Faces of Tarheel Irish Soldiers: Faugh a Ballagh!

The Confederacy had no official “Irish” brigade, like the Army of the Potomac’s infamous Irish Brigade, but historians know the South mustered in thousands of Celts: Irish, Scottish, and Welsh. I thought I’d use my book series format called, Faces of… and introduce five of those Irish or semi-Irish for St. Paddy’s Day. All of these soldiers were from North Carolina and fought in the infantry or cavalry with the Army of Northern Virginia. [1]

Captain George Burns Bullock enlisted at age 22 in Granville County, April 1861; he surrendered with his regiment at Appomattox, Virginia April 1865.

Bullock grew up in Warren County on his family’s plantation, but enlisted in the next county over, Granville. His enlistment papers state he was a student. He first mustered in with the 12th NC and served as a sergeant. He came down with typhoid fever in July 1862. He survived and was then elected lieutenant in Co. I, 23rd NC Regiment.

At Chancellorsville, he was captured May 3, 1863, but was exchanged later that same month. He rejoined his regiment just in time for the Gettysburg Campaign.

He led his men at the horrific site known as Forney’s field, July 1, 1863. He later described the slaughter of his regiment and entire brigade. The “blood ran like a branch. And that too, on the hot, parched ground.” The brigade suffered 900 casualties out of 1,400 men. Of the approximate 300 officers and men in the 23rd NC, Lt. Bullock and about twenty enlisted men came out unscathed. Total casualties were around 283 rank and file, 84.2%. Bullock’s subsequent promotion to captain was dated from July 1.[2]

Captain Bullock escaped physical injury in subsequent battles of 1864 and 1865, e.g. Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Bethesda Church, Cold Harbor, 3rd Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, and Belle Grove.[3]

He returned home in 1865. He died April 21, 1891, and is buried in St. John’s Episcopal Churchyard, Williamsboro, Vance County, North Carolina.[4]

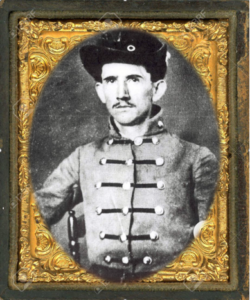

Co. I, “Duplin County Rebs”, 9th Reg. NC State Troop (also known as 1st Reg. NC Cav.)

Sergeant William B. Kennedy enlisted at age 24 in 1861. He died on December 29, 1864.[5]

Kennedy died at General Hospital, Number One, Kittrell Springs in the former Kittrell Springs Hotel.[6] Details of why he was there aren’t available. His regiment, however, was involved in a skirmish on December 8, 1864. He may have been wounded and died several weeks later.

The skirmish occurred around the Petersburg & Weldon Railroad. Union Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren attacked at the village of Belfield. “Here, the Junior and Senior Reserves of North Carolina and Virginia made an admirable defense of the bridge until the infantry and cavalry came up, when the enemy was forced to retire. The main pursuit was made by my brigade, and especially the 9th NC Regiment, two squadrons of which, under Capt. George S. Dewey, making a splendid mounted charge.” The loss in the regiment included 138 killed, wounded, or missing.[7] Kennedy is buried in Kittrell Confederate Cemetery, Kittrell, Vance County, North Carolina.[8]

Co. H, “Caswell Boys,” 6th NC Regiment

Sergeant Bartlett Yancey Malone enlisted at age 22 on June 6, 1861.

Malone grew up in Hyco Creek community in southeastern Caswell County. Although not well educated, he kept a diary. It was later developed into a book called: Whipt’ em Everytime: The Diary of Bartlett Yancey Malone, Co. H, 6th N.C. Regiment.

The 6th fought in all the major battles in the northeast theater, starting with 1st Manassas, July 21, 1861. Malone, however, doesn’t discuss the combat in detail. He writes about it in passing, like he was an observer. The “…first day of July 1862 I was in the fight of [Malvern] Hill And the first day of July 1863 I was in the fight at [Gettysburg]…”[9] That’s all the reference we get of those battles. It’s not uncommon.[10] What does he mostly recall? He gives us a daily weather report as a soldier. Diaries seemed to have a lot of weather.

The diary takes a more interesting turn when Malone was captured and sent to Point Lookout (Camp Hoffman), Maryland, in November 7, 1864. I was surprised to learn that colored troops guarded prisoners, even shot some for “no cause,” according to Bartlett. We don’t get the whole story of course.[11] I didn’t think the Union army allowed U.S. Colored troops near the Southern prisoners, so I learned something new.[12] Malone was furloughed March 2, 1865. The diary ends at this point.

