“Try to think what we are going to do ourselves”: Grant at the Wilderness and Shiloh

One of my favorite comments from Ulysses S. Grant comes near the end of the second day of the battle the Wilderness. It resonated with me in a strange way today on the anniversary of the battle of Shiloh, which took place two years earlier than the Wilderness and more than 700 miles away.

One of my favorite comments from Ulysses S. Grant comes near the end of the second day of the battle the Wilderness. It resonated with me in a strange way today on the anniversary of the battle of Shiloh, which took place two years earlier than the Wilderness and more than 700 miles away.

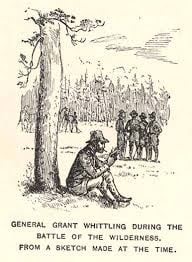

On May 6, 1864, Confederate Second Corps division commander Maj. Gen. John Brown Gordon launched a late-day attack against the Federal right flank, and it sent portions of the Army of the Potomac’s command into a tizzy. Grant looked on, bemused, as a staff officer came to him in a panic.

“General Grant, this is a crisis that cannot be looked upon too seriously,” the officer proclaimed. “I know Lee’s methods well by past experience; he will throw his whole army between us and the Rapidan, and cut us off completely from our communications.”

According to Grant aide Horace Porter:

The general rose to his feet, took his cigar out of his mouth, turned to the officer, and replied, with a degree of animation which he seldom manifested: “Oh, I am heartily tired of hearing about what Lee is going to do. Some of you always seem to think he is suddenly going to turn a double somersault, and land in our rear and on both of our flanks at the same time. Go back to your command, and try to think what we are going to do ourselves, instead of what Lee is going to do.”

I’ve always loved this comment from Grant because it demonstrates his offensive-mindedness. He wanted to focus on his own plans and executing them as successfully as possible. He did not want to surrender the initiative. He would not let worry cripple him into inaction. This had been a key feature of the Army of the Potomac and the deep-rooted cautious conservativism that became known as “McClellanism” after its one-time commander, George B. McClellan.

In a way, I’ve even used Grant’s comment as a philosophy for managing Emerging Civil War over the years: Let’s focus on keeping our own house in order, and let’s not worry what the other guys are doing. Let’s just do what we do as well as we’re able. Concentrate on “us.”

However, there is a drawback to Grant’s single-minded focus on “what we are going to do ourselves” without consideration of what the enemy might do. For an illustration, we can look back at Shiloh.

On the morning of April 6, 1862, Albert Sidney Johnston’s army surprised Grant near Pittsburg Landing. Because of the area’s tumultuous terrain, Grant’s had not ordered his army to fortify its position. “When all reinforcements should have arrived I expected to take the initiative by marching on Corinth, and had no expectation of needing fortifications,” he admitted. Another reason came from his engineer, Col. James B. McPherson, who had scoped out the area and expressed a concern than any new position could not “easily be supplied with water.”

“The fact is,” Grant explained in his memoirs, “I regarded the campaign we were engaged in as an offensive one and had no idea that the enemy would leave strong entrenchments to take the initiative when he knew he would be attacked where he was if he remained [in Corinth, Mississippi].”

By focusing too much on what he was up to, he neglected to take into account what the enemy might do to him. Grant could generally take the measure of an opponent, but he perhaps neglected to consider the desperate straits Confederates were in at that particular moment in the war, strategically. After the twin defeats of Forts Henry and Donelson and the loss of most of western and central Tennessee as a result, Johnston needed a game-changer, and he thought an attack on Grant’s army would provide that opportunity.

I typically give Grant credit for being a quick learner on the battlefield—it’s one of his most underappreciated traits—but Shiloh represents an instance where he failed to learn his lesson. After all, at Fort Donelson, Confederates had also sprung a surprise attack on him while he was busy making offensive plans?

Grant had excused himself from the Donelson front to confer with an injured Andrew Foote, anchored upriver and unable to leave his boat. Grant was so confident that the Confederates would stay bottled up in the fort that he didn’t even assign anyone to in charge in his absence. Perhaps that was a reasonable assumption considering the demonstrated meekness of the garrison’s most experience military, commander Gideon Pillow. “I had known General Pillow in Mexico, and judged that with any force, no matter how small I could march up to within gunshot of any intrenchments he was given to hold,” Grant later said. “I knew that [John B.] Floyd was also in command, but he was no soldier. . . .” Grant also knew the strength of Fort Donelson’s impressive defenses.

