differences are worth thinking about. And then how are those rebellions similar and different from Secession? If the animating spirit is a rebellion against unjust authority and the legitimacy of violence in the pursuit of those goals, then there’s suddenly a lot of gray area to look at–and the question of “black” and “white” becomes all the more stark.

And quantity…although the alleged comment by Thadeus Stephens about hanging every white southern male might have solved a lot of probelms since 1865, I believe it would have been difficult to carry out. Lunching requires a lot of spectators/perpetrators and few victims.

My wife Brittany went to school just a short distance from where soldiers fired into the enslaved people. Her dad works right where that happened. Each semester, I make it a point to show my students the paintings that are on display at Destrehan. They make this event, and the consequences, so real for students.

“To New Orleans” in the one graphic, as if the ill-fated revolutionaries could read or needed directions. At one Symposium I had a someone say to me that “slaves were property like a nice car. You wouldn’t mistreat your expensive car, would you.” I replied that you wouldn’t want your car driving itself off the plantation, and that slaves were commonly whipped to keep them in line and aware of the consequences. It takes alot of mistreatment and abuse for 500 people to take these actions of this article. I’m reading Freemantle’s “Three Months in The South.” So far into it, what a tool he is on slavery.

A good book about this too often overlooked but highly significant event is “American Uprising: The Untold Story of America’s Largest Slave Revolt” by Daniel Rasmussen.