Bartlett Yancey Malone returned home. He died May 4, 1890, and is buried in Lynches Creek Primitive Baptist Church Cemetery, Corbett, Caswell County.[13]

Co. H, 55th NC Regiment

Captain Edward Fletcher Satterfield enlisted at the age of 24 in early spring 1861.[14]

Satterfield is one of the best known North Carolinians, especially among students of the battle of Gettysburg. He grew up in Roxboro, Person County, North Carolina. Prior to the war, he studied law at the University of North Carolina and was a lawyer in his hometown.

He first served as a lieutenant in Co. A, 24th NC Regiment. On Oct. 19, 1862, he joined Co. H of the 55th. He was promoted to captain March 10, 1863.[15]

The 55th’s first large-scale battle was at Gettysburg. On July 1, 1863, the regiment fought in the morning battle on McPherson’s Ridge and the infamous railroad cut. The North Carolinians got chewed up pretty bad. Despite this, the regiment was called upon again for the final assault (aka Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble charge) on July 3. The 55th was led by Capt. Gilreath. Satterfield took up position with his depleted company. He and a few others made it to the Bryan barn on Cemetery Ridge. Capt. Satterfield and a handful of North Carolinians pushed forward in one last effort to reach the Union line. The 2nd New Jersey met them with a hail of buck-and-ball only nine yards away. The blast tore Satterfield’s body into fragments. Edward Satterfield was 26. His remains were never identified.

He is buried in a Confederate grave of unknown soldiers either at Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia or Oakwood Cemetery, Raleigh, NC

Out of 640 soldiers, the 55th lost 39 killed, 245 wounded, and 55 missing or captured, thirty-one percent at Gettysburg.[16] Capt. Gilreath was among those killed during the final assault.

Co. K, 20th NC Regiment

Corporal Bradley Flowers Yates Jr. enlisted at the age of 16 on October 3, 1861.[17]

Yates grew up in a farming family in Columbus County, North Carolina. He and his three older brothers joined at Fort Johnson, Smithville (now Southport). The regiment was first assigned to guard Smithville, Fort Caswell, and Wilmington until June 1862. At this point, the regiment was sent north and joined the Army of Northern Virginia on the Virginia peninsula. The 20th’s baptism by fire was at the Seven Days Campaign. His older brother, Sgt. (Doctor) Elmore Yates, was seriously wounded in the hip at Malvern Hill, July 1, 1862. He died July 23.[18]

At the battle of Sharpsburg, the 20th saw action in the bloody lane on September 17, 1862. Bradley and his two older brothers, James and John, escaped the carnage. The war finally caught up to Bradley and John at Gettysburg. On July 1, 1863, their regiment was part of Iverson’s brigade. The entire North Carolina brigade was ambushed in Forney’s field near McPherson’s Ridge. Bradley’s right arm was mangled. He still held onto the regimental colors when Union troops found him alive. Bradley and John were captured along with most of what remained of their brigade. John died of epilepsy while a prisoner in 1863.[19] James E. Yates died in November 1863. Bradley had his arm amputated and was exchanged September 16, 1863.

He was given a medical discharge and returned home. Bradley Flowers Yates, Jr. married Ellen Maria Williams. The two had seven children. Bradley died in 1899 and is buried in Piney Forest Baptist Church Cemetery, Lot 64, Chadbourn, Columbus County.[20]

[1] I chose this state because it’s my home now. Some individuals I selected had surnames with a definite Irish connection. Other surnames didn’t immediately sound Gaelic so I checked to see if their surnames had some background. I didn’t do a deep dive into ancestry.com.

[2] http://www.gdg.org/research/OOB/Confederate/July1-3/iverbgd.html. I’m not a big fan of court martialing unless a blatant crime has been committed. I’d make an exception in the case of Brig. Gen. Robert Iverson’s performance on July 1, 1863. I wouldn’t put him up on charges for possibly being drunk, but rather, his failure to put out skirmishers. Putting skirmishers out is tactical training 101. Captain Vines E. Turner in his history of the 23rd NC Regiment, described this whole dismal affair: “unwarned, unled as a brigade, went forward Iverson’s deserted band to its doom. Deep and long must the desolate homes and orphan children of North Carolina rue the rashness of that hour.” Ibid. For casualties in Iverson’s brigade, see https://gettysburgcompiler.org/2018/07/18/iversons-assault-a-cautionary-tale/.

[3] https://www.carolana.com/NC/Civil_War/nc_officers_in_csa_captains.htm and https://tarheelfaces.omeka.net/items/show/47. Other battles he participated in include: Mine Run Campaign, 1st Hagerstown, Raccoon Ford & Stevensburg, Bristoe Campaign, Lynchburg, Monocacy Junction, Snicker’s Gap, Stephenson’s Depot, 2nd Kernstown.

