On the Road to Atlanta: Captured by the 46th Ohio

Rebel Colonel Daniel R. Hundley of the 31st Alabama thought his pickets were in “a very awkward and unfortunate position.” Alabama Lt. Samuel H. Sprott, a member of the neighboring 40th, recalled that “[our] rifle pits . . . were nothing but shallow holes. . . . Just behind us was a high rail fence and about two hundred yards in our rear was Noonday Creek, a good sized stream about waist deep.” To complicate matters, a small “patch of woodland . . . filled with a dense undergrowth” lay between Hundley and the 40th Alabama to his right, while beyond the creek lay another “old field” which the Rebels would have to traverse if forced to retreat. Prompted by Colonel Hundley’s warnings, both Pettus and General Stevenson visited early that morning but neither authorized a withdrawal. For the rest of the forenoon, the Rebels endured heavy artillery fire, which produced little loss but kept their heads down.[1]

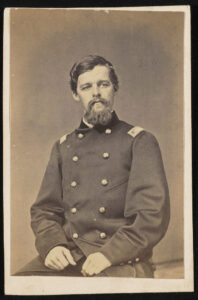

Despite his age—just 26 years—Charles Walcutt was a seasoned soldier. After graduating from the Kentucky Military Institute in 1858, he worked as a surveyor in Ohio until the war came. He raised a company in 1861 but with Ohio’s quota already exceeded, he secured an appointment as major of the 46th Ohio. He took a shoulder wound at Shiloh and, after recovering, rose to command the 46th in October 1862, and to brigade command in 1863. An innovative tactician, that spring Walcutt secured Spencer repeating rifles—which he deemed “the most complete arm of the service”—for the newly-veteranized 46th, and wrote a tactics manual for the use of the new weapons. The regiment was now about to put its repeaters to good use.[2]

Walcutt’s five regiments reported 1,488 officers and men on June 1st. The 40th Illinois numbered 280; the 103rd, 259; the 6th Iowa, 283; and the 46th Ohio, 345. The 97th Indiana counted 321 officers and men. Oliver’s brigade was 1,660 strong, while Williams’s command totaled about 1,550. A little over 4,500 Federals were about to descend on the 800 unfortunate Alabamans.[3]

“At the signal ‘Forward,’” wrote Hawkeye correspondent J. L., “the 97th Indiana moved up to within seventy-five yards of the rebel line, advancing across an open field in the face of a galling fire.” Behind them rushed the rest of the brigade, going prone “about two hundred yards” short of the enemy line. After a short reconnaissance, Walcutt renewed the charge. “As we started the boys raised a cheer,” wrote Captain Wills, “and we went down on them regular storm fashion.” 103rd Sgt. William Standard bragged to his wife that after passing through their own skirmishers, “[We] close[d] on the rebel picket who were strong in number, but we pounced on them so quickly that they did us but little damage.” J.L. noted that the Federals were partly sheltered by a “slight rise” before charging down the hill towards the Rebels and the creek beyond; moving “through an orchard and across a fence, which broke our lines considerably.”[4]

The 6th Iowa and 103rd Illinois struck Col. John H. Higley’s 40th Alabama, while the 40th Illinois and the Spencer repeaters of the 46th Ohio assaulted Colonel Hundley’s line. The 40th Alabama broke first. Watching Walcutt’s brigade bearing down upon him, followed by Colonel Oliver’s support line, Lt. Sam Sprott felt overwhelmed. “Almost before I could realize what was taking place the enemy were in the little redoubt held by Lieut. [E. H.] Ward. Seeing that prompt action was necessary, I ordered the men to fire and then take care of themselves. They rose, delivered a volley into the ranks of the enemy, not more than thirty or forty yards away, and then started across the old field in our rear.” Alabama Pvt. Grant Taylor, who was detailed to the rear that day, heard the story from a handful of survivors. “The situation that they were in rendered it almost hopeless . . . They held their ground until the enemy were close . . . and then they had to run a half mile through an old field. I suppose our boys had rather be captured than run the risk in trying to get away.” Captain E. D. Willett, commanding Company B, recorded that the “40th lost 146 men and nine officers.” Private Taylor noted that of the ”29 officers and all” present in Company G, the next day it counted only “the Capt. and 8 men, and two of them are wounded. . . . My co. is nearly all gone.”[5]

