Tales from a Monk in the Union Army: Lee’s Surrender

As bells echoed in the new year of 1865, the Confederacy’s death knell rang with them. Nearly four bloody years of war exhausted the South, its resources, and its people—and Brother Bonaventure Gaul had, unwillingly, participated in almost half of it. Since the summer of 1863, he and his regiment, the 61st Pennsylvania, fought desperately through the Overland Campaign, settled in for the Siege of Petersburg, followed Gen. Phillip Sheridan’s army into the Shenandoah Valley, and now marched back to Petersburg for the final offensive. As the spring slaughter began in March 1865, Gaul travelled between the reserve hospital near army headquarters at City Point, Virginia, and the division hospital near the front lines.[1]

Gaul experienced his true test of soldiership during the last few years of his service, he was wholly unprepared for the spring campaign. Even as a hospital orderly the monk was ordered to work “with pick and shovel” in the Union army’s desperate attempt to outmaneuver Gen. Robert E. Lee and the Confederates. Despite debilitating back pains, the thirty-five-year-old monk had “to dig trenches 12 to 15 feet deep in mud and rain.”[2] After nearly ten months of a prolonged siege, the land around Petersburg changed dramatically from a peaceful countryside to a scarred hellscape. “If you would just see the large fortifications on both sides, it jolts one dreadfully,” Gaul recalled. “Our Picket post is as distant from the rebel post as is the blockhouse from the bakery. They can easily speak with one another. They often shoot at one another to pass the time, or out of hatred.” Whether Gaul knew it or not, he was participating in the one of the most dramatic epochs in American history—the final act of the Civil War. “Our whole front line is under marching orders,” he penned his friend Br. Ildephonse Hoffmann on March 15, 1865. “We await at any hour a battle of several days. May God grant that the war end soon.”[3]

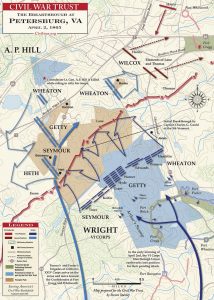

On April 1, 1865, Gen. Grant made final preparations to break the siege. That evening, 150 Union cannons opened fire on the Rebel works around Petersburg. Gaul heard the percussive cannonade from his post and remembered that “the earth shook terribly.”[4] At 4:30 a.m. the next morning, the 61st Pennsylvania and the entire Sixth Corps charged the Confederate trenches. Union troops pierced a hole in the Confederate line, into which the Pennsylvanians stormed.[5] Having finally achieved a breakthrough, the Federal army forced the Rebels to abandon Petersburg and their capital, Richmond. “They fled like sheep, right where General Lee had his headquarters. Fifteen minutes earlier, he would have come into our hands,” Gaul wrote of the Confederate general.[6]

While a detachment of Federal troops marched to Richmond to seize the capital, Grant concentrated on pursuing the retreating Confederate army. Brother Bonaventure remembered that he and the Sixth Corps “marched after Lee at the double quick through swamp and woods, day and night, fighting and marching” and “did not leave the rebels time even to cook or to eat.”[7] They covered a total of 109 miles in just six days. Gaul once again praised his beloved Sixth Corps for playing a critical role in the action: “Our boys went forward like tigers, so that General Lee might not escape.” On April 9, the Army of the Potomac finally cornered the beleaguered Confederates at Appomattox Courthouse “like a shepherd dog gathers sheep.” Lee surrendered his army to Grant the same day—Palm Sunday. “It was a wonderful sight: the whole spectacle, the crying out, the hurrahs. It was worth a thousand dollars to see,” Gaul reflected.[8]

Exactly four years after the war had begun, on April 12, Gaul took the time to write Br. Ildephonse. He described the hardships of the previous two weeks, especially his diet of only coffee and hard tack. “On the last days half of us also laid down out of exhaustion. They had no sleep for eight days.” The reluctant soldier that he was, Gaul marveled at the sacrifices made by his comrades. “Certainly, it was a real Lent,” he mused.[9]

But then, Gaul looked to the future and what it might hold. “It appears we will soon be coming home,” he surmised. “The President promised it in Petersburg. […] I hope that we will see each other soon, for the war is over. Thanks be to God one million times.”[10] Two days later the president was shot at Ford’s Theatre, and the country was never the same.