[4] https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2343602/saint-john’s-episcopal-churchyard?

[5] https://ncgenweb.us/duplin/records/military/duplin-county-rebels. Photograph found at https://www.pinterest.com/pin/3096293478954970/. There’s an interesting discussion about his uniform on Civil War Talk. He has a “U.S.” belt buckle and yellow sergeant chevrons. https://civilwartalk.com/threads/thoughts-on-dismounted-cavalry.161359/page-4. Most Confederates didn’t wear formal uniforms. The average Confederate wore civilian clothes.

[6] Kittrell Confederate Cemetery, Hospital to Graveyard. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=222000.

[7] https://www.carolana.com/NC/Civil_War/9th_nc_regiment.html.

[8] https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/47150/kittrell-confederate-cemetery?

[9] https://archive.org/details/diaryofbartlettymalo/page/30/mode/2up, 49.

[10] He most likely wasn’t ready to process what he had seen and done—the gore and trauma and chaos of battle, or he didn’t want to talk about it. If you look through Civil War diaries, you’ll find many recorded the weather. Memoirs are different. These are written fifteen to thirty years after the events. That’s usually the timeframe a soldier is emotionally ready to discuss combat trauma. There are exceptions in military history. The English soldiers, Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, wrote powerful poetry while serving in the trenches during WWI.

[11] https://archive.org/details/diaryofbartlettymalo/page/52/mode/2up?q=Malvin, 52.

[12] I had to fact check Malone because having colored troops guard Southern prisoners seems like one of those bad military experiments. Yep, the U.S. military allowed it, and there were problems. Further reading, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2017/03/08/the-reminiscences-of-a-union-prison-guard/

[13] https://sites.rootsweb.com/~ncccha/memoranda/civilwar/civilwar.html. Edward Alexander goes over Malone’s diary in his blog at https://emergingcivilwar.com/2018/04/20/whipt-em-everytime-the-poorly-titled-diary-of-bartlett-yancey-malone/#:~:text=Bartlett%20Yancey%20Malone%20was%20born,the%20rolls%20through%20March%201865. For more on 6th NC Inf., see Walter Clark, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Histories_of_the_Several_Regiments_and_B/IsymTHPo65gC?hl=en&gbpv=1.

[14] 55th NC Regiment had nine companies and a wide-range of counties represented: Company A – Wilson County; Company B – Wilkes County; Company C – Cleveland County; Company E – Pitt County; Company F – Cleveland, Burke, and Catawba Counties; Company G – Johnston County; Company H – Alexander and Onslow Counties; Company I – Franklin County; and Company K – Granville County.

[15] During the Chancellorsville Campaign, the 55th was with Lt. Gen. James Longstreet in Suffolk, VA.

[16] This five minute video was very helpful. It’s produced by the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, PA. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fwgib2qp6tw. For further reading on the 55th’s fight on July 1, 1863 see Kristopher D. White’s blog at https://emergingcivilwar.com/2015/04/20/the-bloody-railroad-cut-at-gettysburg-part-one and Fight Like the Devil: The First Day at Gettysburg, July 1, 1863, by Chris Mackowski, Kristopher D. White, and Daniel T. Davis. For a regimental history see Walter Clark, History of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina, vol. 3. For a short biography on Satterfield see https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/27452653/edward-fletcher-satterfield.

[17] Photograph courtesy of Mrs. Karen Freeman. see https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/31947791/bradley-flowers-yates. The 20th Regiment was made up of men from several counties: Brunswick, Columbus, Cabarrus, Duplin, and Sampson.

[18] Elmore is buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, VA. See Find a Grave https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/130843692/doctor_elmore-yates and Roster of North Carolina Troops, vol. 2, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Roster_of_North_Carolina_Troops_in_the_W/VhATAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&kptab=editions&gbpv=1&bsq=Yates

[19] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/20089860/john_w-yates.

[20] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/31947791/bradley-flowers-yates. See also https://npsgnmp.wordpress.com/2012/12/28/prisoners-part-3-a-confederate-story/.

Excellent, engaging piece. Thank you. And thanks for the You Tube link on Captain Satterfield. When I visit Oak Ride and look out over the purported “Iverson pits,” I feel uneasy to reflect on what happened on what now appears peaceful pasture land. That Captain Bulloch survived Forney’s Field and other horrendous battles is incredible

My Great Great Grandfather Andrew McGee served in the 55th company H he survived