Colonel Hundley of the 31st Alabama dispatched a courier rearward and then “immediately hastened with [my] reserves to the right . . . the captain in command there having sent me word that he was being hard pressed. But before reaching him, I heard the Federal huzzaing to the charge against the left of my line, which was the weakest and most exposed.” Reversing course, Hundley and his small reserve became momentarily ensnarled in the woods bifurcating his line. He emerged from the tangled undergrowth to discover that “we were too late, the enemy having already captured the regiment [40th Alabama] on my left . . . as well as the left of my own line.” Just as Hundley ordered a retreat, a courier arrived bearing an impossible command: “To hold my position at all hazards, as General Hood intended to retake the line in front of General Stewart.” Desperate, Hundley ordered his men to counterattack: “We ran right upon the enemy, a whole brigade of them,” he noted, “cheering and huzzaing like so many devils.” With no support and “both my flanks . . . turned” Hundley soon realized the effort was folly and again fell back. Once the 31st reached the open field to their rear, Hundley admitted, “some little demoralization was manifested, and they began to scatter in confusion. . . . The Yankees dash[ed] in amongst them, shooting right and left, and bawling out to them to surrender. Sauve qui peut was now the watchword.”[6]

“The blazing muzzles of their muskets were replaced by their white handkerchiefs . . . vigorously shaken over their heads,” boasted Iowan J.L. “We did not stop long with our captures but leaving them to the care of Col. Oliver’s brigade, we pressed on . . . every man on his own hook, companies and even regiments mixing promiscuously together.” “This has been a star day,” exulted Captain Wills. “They were scared until some of them were blue, and if you ever heard begging for life it was then. Somebody yelled out, ‘let’s take the hill,’ and we left the prisoners and broke.” By this time, following “some 200 straggling sandy looking Johnnies” through the open field, Wills admitted that “we were too tired to continue the pursuit fast enough to overtake them. However, the boys shot a lot of them. . . . We took 542 prisoners” he enthused, “and killed and wounded I suppose 100.” Walcutt’s brigade lost only about “10 killed and 50 wounded.” To his wife, Lt. Col. Aden C. Cavins of the Indiana 97th exulted that “our boys went into them on the run, yelling like demons, and they broke. We took the 31st Alabama regiment, field and staff and all, and one half of a Mississippi regiment. . . . Every man in the regiment was almost scalped by the enemy’s bullets. They buzzed so close to our faces that it seemed like someone was fanning me.” Despite the intensity of that fire, Cavins recorded the 97th’s loss at “six killed and eighteen wounded,” against “capturing 640 of the rebels.” The Reverand George W. Terry of the 97th bragged that “the regiment did her work splendidly[,] having the admiration of all the generals and the troops in the rear.”[7]

[1]Hundley, Prison Echoes, 28-29; Samuel H. Sprott, with Louis R. Smith, Jr., and Andrew Quist, eds., Cush: A Civil War Memoir (Livingston, AL: 1999), 109.

[2]Warner, Generals in Blue, 535; Joseph G. Bilby, Civil War Firearms, Their Historical Background, Tactical Use and Modern Collecting and Shooting (Conshohocken, PA: 1996), 201; John C. McQueen, Spencer: The First Effective and Widely Used Repeating Rifle and its Use in the Western Theater of the Civil War (Columbus, GA: 1989), 29.

[3]15th Corps Monthly Returns, Entry 65, RG 94, NARA. The June 10th trimonthly returns were not available for Harrow’s division.

[4]J.T., “From the Fifteenth Army Corps,”; Wills, Army Life, 262; “Dear Jane,” June 17, 1864, William Standard Letters, AHC.