After the war, the brothers returned to Saint Vincent to resume their monastic lives. Gaul settled back into the shoe shop and made his solemn vows in 1878.[11] The monk abandoned any aspirations of returning to Germany and pledged himself wholly to the Saint Vincent community. In fact, Gaul took the skills he acquired in the army hospitals and applied them in service to the college, treating sports injuries and common ailments.[12] He collected a meager pension for his service during the war and died in 1896 at the age of sixty-seven.[13]

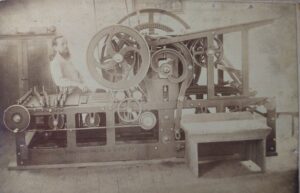

Brother Ildephonse Hoffmann and Brother Ulrich Barth both witnessed the end of the war in the Veteran Reserve Corps. Hoffmann suffered a head injury, which prompted his transfer to the Soldier’s Home in Elmira, New York. He returned home to Saint Vincent after the war and died in 1873 in the choir chapel at the early age of forty-four.[14] A hernia sidelined Barth during the war, and the Veteran Reserve Corps sent him to the Soldier’s Home in Elmira as well.[15] Barth returned to his beloved printing press at Saint Vincent and made solemn vows in 1869. He served as a mason for the abbey, as well as the Abbey of Mary Help in North Carolina, and collected a pension for his service in the war.[16] He died in 1897 at age fifty-six.[17]

History’s murky memory has largely forgotten Br. Bonaventure Gaul and his confreres, as well as their contribution to the Civil War. However, their unwilling participation in one of the great dramas of American history reflects religion’s complicated role in the Civil War.

[1] Edward S. Alexander, Dawn of Victory: Breakthrough at Petersburg, March 25 – April 2, 1865 (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2015), 9-11; Gaul to Hoffmann, March 15, 1865, ASVA.

[2] Gaul to Hoffmann, March 15, 1865, ASVA.

[3] Gaul to Hoffmann, March 15, 1865, ASVA.

[4] Gaul to Hoffmann, March 15, 1865, ASVA.

[5] During the artillery barrage the 61st Pennsylvania lost its commander, Colonel John W. Crosby, to a mortal wound, marking the nineteenth officer of the regiment to be killed in battle. See Alexander, Dawn of Victory, 63.

[6] Brother Bonaventure Gaul to Brother Ildephonse Hoffmann, April 12, 1865, translated by Father Warren D. Murrman, O.S.B., VH-41, “Letters of Civil War,” ASVA.

[7] Gaul to Hoffmann, April 12, 1865, ASVA.

[8] Gaul to Hoffmann, April 12, 1865, ASVA.

[9] Gaul to Hoffmann, April 12, 1865, ASVA.

[10] Gaul to Hoffmann, April 12, 1865, ASVA.

[11] “Gaul,” St. Vincent Journal, 38-39.

[12] “Gaul,” St. Vincent Journal, 38-39.

[13] Album Fratrum Conversorum, 43-58, ASVA.

[14] Album Fratrum Conversorum, 43-58, ASVA.

[15] Brother Ulrich Barth to Brother Ildephonse Hoffmann, January 9, 1865, translated by Father Warren D. Murrman, O.S.B., VH-41, “Letters of Civil War,” ASVA.

[16] “Brother Ulric Bart, O.S.B.”, St. Vincent Journal, Vol. VII, no. 1, September 1897, 36.

[17]Album Fratrum Conversorum, 43-58, ASVA.

Thank you for doing the exhaustive research and creating this poignant narrative of an aspect of the war valuable for insight into OSB engulfed in the terrible upheaval.

Sure thing. It’s been amazing getting to hold and read those letters!

Neat series, Evan. And I am glad that Brother Bonaventure made it home.

Thank you!

A whole new aspect of the story of the war. Thank you for this series of stories.

Thank you for your readership!

Always a joy reading your passionate historical perspectives.

Thanks, Bruce!