Grant rushed on to the scene outside Donelson in time to make order from chaos, just as he did at Shiloh. One of his first orders of business in both instances was to order ammunition to the front—a reflection of his offensive mindedness (and his experience as a former quartermaster). Key pauses by Confederate leaders at Donelson and Shiloh also gave Grant the opportunity to regroup and seize the initiative. “Some of our men are pretty badly demoralized, but the enemy must be more so . . .” Grant realized at Donelson. “[T]he one who attacks first now will be victorious. . . .” At Shiloh, he resolved to “attack at daylight and whip them.”

We might also make an argument that Grant’s advance into Mississippi in December 1862 came to grief because he was too focused on moving forward and not attentive enough to the situation in his rear. Twin hits on his supply line by Nathan Bedford Forrest in Jackson, Tennessee, and Earl Van Dorn at Holly Springs, Mississippi, crippled his ability to advance on Vicksburg via an overland route. I’m less inclined to criticize Grant’s mindset in these cases because operations like that are always a delicate balancing act between having enough men to protect your supply route and having enough men to conduct operations. (This was William S. Rosecrans’s calculus in the early half of 1863, for instance.)

As the old saying goes, “Life is what happens while you’re busy making other plans.” In Grant’s case, Confederate attacks happened while he was busy making other plans. To his credit, he eventually learned this lesson and did more to protect himself and his army as he planned “what we are going to do ourselves”: Don’t panic, and stick with the plan.

His comment, of course, is perfect for these troublous times.

That is one of the things I most like about Grant. He was always able to stay calm in difficult circumstances regardless of who (himself or otherwise) caused them. You fight a war over 4+ plus years and bad things are eventually going to happen. His countenance allowed him the ability to learn from unfavourable outcomes rather than fold or quit.

He carried that demeanor all through life, too. He held his composure when Ferdinand Ward broke the news of Grant & Ward’s financial trouble, for instance.

And within a few hours Lee outthought Grant yet again, and got Richard Anderson moving the First Corps down the road to Spotsylvania, once again blocking Grant on the road to Richmond – which, by the way, he never did manage to capture. Looks like nobody, neither Grant nor his generals, did much thinking about what they would do to Lee.

Anderson’s move to Spotsy was one of the great lucky breaks of the war. Lee sent Anderson to Spotsy as insurance, not because he knew Grant was going there. The idea was to send Anderson to Spotsy and, from there, probably toward Fredericksburg or the Telegraph Road, all on the assumption that Grant was going to pivot to Fredericksburg. The decision proved fortuitous considering Grant’s decision to move to Spotsy. But had the Confederate cavalry not delayed Grant’s advance, Grant would certainly have reached Spotsy first and force Anderson to either attack or shift further west and south.

I know a great book on the topic…. 😉

Good post. I have decided the reason Grant, Sherman, and Prentiss were so blind about the Rebels varied from man to man, but one general sentiment was overconfidence. Fort Donelson was an utter disaster, but the defeats at Mill Springs and Fort Henry were quite embarrassing defeats. Along with Pea Ridge, the general feeling was the Rebellion was played out. Also, news from Virginia was encouraging, where McClellan had started his offensive. That overconfidence extended after Shiloh, by the way and was not truly shaken off until the Confederate counter-offensives.

Thanks, Sean. I think people forget how high on McClellan Grant was early in the war.

“It rains on the enemy, too.” He didn’t originate it but a favorite Grantism for me.

The ironic part of Grant’s Wilderness outburst is that, as I recall, Lee did in fact manage to hit both of Grant’s flanks on that very day (whether Lee “turned a double somersault” while doing so remains in dispute).

Lee did, indeed, hit on both fronts in the Wilderness–and had Gordon’s flank attack come earlier, it might spelled real trouble for Grant, who was focused on the Brock Road/Plank Road intersection. (I would argue that the Plank Road attack was really just straight-up-the-middle for Lee rather than a true flank attack, although Mahone had a mini-flank attack to dislodge part of the Federal defense along the road.)