[5]Sprott, Cush: A Civil War Memoir, 110-11; Elbert D. Willett, History of Company B (Originally Pickens Planters) 40th Alabama Regiment Confederate States Army 1862 to 1865 (Anniston, AL: 1902), 68; Ann K. Blomquist and Robert A. Taylor, eds., This Cruel War, the Civil War Letters of Grant and Malinda Taylor 1862-1865 (Macon, GA: 2000), 259-60. istorHisHIsto

[6]Hundley, Prison Echoes, 29-31.

[7]J.T., “From the Fifteenth Army Corps,”; Wills, Army Life, 262; “June 15th,” Aden G. Cavins, War Letters of Aden G. Cavins Written to his Wife Matilda Livingston Cavins (Evansville, IN: 1906), 84; George Washington Terry Diary, KMNBP.

Which battle or skirmish was this?

Thanks for this Dave. I have 2 ancestors who fought in the 46th, only one of whom was present at Noonday Creek because the other had been badly wounded at Dallas on 27 May.

The 46th captured a disproportionate number of the prisoners taken in the campaign. This was no doubt due to its being armed with Spencers. One might have been tempted to make a run for it if your opponent had fired at you with a muzzle loader and missed. You had decent odds of getting away. But if your opponent had a Spencer, it was a “do you feel lucky? Well do you, punk?” situation and surrendering was probably the wise choice.

Does anything remain of the Noonday Creek battlefield, or has it been built over like much of the ground covered in the Atlanta Campaign?

Thanks for this, Dave. I had two relatives who served in the 46th Ohio, though only one was present at Noonday Creek: the other had been badly wounded at Dallas on 27 May.

The 46th captured a disproportionate number of the prisoners taken by Sherman’s armies in the campaign. This was no doubt due to its being armed with Spencers. One might be tempted to make a run for it when someone had taken a shot at you with a muzzle loader, or even being confronted by several who well may have emptied their weapons. When confronted by someone with a Spencer, it was a “do you feel lucky? Well do you, punk?” situation: there were good odds that your adversary had one or more left in the magazine. Surrendering was probably the wise choice.

Is there anything left of the battlefield at Noonday Creek, or has it been swallowed up by development like so much of the ground around Marietta and Atlanta?

Morning, Craig. As an Atlanta resident; I can tell you nothing is left of the battlefield @Noonday Creek; it’s a very large youth soccer field/facility now. As to Atlanta campaign sites; there’s a new state park at Rocky Face Ridge(near Dalton) that is under-stated and a nice site. Resaca Battlefield is a very poor site; signage is awful and stained with bird droppings; I-75 cuts right through the battlefield and it’s candidly just a mess. There’s a little pocket park @New Hope Church(in fact there are 5 ‘pocket parks’ mainly along US Hwy 41 from Dalton down to Kennesaw). Pickett’s Mill is an EXCELLENT site; totally unspoiled and looks like it must have looked in May 1864. It has not been encroached upon by awful real-estate developers. Kennesaw Mountain has suffered from those self-same real estate jokers(i.e, ‘Battlefield Estates’ and nonsense like that); but it’s pretty decent still and Pigeon Hill and Little Kennesaw are pretty unspoiled, IMO. Hope this helps. If Dave Powell disagrees with any of this; certainly go with his expert opinions….

Thanks, Mike. I had surmised as much based on looking at Google Earth, but I wasn’t sure exactly where the battle was–it’s not well marked on contemporary maps.

I’ve been to the sites you mention. By chance I was at Pickett’s Mill on the day it opened in the early-90s. It is a gem.

It is unfortunate that so much has been lost. Dallas (where my ancestor was wounded) is another that is pretty well gone. The most tragic loss is the Battle of Atlanta/July 22. IMHO that is one of the most remarkable battles of the war. But the freeway obliterated Bald/Leggett’s Hill. Ezra Church and Peachtree Creek also sadly lost.

Thanks again and cheers.